The photographer has spent three decades focusing her lens on such diverse subjects as the BDSM scene and Black Lives Matter. And she shows no sign of slowing down

Words by LOTTE JEFFS

Catherine Opie is late for our Zoom call, leaving me staring at myself in the screen for so long I start to wonder who it is I’m looking at. She logs on just in time to save me from a full existential meltdown. But being forced to sit awkwardly with my own image feels like the perfect primer for a conversation with photographer Opie, whose imagery has challenged the way we see and understand the world for well over 30 years.

Self-Portrait, Last Day, New York, 1985.

She apologizes and explains there’s been “a little crisis.” She has workers in her 5,000-square-foot studio near Los Angeles’ Lincoln Heights neighborhood replacing the protective film over the windows that prevents the photos she develops and prints in-house from spoiling in the heat. But they’ve run out of said material, and she’s been frantically phoning suppliers all morning. “I found someone who can deliver by 1 p.m.,” she tells me. “I’m all yours.”

Opie is notoriously hard to pigeonhole as an artist, although she claims her work is simply “about place and identity and how they inform each other.” The critics never know what to expect next, and that is part of her appeal. “I’m not interested in photography as nostalgia,” she explains when we discuss the manifesto that motivates her. “I’m interested in photography as a place of memory, as a placeholder for us throughout history.” Her 2008 Guggenheim retrospective took over four floors of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed museum in New York; her ethereal pictures of Lake Michigan hung in the Obama White House.

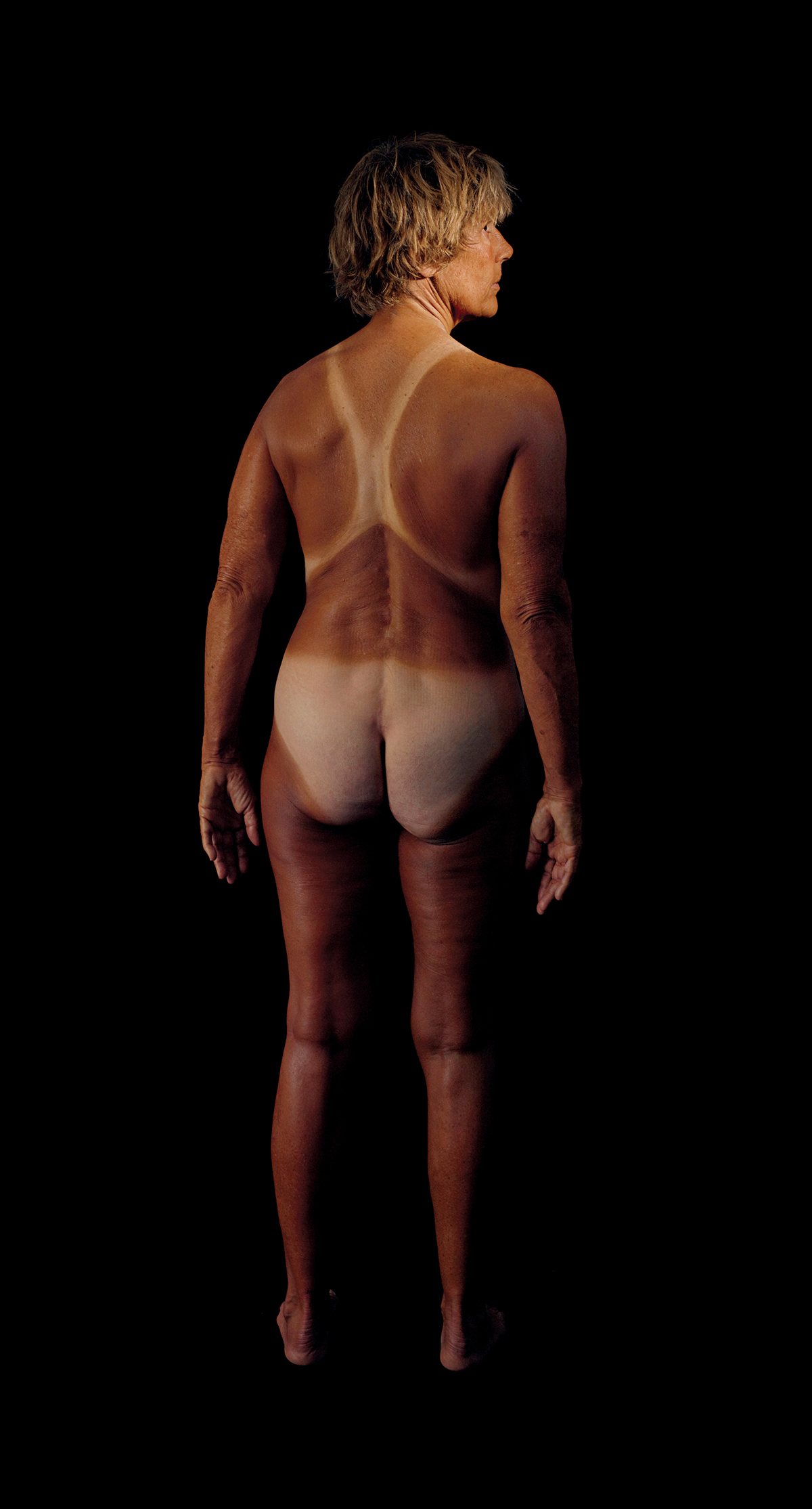

Jesse, 1995.

Early self-portraiture, most famously a 1993 shot of two female stick figures scored onto her bare, blood-dripping back, firmly established her as a “subversive.” She’s well known for her groundbreaking documentation of the BDSM and leather dyke scenes from her time living in San Francisco in the ’80s, bringing a marginalized community into the spotlight and celebrating their otherness in a way never before seen in the “establishment” art world. Today, these works continue to open a discourse for queer people, making her something of a spiritual figure in the community. “I’m even more excited by what it has done for younger queers,” she says. “I turned 60 in April, and [it’s great] to have people come up and say, ‘I saw your work in the Guggenheim and it changed my life — I was able to talk to my parents about who I was as a person.’”

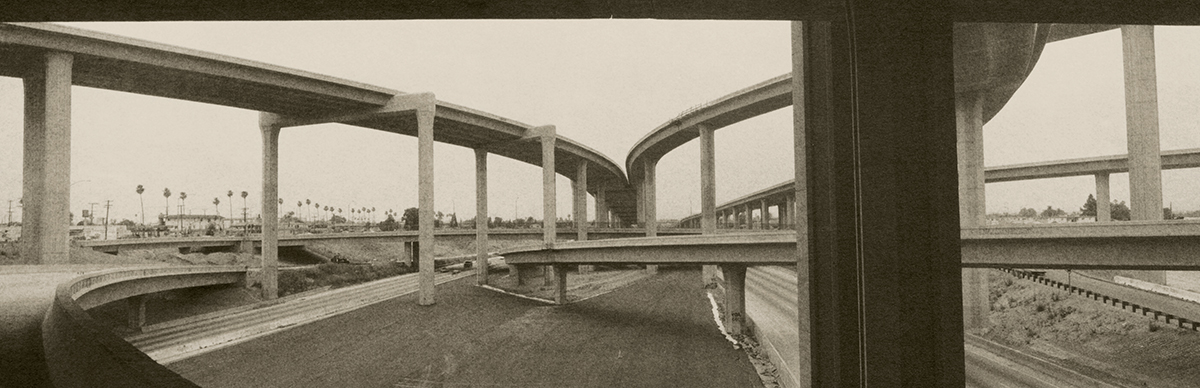

But ever since she’s subverted what it means to be a subversive, her subject matter has veered wildly, spanning freeways, queer families, disappearing swamps, football players and the personal effects of Elizabeth Taylor. Her landscapes — for example, the 2009 series Twelve Miles to the Horizon, showing the sunrise and sunset on each of the 10 days it took to cross by container ship from Busan, South Korea, to Long Beach — may not shock in the same way as some of her portraits, but both explore a sense of home, whether via community or topography.

Los Angeles Women’s March, 2017.

Indeed, there is a thread running through all Opie’s pictures, as each radically diverse subject is captured with the same depth of emotion and ability to render the familiar (a freeway interchange, a surfer, a mother) somehow strange. Now, a new Phaidon tome surveys her body of work, bringing together 300 images (including some never before seen) connected by the themes of people, place and politics, and Opie hopes that folks will finally understand that yes, this is all from the same artist.

I ask what she has learned most about the U.S. in the time that she’s spent documenting it. “How incredibly optimistic I am, and how heartbreaking this country is, time and time again.” She says she tries to make work that is not just of its time but also reflects on the historical representation of her country, and then within that, reflects the importance of community and identity. “I hope to provoke the sense of humanity, and for people to understand that difference is actually a strength.”

Untitled #3 (Freeways), 1994.

“Growing up, I felt unpopular. Photography was my little superpower”

Catherine Opie

Opie moved to Los Angeles in 1988. Over three decades, she has documented public uprisings in L.A., from the Rodney King riots of 1992 to demonstrations for immigration and labor rights in 2006 to the Women’s March of 2017. “Even though we’ve moved forward a little bit with reform, not really,” she says, referring to the nation as a whole. “I mean, women who are sleeping, who haven’t done anything wrong, can have police barge into their home and shoot them, like Breonna Taylor.” During last summer’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations, she avoided the familiar forlorn mask-on-the-street shots in favor of reflecting “where we are in this time of COVID and racial injustice without actually creating more cliches around it.”

During the pandemic, Opie and her wife, Julie Burleigh — a painter and garden designer — sent their son, Oliver, off to college at Tulane University in New Orleans. After no prom to speak of, his high school graduation was held in the backyard of their home in Wilshire Park, near Koreatown, replete with cap and gown and their dog, cat, lizard, two rabbits and chickens looking on. “There was never a time in my life that I didn’t want to have children,” Opie tells me. “It was a question of if financially I would be able to do it. So as soon as I got my teaching job at Yale with health insurance, I was like, ‘Okay, I’m 40, I have a full-time position. I’m getting pregnant.’”

Diana, 2012.

When she met Opie, Burleigh was a single mom to her daughter, Sara, whom she had had at the age of 18. She was head of the painting department at Washington University in St. Louis and Opie came in as a guest artist for one year. They decided to make a life together. “And Julie thought at 40, maybe I wouldn’t get pregnant because she had literally just finished raising Sara.” She says that for Julie this past year has been “really monumental, because it’s the first time in her adult life she’s not raising a child.”

As a hugely successful artist (reportedly able to earn over one million dollars in a good year), it would have been really hard to have a child without the support of her wife, Opie explains. “[Julie] really did pick up the slack when I was constantly traveling. But we always had a rule that I wasn’t allowed to be gone more than 10 days.” At the time of Oliver’s birth in 2001, same-sex couples could not legally marry under California state law, meaning Julie couldn’t be named on the birth certificate. “We always talked about me adopting Sara, and her adopting Oliver, but it was just a lot of legal fees and paperwork. And we felt like no, we are a family.” Sara now has a 7-year-old son and also lives in L.A., meaning her moms can dote on their first grandchild.

Betsy & Olivia, Bayside, New York, 1998.

Opie’s close friends, many of whom were part of queer subcultures in California in the ’80s and ’90s, are often the subjects of her portraits. She shot them against bold colored backdrops to evoke the paintings of Hans Holbein, offering a sense of reverence to a marginalized community. I ask how capturing the personalities of strangers differs from working with close friends. “I don’t have any preconceived ideas of who they are, as a person. There is a different ebb and flow — one is bearing witness, and one is recognizing this very internal relationship of either friendship or somebody who I completely admire, such as David Hockney.”

It was the work of photographer Lewis Hine that first inspired Opie. Born in Sandusky, Ohio, she received a Kodak Instamatic camera from her parents for her ninth birthday, and she began shooting her family and neighborhood. “Growing up, I felt displaced always,” she says, “and unpopular. Photography was a way that allowed me to make friends and have something really special that I could give out to the world. It’s like my little superpower. I spent all night in the darkroom so I could go back to school the next day with a stack of prints.” She wasn’t out at school: “I was really trying to think about having a boyfriend, but fortunately I got to ’Cisco soon enough to realize that I didn’t need one!”

Cobalt Blue Sky, 2015.

Opie is such a fixture on L.A.’s art scene — sitting on boards at MOCA and the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts — that it’s been reported her friends refer to her as the mayor of the city. I ask if it is easier to challenge the establishment from inside it. “I think it is better to be both inside and outside,” she answers. “I like to stand over the doorstep. I really value what I’ve learned being on several boards as an artist, because it’s not a room that you actually usually get to sit in.”

She is optimistic that the L.A. art scene will thrive again post-COVID, especially as institutions address their own internal struggles with inclusivity and diversity. “Recently we’ve watched curators lose their jobs, we’ve watched museum directors step down. I think that there’s a lot of questions right now in play about who are the museums for and what do they collect? There’s a really interesting reckoning with that.”

Untitled #3 (Inauguration Portrait), 2009.

After a year at home, this summer Opie plans to get back on the road, spending six weeks alone in Rome “thinking about the Vatican and what it means for an isolated city within a city that has a different kind of governance — the boundaries and the spaces of that.” Closer to home, her priorities are shifting, and she is less focused on documenting emergent subcultures as on using her art and influence to give back to the city’s lower-income communities, volunteering in schools and helping children in South and East L.A. with their college essays. And there’s still a whole year left to mount that mayoral campaign, should she so wish.

Catherine Opie (Phaidon, $150), with essays by Hilton Als, Elizabeth A. T. Smith, Douglas Fogle, Helen Molesworth, and Catherine Opie in conversation with Charlotte Cotton, is now out.

Feature image: Gina & April, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1998.

All images courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong/Seoul/London; Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples; and Peder Lund, Oslo.

This story originally appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.