On the eve of his LACMA exhibition, David Hockney welcomed 40-some of his sitters of the past 50 years at a reunion

Words by PETER DAVIS

Group portrait by CATHERINE OPIE

Photography by RAINER HOSCH

David Hockney has a large, sweeping circle of close friends. And from July 2013 through March 2016, he painted portraits of 82 of his most intimate pals, family members and acquaintances, including longtime studio manager J-P Gonçalves de Lima; art world luminaries Larry Gagosian, Irving Blum and Douglas Baxter; Frank Gehry; his youngest brother, John Hockney; fashion designer Celia Birtwell; photographer Ray Charles White; conceptual artist John Baldessari; his housekeeper Patricia Choxon; and 13-year-old Rufus Hale (the son of artists Tacita Dean and Matthew Hale), who was just 11 when he sat for the artist.

Although Hockney once proclaimed, “I don’t value prizes of any sort,” he has won countless awards (in 2003, he received the prestigious Lorenzo il Magnifico Lifetime Achievement Award of the Florence Biennale). Yet when offered a knighthood in 1990, he declined the recognition. Charmingly modest, Hockney is considered by many to be the greatest living artist today. “Hockney is so famous, so popular, such a great talker and character that it’s easy to take him for granted as an artist,” Jonathan Jones, the art critic of The Guardian, once said. “He is one of only a handful of 20th-century British artists who added anything to the image bank of the world’s imagination.”

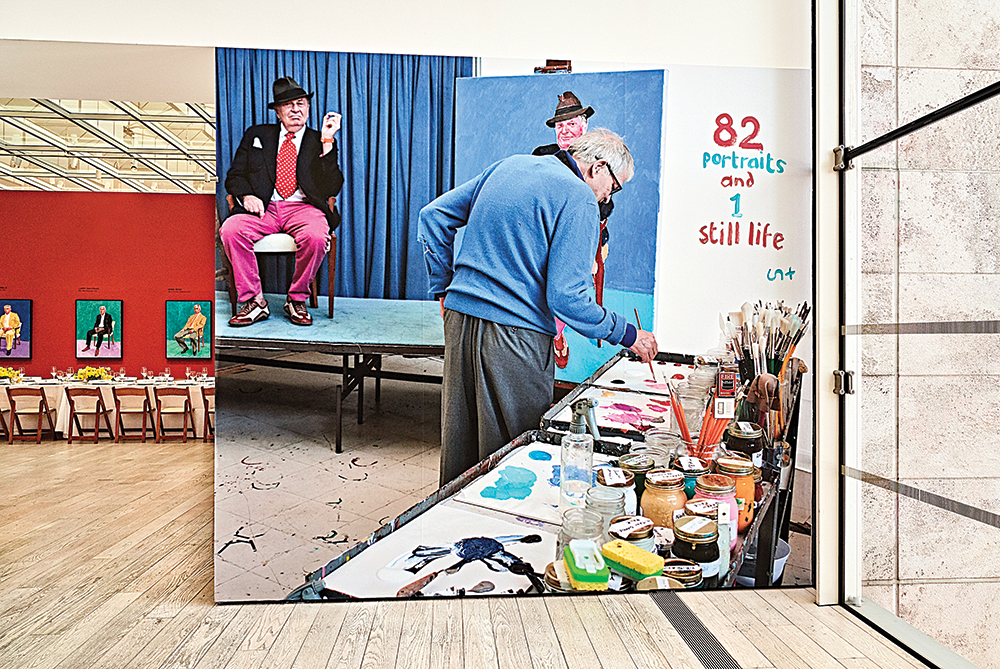

All 82 sitters arrived at Hockney’s studio, and all posed in the same chair on the same platform with the same blue curtain behind them. The portraits—each strikingly distinct thanks to the organic emotion captured from each subject through gaze and body language—are hung in chronological order in two light-filled spaces at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The massive “82 Portraits and 1 Still-life” exhibition is ultimately viewed as elements that comprise one extraordinary body of work: a truly up-close, personal look at Hockney’s innermost circle. The portraits (and one still life), all acrylic on canvas, originated at the Royal Academy of Arts in London before traveling to: Venice, Italy; Bilbao, Spain; Melbourne, Australia; and finally Los Angeles, the city Hockney has lovingly called home for more than three decades.

Why 82 portraits? It was quite simply the number of canvases that fit perfectly in the Royal Academy of Arts. Well, to be specific, one person didn’t make the final cut. “If you don’t get it the first day, you’re not going to get it,” Hockney explains while sitting among his work at LACMA. He refuses to name who got eighty-sixed. “He wasn’t looking at me, so that’s why I left him out, but I did paint his daughter.” Forever stylish and easily recognizable, Hockney is sporting his trademark round spectacles, a custom-made bright blue and pink striped Hermès cardigan, khakis with paint splatters, and a blue case holding his iPhone, slung loosely around his neck, with “Tel.” scrawled across the front in white. He’s gentle, but mischievous—smiling and laughing frequently. He sits languidly—a little slouched like a teenager. And his voice is soft with a slight gravel.

“When I had done about 60, I realized, well, this is going to be an important piece of work,” Hockney says.

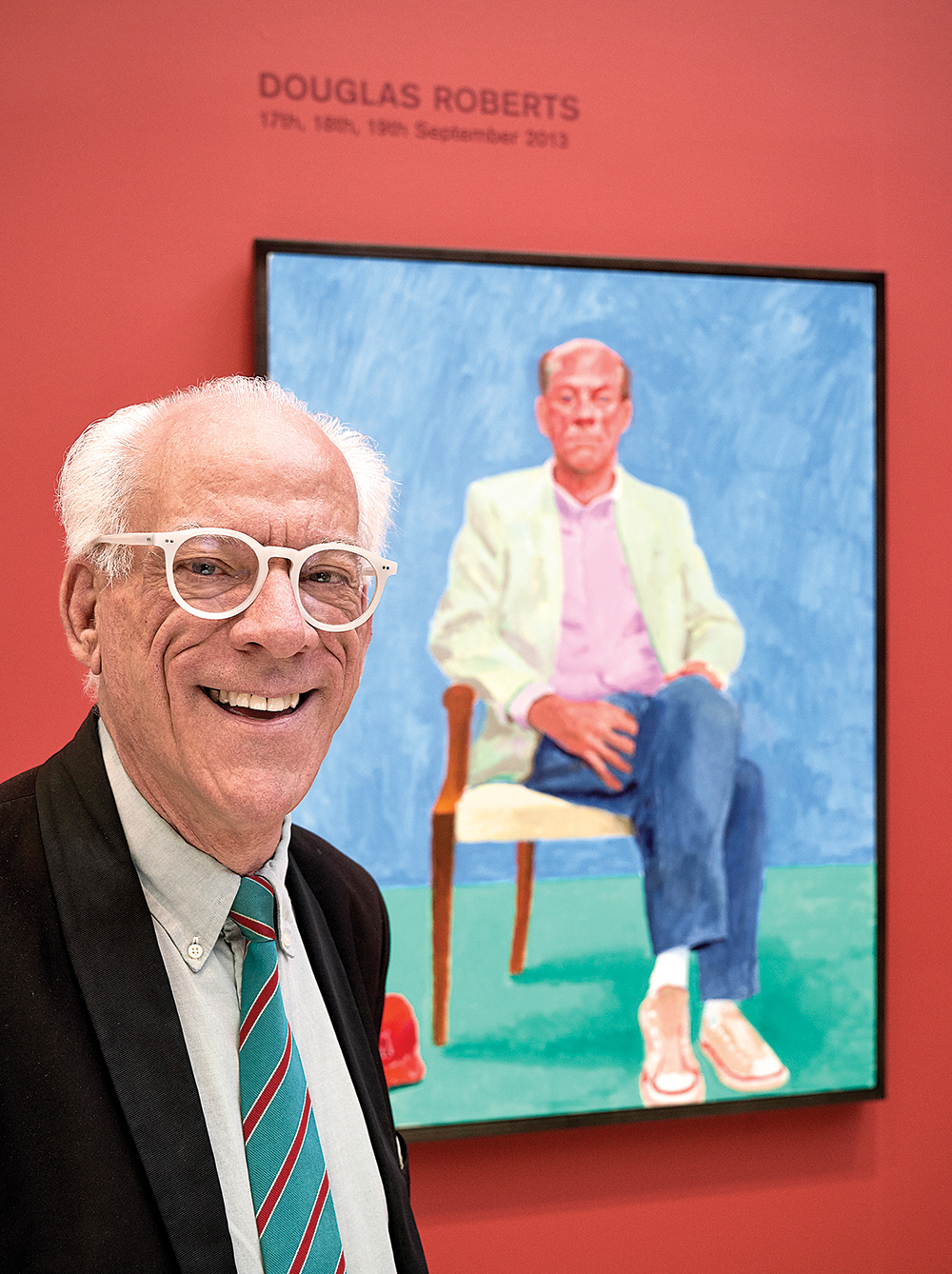

Each portrait took two to three days to complete. Sitters arrived at his studio at 9:30 a.m. sharp and held their pose for three hours while Hockney sketched in charcoal the first day to outline what he wanted to capture. Then there was a lunch break—and for Hockney a chance to smoke cigarettes (he still chain-smokes Camels and, during a private lunch for the sitters, insisted on a table outside the exhibition building that had an ashtray and a sign that commanded: “Reserved for Mr. Hockney”). The afternoon was another three-hour session. “I was very jet-lagged. I kept nodding off,” admits Pace Gallery president Douglas Baxter, who first met Hockney in Los Angeles around the early ’80s. “And at the end, David said, ‘I didn’t really get you.’ I remember looking at it together on the third day when he was done. I was standing there and he took out a canvas and did a quick, kind of oil sketch of me with my arms akimbo, looking at my portrait. It’s a fabulous thing—very spontaneous, very free.” Baxter pauses, then sighs. “Unfortunately, he didn’t give it to me.”

Peter Goulds, Hockney’s art dealer for 40 years and the founder of L.A. Louver gallery in Venice, notes that Hockney is completely silent while working. “He doesn’t talk. Your exchange is in the pauses during cigarettes. I was very relaxed those three days. I’m pleased with it. My mother didn’t like it. She said, ‘You don’t have pouting lips.’” As Goulds’ eyes darted around the gallery at LACMA, the early afternoon California sun infusing a sun-kissed glow, he noticed: “The light here is very much like the top light in his studio. These paintings are being seen in a way that is corresponding to the way they were made—startlingly so, in that sense. This has this generosity of light. The beauty is how far they read across the room.”

Methodical and precise in his approach to each session, Hockney had only one cancellation. “My father had just died,” recalls Ayn Grinstein, a close confidante of Hockney and the daughter of Gemini G.E.L. co-founders Elyse and Stanley Grinstein. “I ended up doing the portrait three days after my father’s funeral, which David went to.” While most of the portraits capture the joyfulness of the sitters, Grinstein’s grief over the loss of her father can be sensed in her somber, far-off eyes and the slight slump of her pose. “She just came another day,” Hockney says of Grinstein. “I thought I might as well do something else, so I just got some fruit and put it on the [bench] and painted it.” Hence, the one still life in the show.

Blum, a legendary art dealer who met Hockney in the ’60s, remembers his session as if it were yesterday. “It was absolutely wonderful,” he gushes. “I thought the experience was completely brilliant. You go up to the studio and you don’t say anything, and then around 12:30 you break for lunch. He’s completely enchanting, telling funny stories, talking about the old days. And then you go back to the studio and he doesn’t say a word. I loved being with him.” Sounding more like a 30-something art world insider than a 13-year-old, Hale recounts, “It was 10 days after my 11th birthday. It was the first time I’d ever sat for a portrait. I knew it was a big deal. I kept still. It was still a challenge for an 11-year-old not to move about. The way he paints is: He doesn’t speak, and then he stands back and looks at his work. I was mostly thinking how important this was going to be. I didn’t grasp the full magnitude of it all, but I knew it was rather important.”

Hockney’s immense body of work—from brightly colored landscapes to his iconic pool paintings to his intimate photographs and compelling portraits—is closely associated with Los Angeles, the city of which he once said: “In my old age, I’ll be in L.A.” “I’ve always preferred L.A. to New York,” Hockney confesses with a whisper and a boyish smile. “New York goes that way [he throws his long arms upward toward the sky] and L.A. goes this way [he shoots his arms from left to right]. It’s nicer here. It’s greener. I first came here 50 years ago. It is home.” Hockney grew up in Bradford, an industrial city in the north of England. He ventured to California and instantly fell in love with Los Angeles. “California is always in my mind,” he once said. Baxter muses: “I think probably there was something about his being gay that made California in the ’60s seem like the place to be—the sense of freedom, the lack of a defined social or class structure.” No artist has rendered the light, the laid-back mood and the zeitgeist of Los Angeles in the way that Hockney has. “He really saw the place,” elaborates Blum. “He saw the various eccentricities of the place and the identifying features of the place—and he captured it all. No one really has in as great a way.”

As Hockney approaches his 81st birthday, with both a massive, roving sold-out retrospective that just closed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the new portrait series at LACMA, he shows no signs of slowing down. Unlike many artists who turn their backs on and noses up at modern technology, Hockney boldly embraces it, creating portraits on his iPad and constantly exploring new ways to make images. “This is old work as far as David is concerned,” laughs Stephanie Barron, LACMA’s senior curator and department head of modern art, of the show. Outside the exhibit on a bridge is a 25-foot-long photomural titled In The Studio, December 2017, in which Hockney intricately investigates reverse perspective. It took 3,000 photographs of his studio (in which Hockney stands in the middle, surrounded by his paintings) and a cutting-edge photogrammetric computer software program to compose the three-dimensional scene. The shadows were added digitally. “It is a photograph that makes us rethink photography,” Barron declares.

This constant curiosity and obsession with photography and gadgetry is not only what keeps Hockney’s work fresh and relevant, but also keeps him young. He still has a child-like quality and a fresh, eager curiosity in his eyes. “He’s living with technology as if he were a 20-year-old,” explains Goulds. “That curiosity has always been with him. He’s an image-maker. Yes, drawing and painting is the basis. [But] the big photo mural is the cornerstone of where we are now and where we are going.”

After the private seated lunch for the sitters, a meal served at one long table in the gallery (a first at LACMA), preceded by a group portrait in which artist Catherine Opie photographed 45 of the subjects in the adjacent space surrounded by their portraits, a VIP reception attracted everyone from Brad Pitt to director Christopher Nolan. Hockney is famously approachable and friendly, willingly posing for photo after photo with his friends and fans alike. He’s thoughtful with every person who approaches him and makes lots of eye contact—as if he is studying you to paint. “When I was finishing these portraits I did start looking back,” he admits, his ocean-blue eyes scanning his portraits. “I looked way, way back and that’s what made me see the reverse perspective. I’d used it before and then I realized I could do something with this today,” he explains, nodding toward the 25-foot photomural, his newest masterpiece. “I’ve really been looking back at my work in a way I hadn’t before for 20 or 30 years,” he reflects. “I’ve always said I live in the now.” “82 Portraits and 1 Still-life.” Through July 29, 2018. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, BCAM, Level 3, Nathanson Gallery, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A., 323-857-6000.

This story originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.