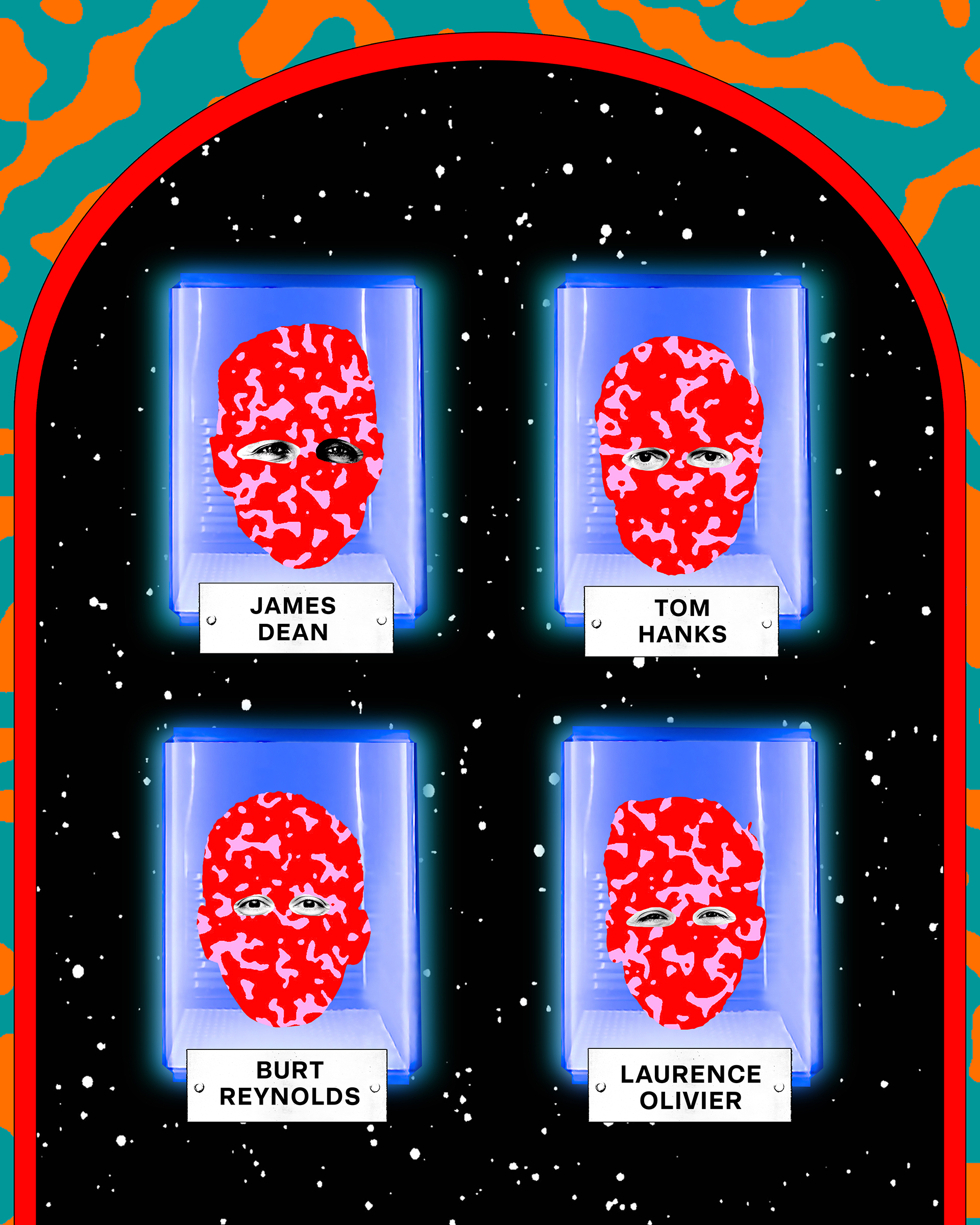

As it reincarnates the dead and reverses the aging process, who wins?

Words by STEVE SANDERS

Illustration by TYLER SPANGLER

In his latest film, Here, Tom Hanks, reunited with Forrest Gump director Robert Zemeckis, graces the screen with a head of bushy black hair and the youthful lilt to his voice not seen or heard since Bosom Buddies, the 1980s sitcom that launched his double-Oscar-winning career. A Lazarus-like James Dean, dead nearly 70 years, can now read your kids a bedtime story. And any YouTube influencer with a few minutes to spare can create a digital clone to record ads in their absence or to chat with their followers when they are indisposed.

Less than a year after Hollywood writers and actors ended their strikes with landmark agreements that, they declared, secured “unprecedented provisions to protect members from the threat of artificial intelligence,” the technology is blazing through the industry with alarming speed. It is “de-aging” stars like Hanks; resurrecting long-dead icons including Dean, Burt Reynolds, and Laurence Olivier; and, critics argue, stealing jobs from Hollywood, where unemployment is on the rise.

Last year’s historic strikes — it was the first time both actors and writers walked out since 1960 — marked the beginning rather than the end of the issues they will have to contend with as AI radiates across Hollywood. In July, SAG-AFTRA, the actors’ union that led last year’s strike over TV and streaming contracts, went on strike again, this time over how AI is being used to potentially replace video game actors.

AI voice models ingest millions of hours of human-generated audio to create lifelike voices that can recite any script they are given, fanning fears that thousands of humans could be replaced by machines that are cheap and that don’t grow fatigued or complain. The work stoppage affects more than 160,000 video game and voice actors, bringing to a halt a variety of new titles and those already in development.

“We’re just warming up right now,” said Tom Friedlander, the founder of the National Association of Voice Actors, a group that lobbies for the voice actors who, as a group, are mostly nonunion and thus not protected by any rights SAG might win. “We don’t even know what game we’re playing yet because it keeps changing. But we are trying to make sure that we are a part of this new technology that’s being built literally on the backs of our voices and on our biometric data. Right now, it’s just about protecting the ability to have this career even exist in a couple of years.” The most high-profile flashpoint came in May, when San Francisco–based OpenAI unveiled a voice assistant that sounded eerily similar to Scarlett Johanssen. The actor, who days before had turned down a personal offer from OpenAI’s billionaire chief Sam Altman to be the voice for the tool, sent a legal letter demanding answers. OpenAI denied it had used her voice but abruptly killed that version of its assistant.

There is still some way to go, however, before AI tools become true stand-ins for humans.

Countless additional conflicts could be in the offing. The deals reached last year with the writers and actors unions covered just two contracts of nearly 700 that govern how studios use AI and compensate workers.

In November 2022, OpenAI launched the AI era as we know it when it unveiled ChatGPT, its powerful chatbot capable of passing the bar exam, writing sequel scripts to blockbuster movies, and telling jokes. A sense of doom swiftly descended, as people feared this powerful new technology would wipe out entire industries. Hollywood is perhaps the most visceral embodiment of that angst, but it also represents opportunity.

Eleven Labs, a San Francisco audio cloning company, last month signed deals with the estates of Dean, Reynolds, and Olivier to allow the use of their voices for a “reader app” that recites audio books. Such deals offer novel revenue streams for any number of Hollywood stars — dead or alive — and their families. Liza Minnelli, the daughter of Judy Garland, who is also included in the Eleven Labs deal, said, “Our family believes that this will bring new fans to Mama and be exciting to those who already cherish the unparalleled legacy that Mama gave and continues to give to the world.”

Such tools are not useful just for stars. Eleven Labs requires as little as one minute of audio to create an instant clone, or 30 minutes for a professional-grade replica capable of imitating the style and intonations of an actual human. Startups like HeyGen in San Francisco and Hour One in Tel Aviv, Israel, can create video clones with as little as one minute of recorded video. They are part of a wave of cloning start-ups offering some version of the same pitch: AI allows anyone to “scale” themselves with digital clones capable of standing in for them and getting paid for work they do not want or have time to do.

There is still some way to go, however, before AI tools become true stand-ins for humans. In July, Meta shelved a line of celebrity chatbots, including the likes of Tom Brady and Snoop Dogg, after users ignored them entirely. Snoop’s bot, for example, garnered just 15,000 followers before Meta pulled the plug, compared with the 89 million the actual Snoop has accumulated. Meta sheepishly said it had taken “a lot of learnings” from the failed and very expensive experiment: The company paid millions to the stars to license their likenesses.

Creating digital copies of stars is unlikely to be the “killer app” of AI. A more likely outcome is that it opens new possibilities that are impossible today. “We talk about impossible jobs: things humans just couldn’t do,” Friedlander said. “Take the Olympic recap. You could get a personalized recap from Al Michaels, but there are 7 million different combinations of recaps that you could get, depending on your interests. Al Michaels couldn’t do that as a human.”

Amid the strikes and unrest, the central question is simple: Will AI take more opportunity than it creates? Consider Hanks. In Here, director Robert Zemeckis charts the life of a single family over decades. Without AI to de-age Hanks, a younger actor might have won a job to play him in his teenage years, or an older one might have been able to play him near the end of life. Instead, multiple jobs went to one of the wealthiest actors in Hollywood.

Rather like Forrest Gump and his box of chocolates, the majority of Hollywood still doesn’t know what it’s gonna get from AI.

This story originally appeared in the Fall Men’s Edition 2024 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.

See the story in our digital edition