The world’s leading cultural institution focused on film is opening this month on L.A.’s Museum Row. C Magazine takes an exclusive first look

Words by STEPHANIE RAFANELLI

Photography by KURT ISWARIENKO

Hollywood was founded by mavericks, visionaries and progressives. And yet, despite a prolific artistic output that has shaped our global psyche for over a century, somehow, at some point, almost 100 years after The Jazz Singer launched the talkies with the words “You ain’t heard nothing yet,” it had seemed that Hollywood had stopped listening. With an Academy Awards tradition that at times felt out of step with our age, it was criticized for being socially well-intentioned but intellectually slight and too white. But 2021 will go down in cinematic history as the year Hollywood woke up.

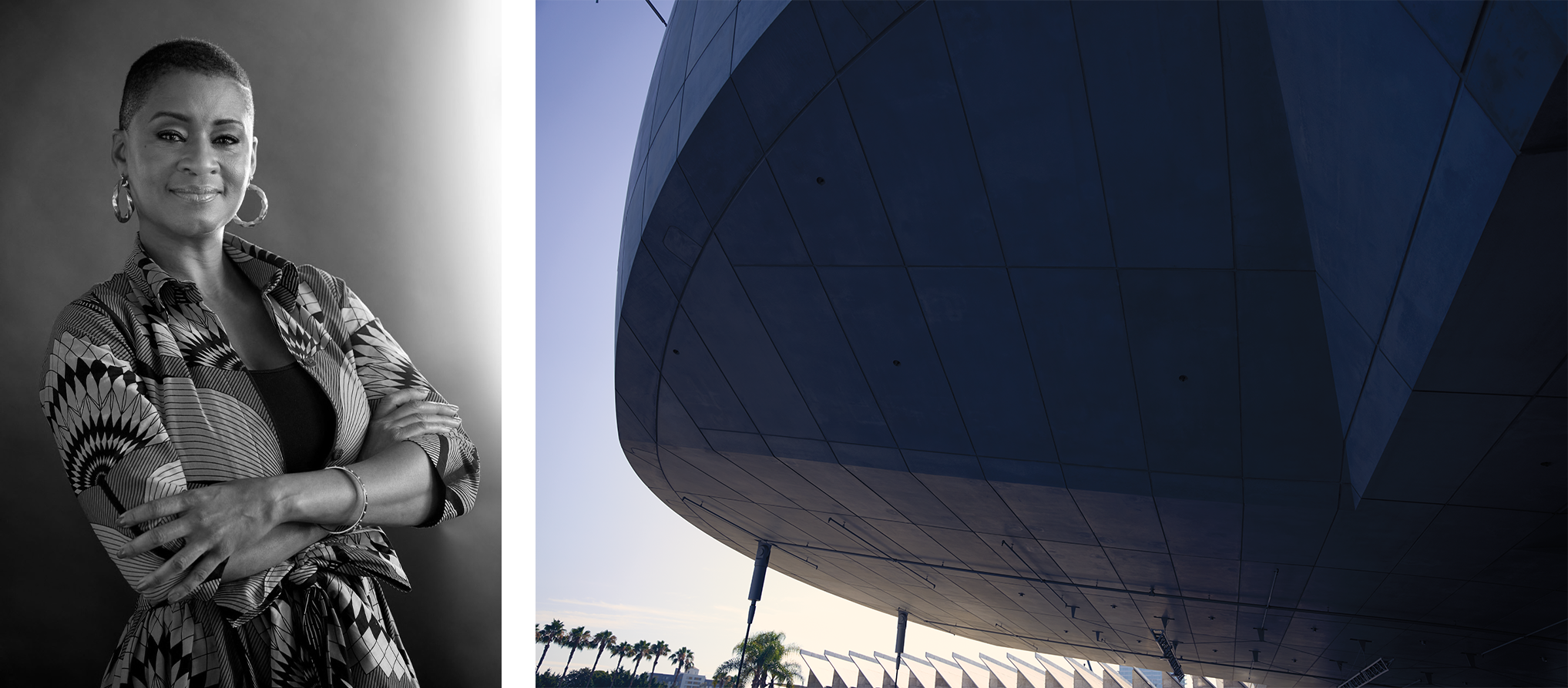

The sphere, which houses the 1,000-seat David Gefffen Theater, has a terrace with sweeping views of the Hollywood Hills.

This watershed moment is manifested in a monolithic symbol in bricks and mortar: the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures along Miracle Mile, near LACMA, reaffirms Hollywood filmmaking as a high art again. After years of delays, AMMP — the largest center in the nation dedicated to the history, science, cultural impact and preservation of filmmaking and the sheer wonder of cinema — is opening in the former May Company building, one of the city’s best examples of Streamline Moderne architecture. The original structure was designed by Albert C. Martin Sr. (who also did Los Angeles City Hall), but the museum comes with an addition by highbrow, high-tech Italian architect Renzo Piano, who is renowned for creating the impression of architectural weightlessness: a 1,000-seat spherical theater with a domed terrace framing views of the Hollywood Hills. Piano’s 45,000-square-foot glass-and-concrete sphere seems to float next to the historic structure like a vision from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, a giant architectural eye looking at once to the past and the future.

The original building dates to 1939, which coincidentally is often held to be the greatest year in Hollywood for its prolific 365-film output, including the Technicolor epics The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind. “There’s a lot of symbolism in the building,” agrees museum director and president Bill Kramer, who came on board in 2012 (the same year as Piano) and began fundraising for the museum after Academy CEO Dawn Hudson put her weight behind the project. Renovations were meticulously overseen by preservation specialist John Fidler, who replaced one-third of the 350,000 gold-leaf mosaic tiles — with new ones from the original Venetian manufacturer, Orsoni — on the illuminated cylindrical structure that faces the intersection of Fairfax and Wilshire, like a stack of gilded film canisters. “We want our museum to be the [new] center of Hollywood,” Kramer clearly sets out. “And perhaps bring a little glamour back to the notion of moviemaking again.”

Two glass-and-steel pedestrian bridges — named for BARBRA STREISAND and CASEY WASSERMAN — connect the historic 1939 Saban Building with the grand addition.

Along with a return to rarity and mystique is a hefty dose of gravitas. Our era’s laser focus on the illusory notion of celebrity has been displaced by a levelheaded emphasis on craft through industry key players across 17 branches of the Academy, from writers and editors to producers and costume designers, all of whom have set up task forces to advise on relevant exhibitions, attracting both museum and industry heavyweight scholars alike. Former Walt Disney Company CEO Bob Iger, Tom Hanks and Annette Bening chaired the initial campaign, raising $388 million for the museum from donors including Barbra Streisand and Steven Spielberg (the Spielberg Family Gallery will be showcased in the museum lobby). Laura Dern, Ryan Murphy, Emma Thomas and Eva Longoria all sit on a diverse board of trustees chaired by Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos.

“All of these people care deeply about the museum,” Kramer stresses. “And having Renzo onboard in the early stages of conceptualizing the project also showed members that we were looking at the history of film with an eye on creating spaces that were as thrilling as sitting in a theater watching a movie.” For this, Kulapat Yantrasast’s wHY architecture, also responsible for the Marciano Art Foundation, was brought on to design immersive and experimental experiences in exhibition spaces.

But by far the most powerful commitment is the new Inclusion Advisory Committee, chaired by producer Effie Brown (Dear White People, Real Women Have Curves) in a public statement of recognition by the Academy. “The film industry, like many of the systems that have been created over the last few centuries, has been racist, oppressive, sexist and homophobic in moments,” Kramer admits. “We have to face our past head-on.”

“We want our museum to bring a little glamour back to movie-making again”

BILL KRAMER

Academy Museum of Motion Pictures director and president BILL KRAMER stands inside the 288-seat Ted Mann Theater.

Critical to this candid conversation has been the recent appointment of Jacqueline Stewart as chief artistic and programming officer. One of the country’s foremost film scholars and a senior fellow of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, she is also a three-term appointee to the National Film Preservation Board, who has led reports on diversity, equity and inclusion for the National Film Registry. “The Academy has been listening,” she affirms. To prove it, they have even boldly issued a mea culpa. “There’s a welcome text that visitors receive when they arrive, setting out our mission statement: that while we are celebrating the arts and sciences of cinema, we are also fully recognizing the damage that movies have done in terms of supporting social inequities and philosophies of difference,” Stewart says.

The main exhibition strand, “Stories of Cinema,” constitutes an inclusive retelling of international film history through “a multiplicity” of viewpoints, as Kramer puts it. “The history of cinema traditionally covered filmmakers like Orson Welles,” Stewart continues. “And in our opening of ‘Stories of Cinema,’ Citizen Kane is right there at the front. But alongside it is another vignette on pioneering early African American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux [1884-1951]. The Academy Museum is an institution that now makes it impossible to not acknowledge people who worked in parallel cinema to Hollywood, to whom the doors have been closed all this time.” Indeed, the opening series includes spaces dedicated to and co-curated by Pedro Almodóvar (an auteur of the Movida Madrileña, a hedonistic counterculture that emerged after the death of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco) and Spike Lee.

“Here we have an iconoclastic and independent voice, who has had some touch points with the Academy [Lee won an Oscar for BlacKkKlansman in 2018] but whose success has been in no way defined by it,” Stewart says. “In 1990, when Driving Miss Daisy won the Best Picture Academy Award [instead of] Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee launched a pretty extensive campaign against the Oscars: ‘We was robbed’ was the tagline. So it’s extraordinary that he’s collaborated with us.” Here he showcases his collection of movie posters and memorabilia telling the story of his directorial influences, from Jim Jarmusch to Akira Kurosawa. “You get to understand how his Malcolm X is an epic on the scale of Spartacus.” Bruce Lee’s cultural contribution is also reappraised: “Bruce Lee was a philosopher, a choreographer, an auteur…”

From left: Chief artistic and programming officer Jacqueline Stewart. The exterior of the newly constructed Sphere building.

Along with a gallery devoted to The Wizard of Oz, the museum opens with the first North American retrospective dedicated to animator Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle), whose strong animated female protagonists are, in some ways, alter egos of Dorothy Gale. Extensive exhibitions are also dedicated to every aspect of filmmaking: Cinematography, for example, ranges from the three-strip Technicolor camera used to film The Wizard of Oz to one of the iPhone 5Ss that Sean Baker used to shoot 2015’s Tangerine, a movie about transgender sex workers. In addition to the Academy’s vast archive of screenplays, films and production art, the museum has acquired more than 8,000 objects, which are on display alongside over 1,000 pieces from the private collections of film icons such as Alfred Hitchcock, Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn.

The Academy has also tapped its pool of talent to collaborate on limited editions to be sold through the museum, alongside vinyl, books and collectibles: Standouts include Modernica x Studio Ghibli chairs inspired by Miyazaki’s films, and a capsule collection by stylist and costume designer Arianne Phillips. Meanwhile, Fanny’s restaurant, named after vaudeville star Fanny Brice (donor Wendy Stark’s grandmother, who was played by Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl), is being run by Bestia’s Bill Chait and Wolfgang Puck’s catering operation. It’s all a far cry from Planet Hollywood.

But this haute celebration of Hollywood doesn’t preclude a dose of social realism. The Impact Reflection gallery focuses on activism and film through climate change, Black Lives Matter, labor relations and the Me Too movement — “a recognition,” Stewart calls it, “that this is something that the industry has been struggling with addressing.” Will any Weinstein Company films feature in the museum? “I don’t think anyone has been canceled,” she notes. “It’s not about taking things out, but being prepared to have the difficult conversations that are essential for a civil society.”

Next up will be “Regeneration: Black Cinema from 1898 to 1971,” the most comprehensive survey of the field ever mounted, showcasing newly unearthed early Black films. Stewart explains, “It gives the fuller stories of so many Black film artists. We recognize Hattie McDaniel in our Academy Awards History gallery, but in ‘Regeneration’ we get a much deeper sense of her significance in the African American community.” Paying tribute to the forgotten can be moving work. “Evelyn Preer was a well-known Black stage actress who starred in Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates in 1920.” Stewart’s voice wavers. “Just seeing her on the Academy wall, knowing that millions of people are going to see her face — a kind of recognition that she never could have imagined for herself — I feel especially proud.”

Julianne Moore wears LOEWE coat and BULGARI and CARTIER jewelry.

Stylist assistants SARAH NEARIS and ELLIOT SORIANO.

Makeup for Ruth Negga by MELANIE INGLESSIS at FORWARD ARTISTS using ARMANI BEAUTY.

Hair for Andie MacDowell by JOHN D at FORWARD ARTISTS using ORIBE.

Makeup for MacDowell by PATI DUBROFF at FORWARD ARTISTS.

Nails for Negga and MacDowell by MARLA BOLDEN at OPUS BEAUTY using CHANEL Le VERNIS.

Hair for Édgar Ramírez by SASCHA BREUER at THE WALL GROUP using WELLA.

Feature image: Édgar Ramírez wears DSQUARED2 tuxedo, $2,565. PRADA shirt, $805. DIOR MEN shoes, $1,050. Andie MacDowell wears PRADA coat, price upon request, turtleneck, $1,150, pants, $1,430, and shoes, price upon request. Ruth Negga wears ETRO dress and belt, $7,520 (sold as set). JIMMY CHOO pumps, $725. GRACE LEE rings, from $2,880.

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of C Magazine.