The artist looks back on 10 years of creating disquieting images

Words by ELIZABETH KHURI CHANDLER

Photography by DYLAN COULTER

Styling by ALISON EDMOND

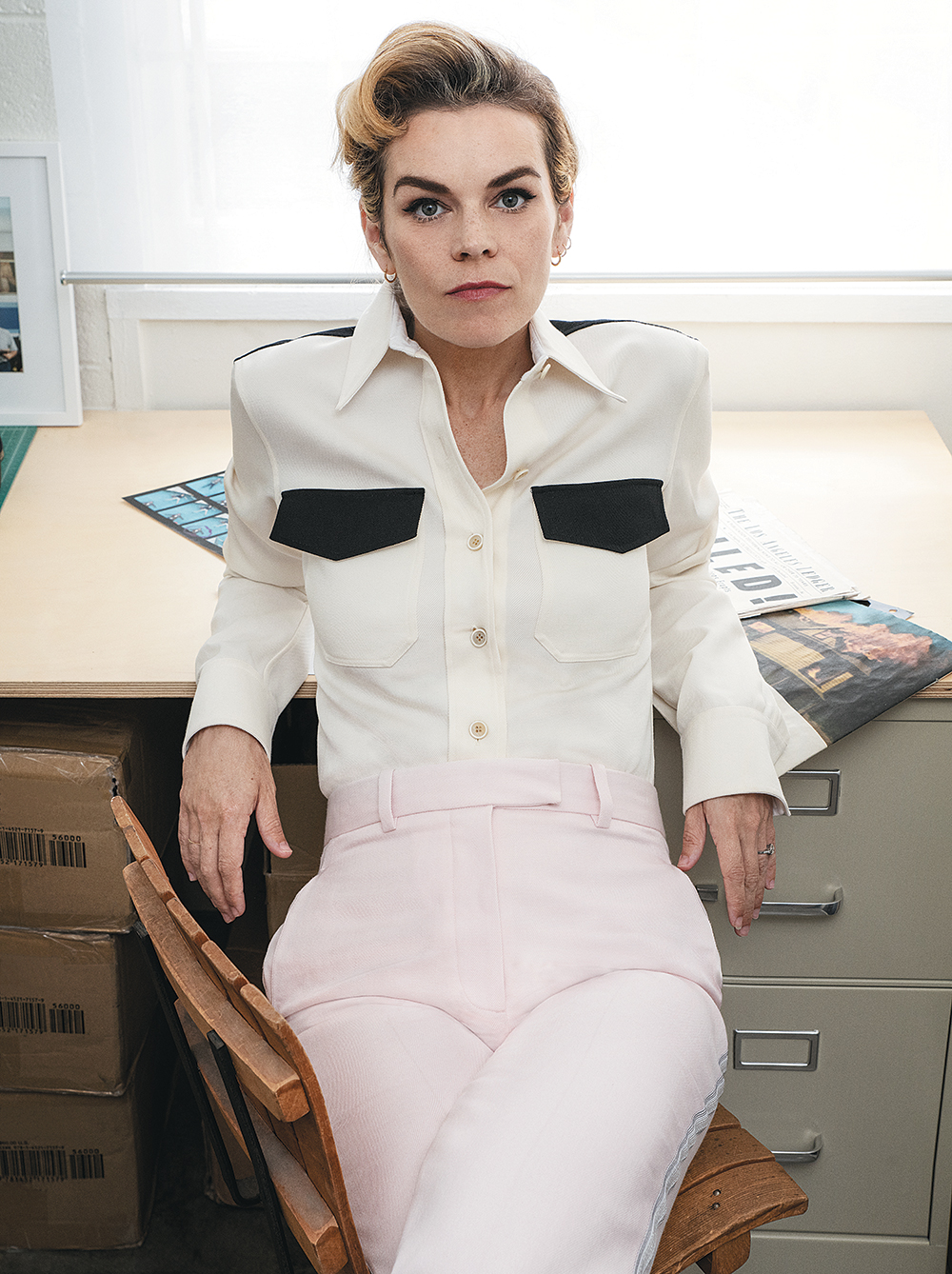

It’s an unrelentingly hot summer’s day on a busy street in East Los Angeles, and the aproned makeup artist, the tattooed hairstylist and the photo team hauling their bulky reflectors are all beginning to wilt. But not Alex Prager. Petite and smiling, bouncing from pose to pose, strategically draping a coat over a pole in the shot to add texture to the composition, the artist is unruffled, cool and fresh—a total pro. She isn’t usually the model, of course. Prager is famous for her work behind the viewfinder.

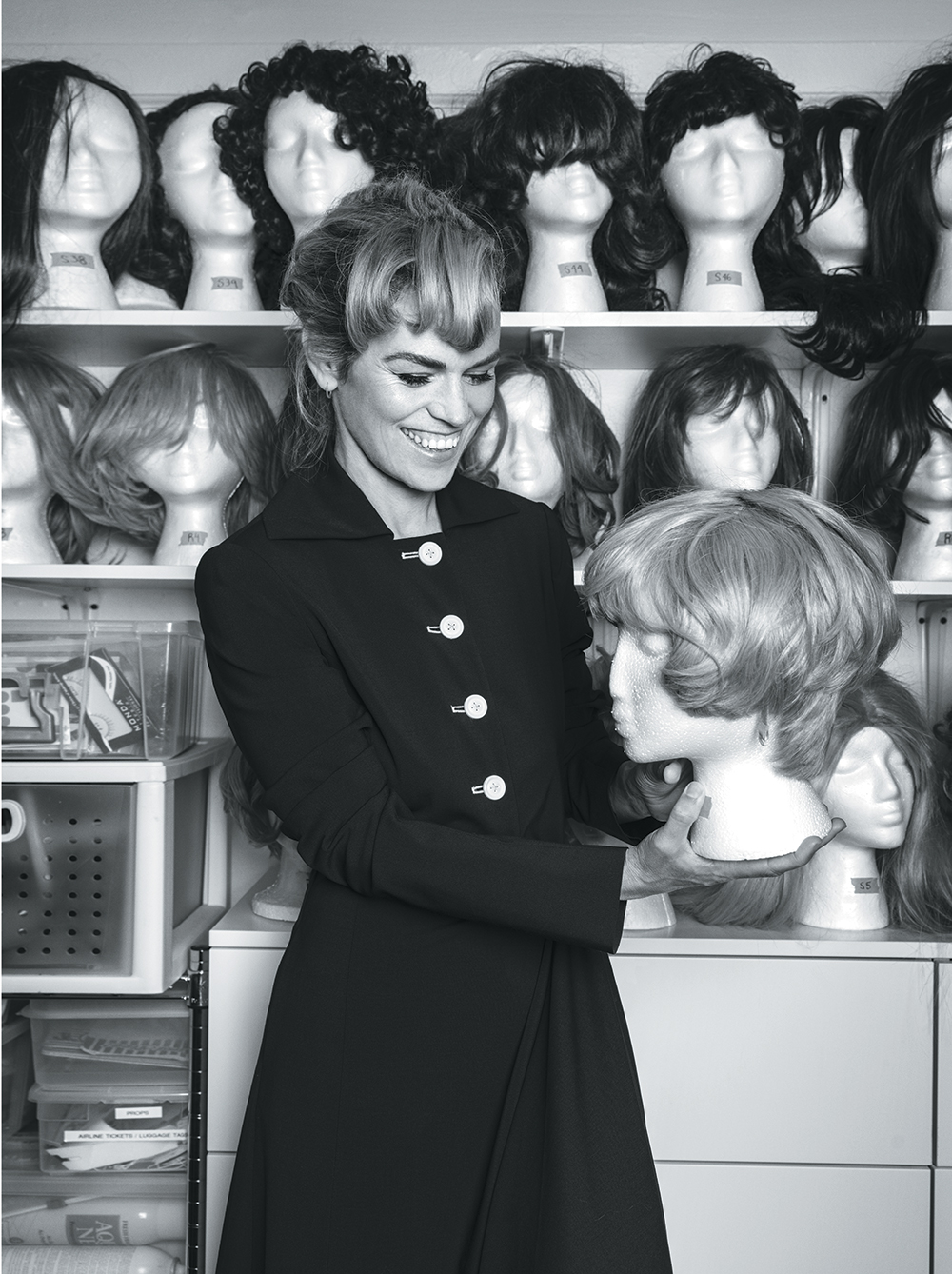

Shot completed, we traipse back to her studio in Silver Lake, a simple four-room affair sparsely decorated with a few Persian rugs on the floors, a modern sofa and tables, and prints from her many exhibitions on the walls. It seems like a minimalist retreat, but then you walk into the prop room stuffed to the gills with wigs in every color, dresses, mustaches and a baby doll—everything necessary to set a scene.

The hyperdetailed photographer and filmmaker—a longtime darling of the contemporary art and fashion worlds—is having another major moment. She’s the subject of a midcareer retrospective at The Photographer’s Gallery in London; she has an upcoming exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts Le Locle in Switzerland in November; and her accompanying new book, Silver Lake Drive (Chronicle Books), is due out in October in the U.S. Prager’s work has a strong sense of place, and she is known for a complexity and dissonance that suits the title. “It’s such a weird, unreliable, beautiful, magical and disgusting city that has all kinds of artifacts and all these layers of beauty and lies and promise and perfection,” she says of Los Angeles, her hometown.

Nearly 10 years ago, the self-taught artist, who grew up in Los Feliz and decided to become a photographer after going to a William Eggleston exhibition at the Getty, burst onto the scene with her provocative photographs of women, strategically posed and highly done up: slurping a Big Gulp; being launched through the air from an explosion; or caught in telephone wires, like a spider, helpless in a web. Now represented by Lehmann Maupin, Prager’s films and large-scale photographs often give the impression of sweetness and glamour, only to turn slightly sour as the viewer’s gaze lingers. That unsettling feeling has earned her references to visual greats Alfred Hitchcock, Diane Arbus and Enrique Metinides; parts in exhibitions at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna; solo shows at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and Foam Fotografiemuseum in Amsterdam; and awards such as the London Photographic Award.

The work has a retro feel that she infuses quite deliberately. “Nostalgia is a great tool to throw into the mix, because it gives people a feeling of safety,” Prager explains, citing the films of Hollywood’s Golden Age as influential. “The film industry speaks of darker subject matters, but colored with nostalgia and delight—and you think you’re just looking at a pretty picture. But there [are] all different kinds of things underneath that aren’t necessarily comfortable to look at, or very pretty or fun.”

Over the years, Prager’s sophisticated play with desire and angst has proliferated and iterated, progressing from single-subject compositions to tableaux-like photographs of meticulously arranged crowds, commercial work, and short films percussed with music, often featuring big-name stars—Brad Pitt as a mad man, or Jessica Chastain as a glamour-puss, smoldering into the lens. “I never said, ‘I’m going to be a filmmaker,’” says Prager of her organic transition to film. “In Touch of Evil, the actors made me into a director by asking me what the backstory was, and suddenly I started thinking of narrative in a more linear form.” Her film work has been equally successful as her photography: Prager’s shorts for The New York Times won an Emmy, and her film Applause was looped on screens in Times Square in June 2017.

Her most recent film, La Grande Sortie, whose still photographs close the book, was performed by two dancers from the Paris Opera Ballet and set to a Stravinsky score adapted by Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich.

Classical dance appealed to Prager right away; she counts The Red Shoes as one of her favorite films. “From far away, ballet looks like the most beautiful fantasy you’ve ever seen. But then you see the makeup up close when you’re finished with the performance, with all the sweat coming through—it’s got a horror film aspect to it.”

In La Grande Sortie, the female dancer begins to interact with her audience and embarks on a tortured mental roller coaster that ends with a narrative mic drop. For Prager, it was not only an opportunity to explore “the ugly underbelly coming together” of that world, but also to dive into the mental pressure on artists, expected to be so public and no longer just speak through their work.

“For me personally, La Grande Sortie had a lot to do with me confronting an audience,” she says. “How you can become your audience when you’re up on a stage, or when you’re doing anything where you feel vulnerable. Your reality can be warped by whatever state your mind is in.”

Silver Lake Drive may mark the end of 10 years of one thought, but she’s already moving on. “I like to come up with an idea that I’m really into and I feel like it challenges me, terrifies me. If I’m not a little bit scared, then I’m just coasting,” she says. You can feel that she’s on the brink of something bigger, moving forward purely by instinct, like a woman grappling in the dark. So then what’s next?

She plays it coy. “I’ve already started it,” she says.

Hair by PAUL RIZZO.

Makeup by HOMA SAFAR.

This story originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of C magazine.