Carl Hopgood’s transatlantic relocation led him to a new vocabulary for his mixed-media sculptures

Words by DAVID NASH

Photography by FRANK OCKENFELS 3

Three decades seems like a long career, but in the art world it’s a actually a drop in the paint bucket. L.A. multidisciplinary artist Carl Hopgood, whose sculptures often take the form of a seemingly precarious stack of chairs colorfully lit by affixed neon phrases, is just hitting his stride at age 53. Like his work, the recognition keeps stacking up, even when the odds are against him.

Last summer, a fire destroyed Hopgood’s Glendale studio. The building next door caught fire on a dangerously windy day, and firefighters couldn’t save the 3,000-square-foot studio where he had been working for five years. “It went up like a tinderbox,” Hopgood says from his Richard Neutra–designed Hollywood Hills home, which now doubles as his studio. He lost six completed works, sketchbooks, photographs, and a computer, as well as all his equipment and supplies.

I remember hiding under the stacked-up chairs in the school canteen — that was my place of sanctuary.

Carl Hopgood

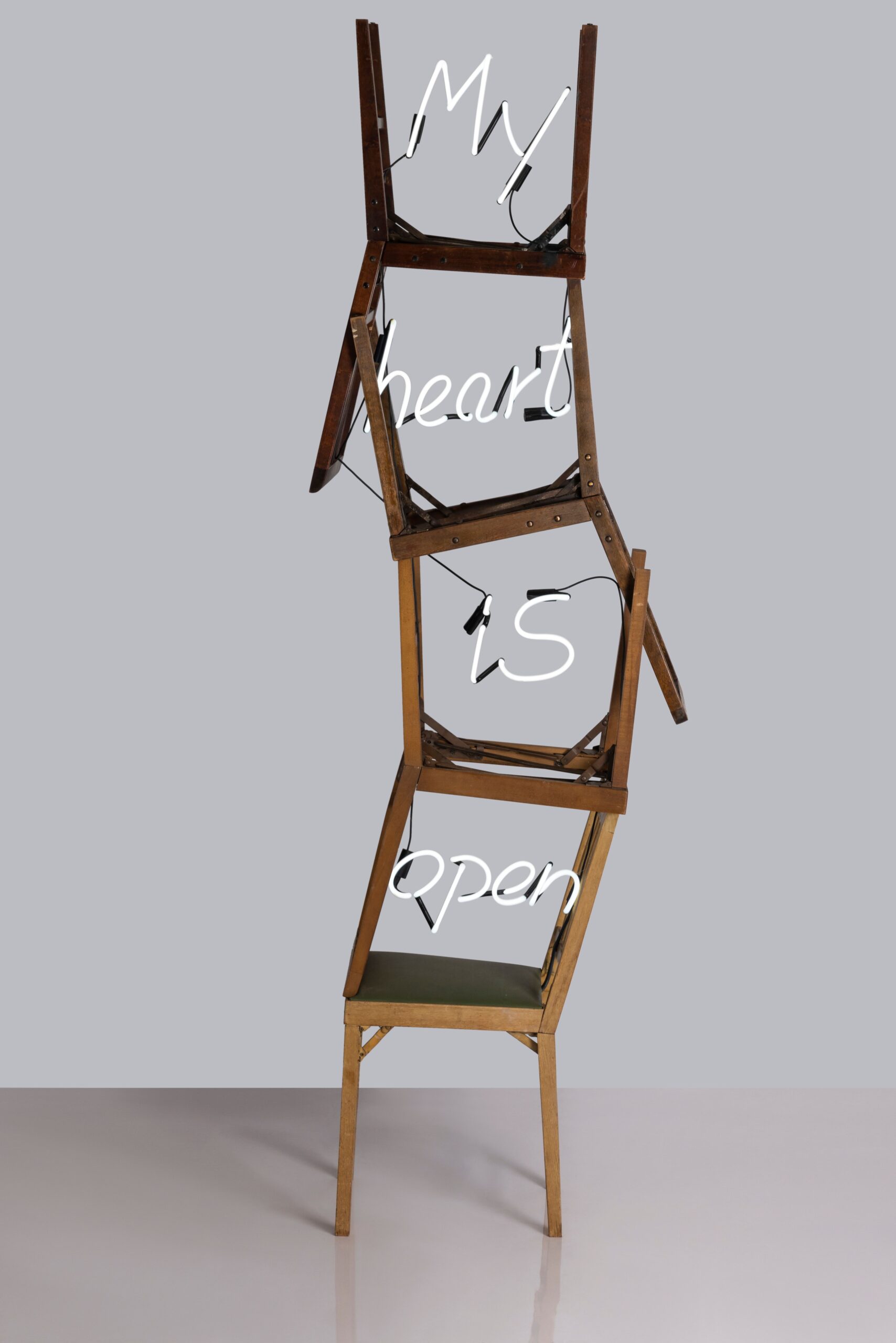

The past five years have been illuminating for the U.K. expat in more ways than one. His works reside in the collections of ARTnews “Top 200 Collectors” like Beth Rudin DeWoody and Eugenio López Alonso (the founder of Museo Jumex in Mexico City), as well as in those of aesthete patrons like Jim John and Craig Hartzman, Diane Allen, and actor Morgan Freeman. Earlier this year, one of his sculptures, Golden Sleeping Stag — a life-size, gold-leafed marble plaster cast of his own body (with gilded stag horns protruding from his head) lying on a bed — was included in MirrorMirror, Michael Petry’s survey of reflective works by 150 renowned artists for Thames & Hudson. In addition, the Palm Springs Art Museum announced the acquisition of his 2021 work My Heart Is Open, a four-chair sculpture with the phrase lit in white neon.

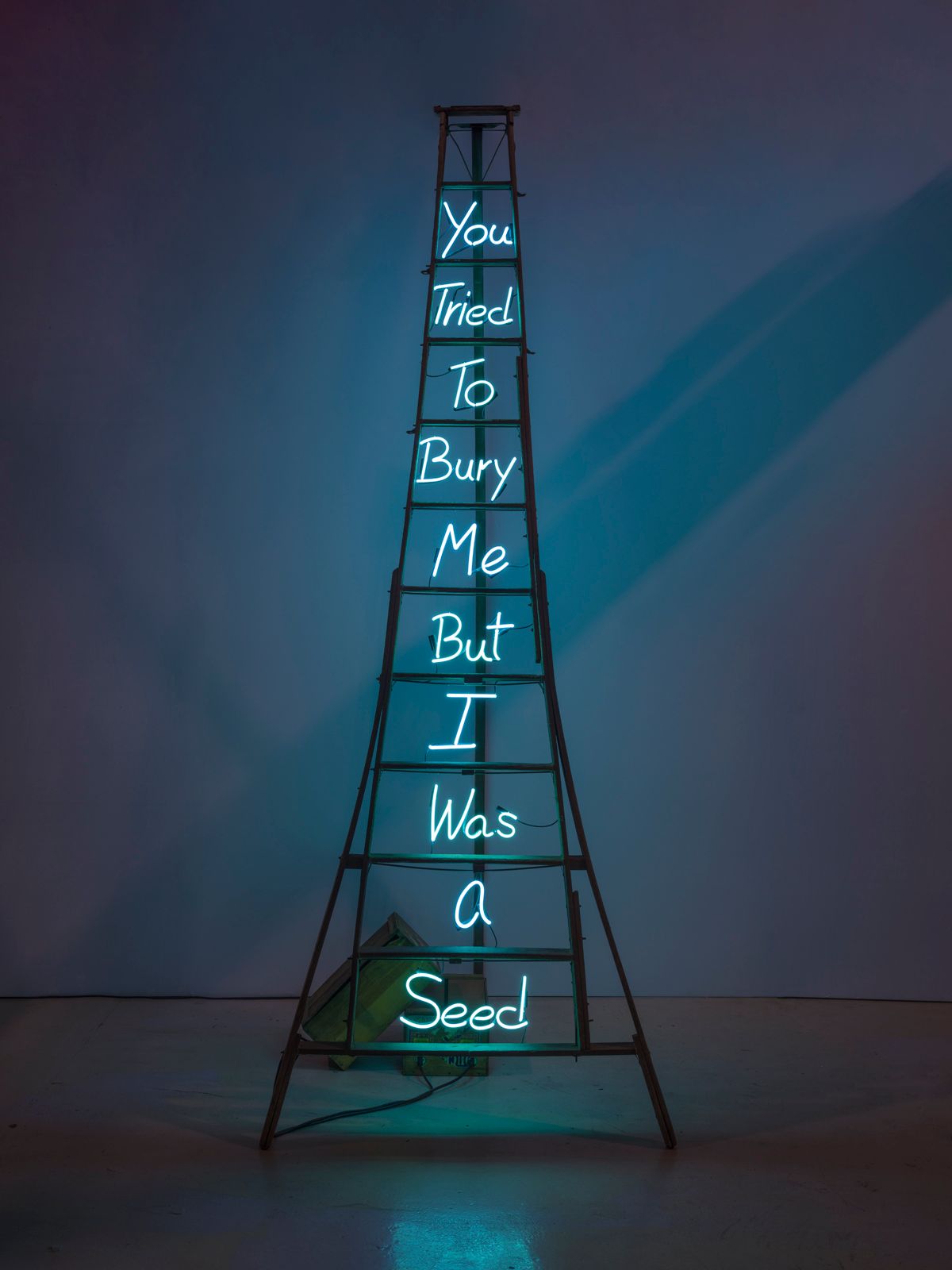

One sculpture survived the fire unscathed. “It ended up underneath some corrugated metal that acted like a wave of safety, deflecting the heat and flames,” Hopgood says. The work, aptly titled You Tried to Bury Me But I Was a Seed — a 12-foot vintage fruit-picking ladder with a bright blue neon word atop each rung — has always served as a symbol hope for the artist. Conceived as commentary on the Mexican labor force exploited by California’s citrus industry in the 1950s, it also holds a deeply personal resonance. “It was actually inspired by a couplet from contemporary Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was sidelined by the literati in the 1970s for being gay, and I connected with that text,” says Hopgood, whose childhood, although outwardly idyllic, was marked by the stigma.

A somewhat solitary childhood in St. Lythans — a hamlet outside Cardiff, Wales, where he was born — offered Hopgood plenty of opportunity to develop his artistic talents. “Even as a kid, I was always making art,” he says. “Like little installations inside cardboard mushroom baskets my gran would give me. They were these surreal landscapes made from shells and magazine cutouts that I’d carry around and show everybody.” Eventually Hopgood headed for Goldsmiths, University of London. There, he learned about the industry from Dublin-born artist Michael Craig-Martin, who in the 1980s influenced emerging British artists, most notably Damien Hirst. “It was an incredible time. And while he was my main tutor, we had others, like Lisa Milroy and Julian Opie, who’d invite us to their private gallery viewings,” Hopgood says. “We’d get a taste of what it might be like to be an actual practicing artist.”

I’m making work with a story behind it that a lot of people can relate to.

Carl Hopgood

After graduating in June 1994, he was picked up by two well-established London galleries. That September, Waddington Custot and Karsten Schubert gave him solo shows that included installations combining Super 8 mm and 16 mm film and sculptures like Sleeping Figure (a marble cast of a man on a metal bedframe with a film projection of the same man projected onto itself). “The flickering of the light through the celluloid film made the sculpture seem as if it was breathing,” he says. “At my [graduation] show, Charles Saatchi almost knocked over one of these sculptures as he squeezed into the cubicle to see the front of Shower Piece — a sculpture of a naked man standing in a shower — that was designed only to be seen from behind.”

Soon, his work was displayed in exhibitions outside the U.K. “I showed in Australia and Italy — in Rome I exhibited at the Studio d’Arte Contemporanea Pino Casagrande,” he says, noting that Shower Piece resides in the private gallery’s permanent collection. During this period, Hopgood also worked as an editorial set stylist under Simon Costin, the set designer known for his collaborations with Alexander McQueen. “We were always using chairs as props, and I had a really good collection,” he says. “We were shooting people like Kate Moss, Linda Evangelista, and Sharon Stone on them for British or Japanese Vogue or V Magazine, but I never realized how that would inform my practice years later.”

In 2015, Hopgood moved to the U.S. just as one of his London galleries, the Maddox Gallery, was opening an L.A. outpost. “I always loved David Hockney and watched films about his journey from London to L.A. that really inspired me,” he says. “It meant a whole new market and the freedom to work with different mediums.” After landing in West Hollywood, he began to combine neon with his found objects, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that a proverbial light bulb went on. “I’d walk past all these shuttered restaurants and bars and see chairs stacked on top of each other,” Hopgood says. “I wanted to make something in that difficult moment and, I suppose, use it as my therapy.” Seeing towers of chairs also dredged up memories of being bullied as a young schoolboy that brought deeper context to his work. “I remember hiding underneath the stacked-up chairs in the school canteen — that was my place of sanctuary.” It was a full-circle moment for Hopgood that brought purpose to his art. “I’m making work with a story behind it that a lot of people can relate to.”

He began constructing the mixed-media sculptures for a 2021 show at Maddox. One of the works, My Heart Is Open, was quickly acquired by the Vinik Family Foundation in Tampa, Florida. After the show, Arthur Lewis (then the creative director at United Talent Agency’s fine arts division) visited Hopgood’s studio, leading to his inclusion in a 2022 group show called Fragile World. “I made one of the last pieces for the show, Just Say Gay, really quickly in response to [the Florida Legislature’s] ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill that pushed back against the LGBTQ+ community,” Hopgood says. The timing couldn’t have been better: [Beth Rudin] DeWoody was in attendance, purchased the piece, and displayed it the following year at her West Palm Beach venue, The Bunker Artspace. Another piece from the earlier show, You Changed My Life, was acquired by Bronwyn Newport, who — as a collector and cast member on the fifth season of The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City — gave the work a star turn by unveiling it on camera.

Currently, Hopgood has a pop-up show at RVD Associates’s design studio on Melrose and a June show at Madsen in Los Altos. He’s also working on two big projects: cocurating a 2026 exhibition based on MirrorMirror at King’s Cross Town Hall in association with MOCA London, and producing Fragile World, a documentary chronicling his activist art that will premiere at the Iris Prize LGBTQ+ Film Festival in Cardiff in 2026. “I’ve also started a new body of work based on some metal chairs that survived my studio fire,” he says. “Things like that have to push you forward, like a phoenix from the flames.”

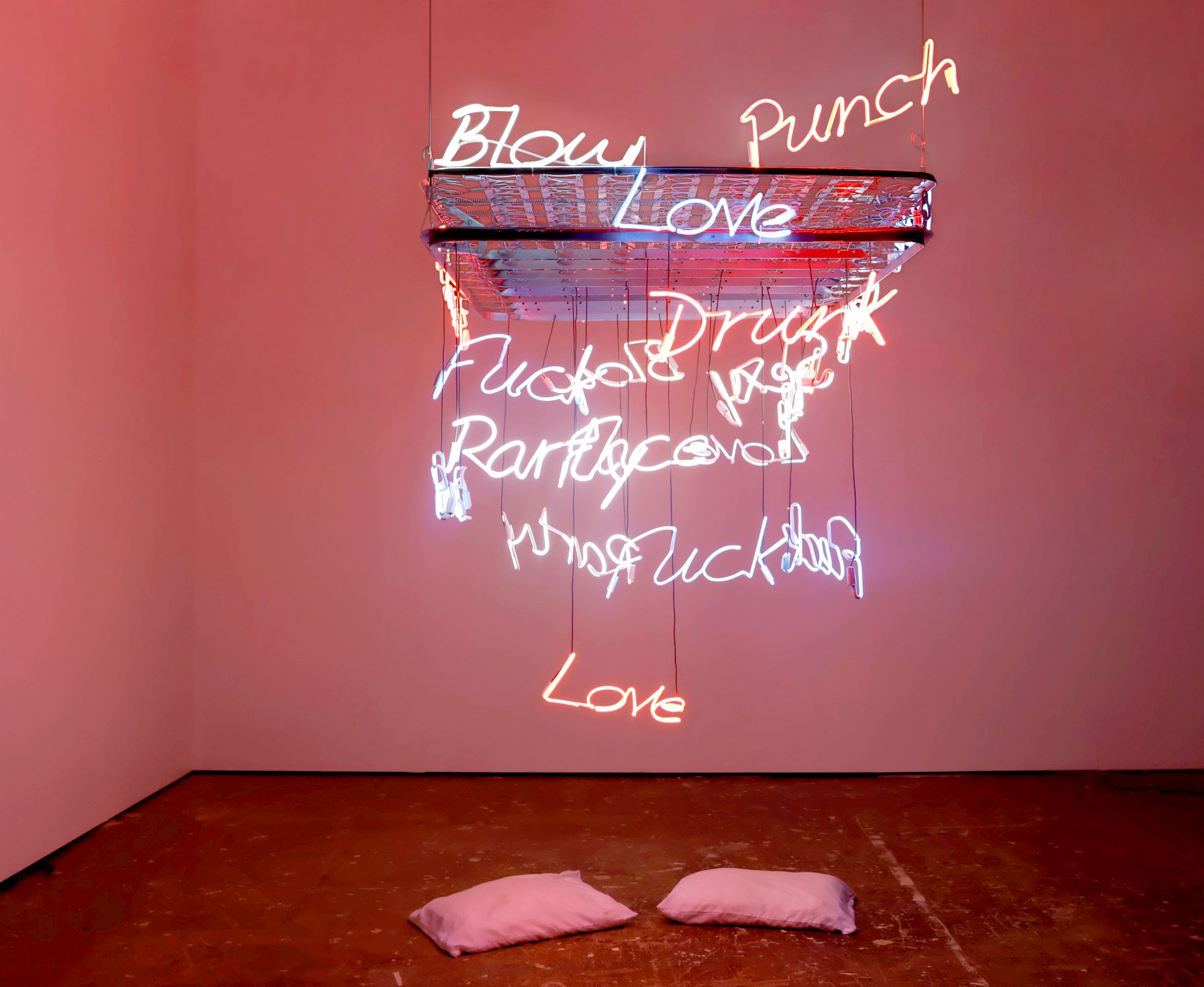

Feature image: Far From Fear (2022).

This story originally appeared in the Men’s Spring 2025 edition of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.

See the story in our digital edition