California’s cultural boom has redrawn the global arts map via billion-dollar museums, blockbuster galas, and a creative spirit all its own

Words by DEGEN PENER

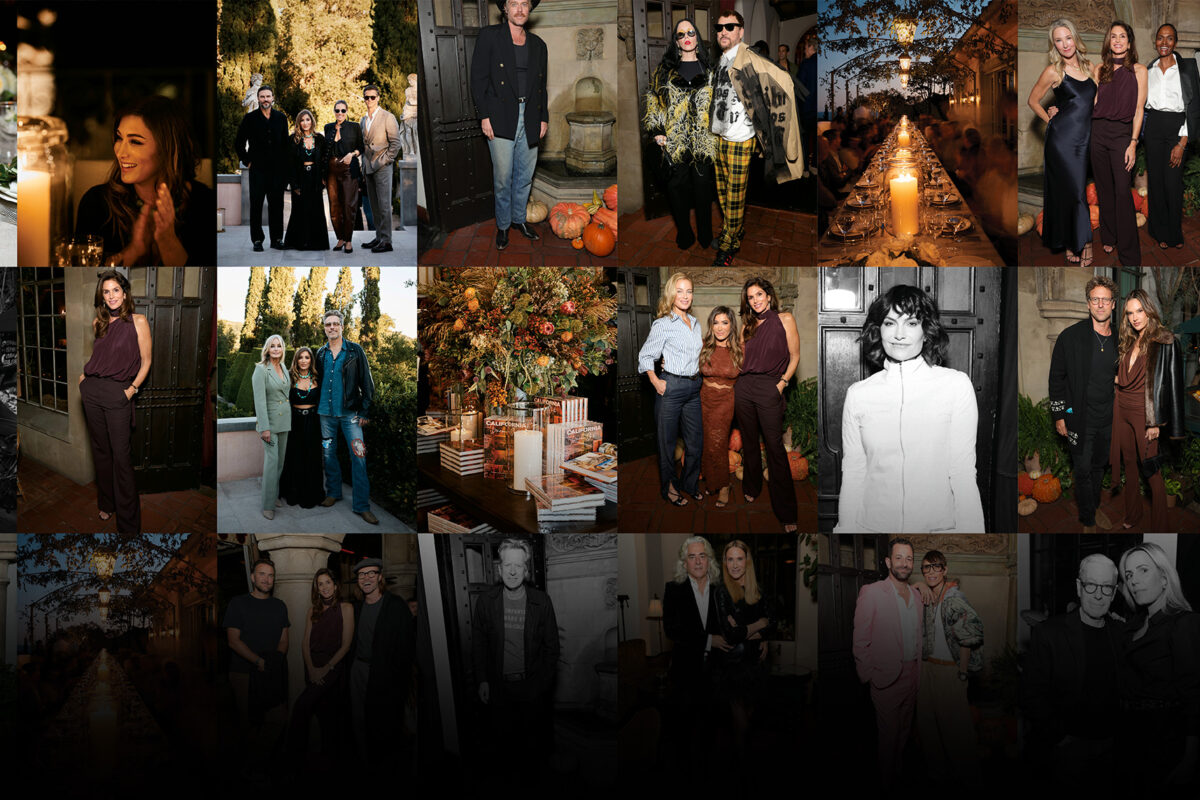

Museum galas don’t typically rival the Oscars when it comes to celebrity turnout. That’s why the 2011 debut of LACMA’s Art+Film Gala felt like such a game changer for the art world.

Everywhere you looked was another one of your favorite stars — Emily Blunt, Olivia Wilde, Jane Fonda, Zoe Saldaña, Jon Hamm, Reese Witherspoon — decked out in the latest creations from the event’s founding sponsor, Gucci. Benefit cochairs Leonardo DiCaprio and Eva Chow, who envisioned the evening as a glittering convergence of L.A.’s creative worlds, also welcomed to the red carpet California art stars like Mark Bradford, Catherine Opie, Edward Ruscha, Doug Aitken, and Barbara Kruger. The evening honored two California visionaries: director (and longtime Carmel resident) Clint Eastwood and conceptual artist John Baldessari. DiCaprio enjoyed himself so much that he stayed out until nearly midnight. Within five years, GQ had dubbed the annual benefit the “Met Gala of the West,” and it has since raised more than $51 million for the museum.

“This was always a city about film; now it’s a city that’s also about art,” Dawn Hudson, who was then the CEO of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, told me that night. “So the fact that we are celebrating both in the same place is pretty special.”

“This was always a city about film; now it’s a city that’s also about art.”

The message was impossible to miss: California — once an artistic frontier and long a fertile proving ground for exploration and creativity — was declaring itself a powerhouse on the international art scene. After decades of operating in the shadow of New York, the Golden State was in full creative bloom.

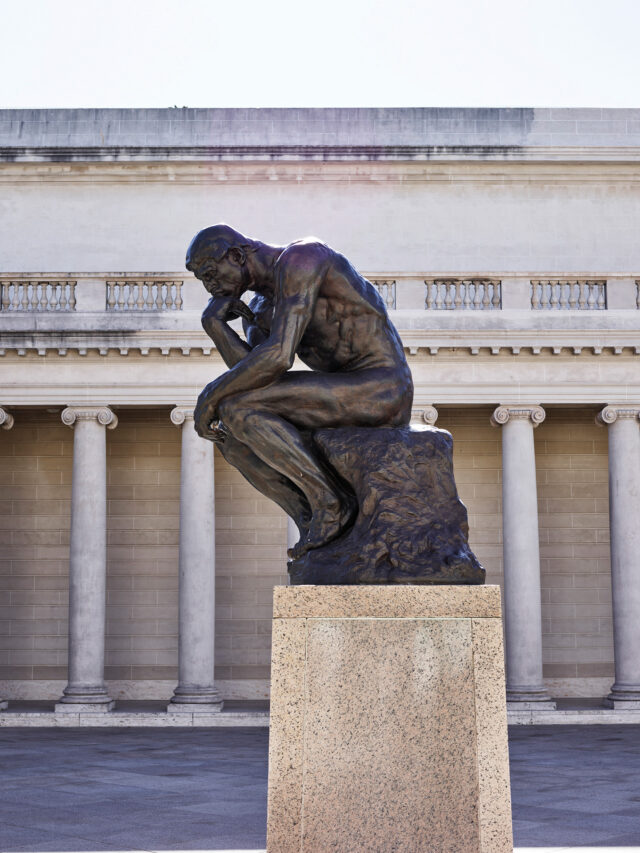

You had already sensed it at the 2005 opening gala for the Herzog & de Meuron–designed de Young Museum, a striking, perforated-copper home for the institution’s encyclopedic collection of artworks spanning 5,000 years. That night, Gavin Newsom, then the mayor of San Francisco, looked around the 3,200 guests and — never one to undersell — exclaimed, “I’m blown away. This is an incredible gift to the city.”

You felt it at MOCA’s spectacular 30th anniversary benefit in 2009, where Lady Gaga debuted her song “Speechless,” playing a Damien Hirst–designed pink piano and wearing a hat created by Frank Gehry.

And you experienced it when a 31-year-old Gustavo Dudamel, the music and artistic director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, marshaled two orchestras to play Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 on February 4, 2012, at the Shrine Auditorium, along with 813 singers from 16 local choruses and eight soloists.

If California’s art scene was finding its swagger, nothing embodied that confidence more than the buildings themselves, as a string of gleaming new and reimagined cultural palaces sprang up across the state with a combined price tag of more than $4 billion.

After the de Young opened, multimillion-dollar expansions and renovations of such institutions as The Getty Villa (2006), the Huntington (2008), the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (2021), the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (2022), the Asian Art Museum (2023) in San Francisco, and the Hammer Museum (2023) followed. Each debut felt like part of a larger civic competition, as though every part of California wanted to prove that it, too, could play on the world stage.

Entirely new institutions have also arrived, further shifting the cultural map.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s 2016 expansion was yet another game-changing moment. Its elegant 10-story new Snøhetta-designed addition, with an undulating white facade inspired by the waters of San Francisco Bay, tripled the museum’s exhibition space and gave it more square footage to display art than the Museum of Modern Art in New York has. It also became the dazzling new home for the blue-chip Fisher Collection, a 100-year loan from the founders of Gap. Six years later, Orange County Museum of Art moved into its new Morphosis-designed building in Costa Mesa, a sculptural concatenation of bold geometric shapes clad in white-glazed terra-cotta.

Under Michael Govan’s leadership, LACMA has been completely transformed. After the addition of the Renzo Piano–designed BCAM and Resnick buildings more than 15 years ago, the museum is now preparing its most audacious architectural statement: the $720 million Peter Zumthor–designed David Geffen Galleries, a thrusting expanse of concrete and glass that hovers over Wilshire Boulevard. It’s expected to open next spring.

Entirely new institutions have also arrived, further shifting the cultural map, including the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco, Museum of the African Diaspora in S.F., Hilbert Museum of California Art in Orange County, and The Broad. With its honeycomb-like facade, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, The Broad sits as a delicate architectural counterpoint to its neighbor, Frank Gehry’s brashly swooping Walt Disney Concert Hall.

“We thought we would have about 250,000 visitors a year,” its founder, Eli Broad, once wrote. That estimate turned out to be way off. Last year, the museum, which opened in 2015, welcomed more than 820,000 visitors to see its permanent collection and a retrospective of work by Mickalene Thomas. And it’s already planning a major expansion to be completed ahead of the 2028 Olympics in L.A.

Finally, in 2021, Hollywood got its own museum, with the opening of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, featuring the distinctive Renzo Piano–designed Sphere, which hosts the museum’s own gala, a competitor with LACMA’s Art+Film Gala for the title of Met Gala of the West. At last year’s event, says Amy Homma, the museum’s director and president, “Quentin Tarantino surprised us by bringing out the original handwritten script to Pulp Fiction and donating it to us.”

These buildings announced to the world California’s ambition to be a global center of art and culture. And they rose in lockstep with California’s booming economy, which this year overtook Japan to be the fourth-largest economy in the world.

The performing arts answered with its own new temples of culture in the last two decades, including the Cesar Pelli–designed Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall (2006) in Orange County and the jewel-box Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts (2013) in Beverly Hills.

But undoubtedly the biggest story on the performing arts front was the arrival of the dynamic Dudamel at the LA Phil. While its previous music director, the elegant Esa-Pekka Salonen, elevated the orchestra into first-tier status in the U.S. and gave it a reputation for experimentation, Dudamel shifted everything into creative overdrive.

Part of California’s newfound cultural dominance resulted from a look at its past.

During his remarkable 16-year run at the orchestra (he leaves next year to lead the New York Philharmonic), the LA Phil played Coachella, staged ambitious operas at Walt Disney Concert Hall, and celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Hollywood Bowl, to name just a few highlights. And YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles), which Dudamel founded, performed at the Super Bowl twice.

“He was 26 when he started, and he just transformed what we envision an orchestra can be,” says Meghan Umber, the chief programming officer at LA Phil. She points to a trilogy of operas Dudamel staged between 2012 and 2014 as particularly magical, pairing fashion designers (Rodarte, Azzedine Alaïa, Hussein Chalayan) with architects (Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid). The transformation wasn’t just artistic; it was financial. By 2023, the LA Phil’s annual revenue had soared to $208 million, nearly double that of the New York Philharmonic. In a twist, Salonen will return to the LA Phil as its creative director, as the orchestra searches for a new music director.

Dance in California also attr-acted the world’s biggest players, from Benjamin Millepied, who founded the innovative L.A. Dance Project in 2012, to Tamara Rojo, who took the reins of San Francisco Ballet in 2022. As if her hit 2024 production of the artificial intelligence–themed ballet Mere Mortals weren’t enough, the company announced last year that it had received a jaw-dropping $60 million gift from an anonymous donor — a huge vote of confidence in the company’s next era.

Interestingly, part of California’s newfound cultural dominance resulted from a look at its past. In 2011, the Getty launched its game-changing initiative, Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A., 1945 to 1980, which helped fund exhibitions on California’s artistic history at more than 60 cultural institutions across Southern California. Its message, as Vogue put it at the time, was that “modern art developed differently on the West Coast, and the New York–centric art world has ignored its contributions for far too long.” There were dazzling surveys of California artists at both Getty and MOCA, a phenomenal LACMA exhibit on California design, and the sublime Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface show in San Diego, where works by 1960s Light and Space artists like Robert Irwin, James Turrell, Mary Corse, Bruce Nauman, Larry Bell, and Helen Pashgian shimmered.

The impact was seismic. “It was a coming of age for a city that sometimes doesn’t think of itself as having an art history,” said LACMA’s director, Michael Govan. Adds Maria Bell, the chair of the LA28 Cultural Olympiad and a former board chair of MOCA, “What the Getty did in bringing together all of these cultural institutions was transformative.” Since then, the Getty has doubled down twice more with Pacific Standard Time LA/LA (spotlighting Latin American and Latino art) and PST Art: Art and Science Collide. Each chapter reinforced the story that California has always had a rich narrative of its own.

The love for California artists continued at major museums, where acclaimed retrospectives of established names included shows of Barbara T. Smith at the Getty; Andrea Bowers, Charles Gaines, and Lari Pittman at the Hammer; Mike Kelley and Henry Taylor at MOCA; Betye Saar, James Turrell, and Frank Gehry at LACMA; and Joan Brown, Ruth Asawa, and Jay DeFeo at SFMOMA.

The state also became a magnet for a new generation. It increasingly attracted young artists, many of whom were drawn to the state’s acclaimed art schools. (UCLA in particular has a remarkable history of major artists, such as Baldessari, Kruger, and Opie, serving as faculty.) In 2023, 22 percent of all fine arts degrees in the country were conferred in California, according to Otis College of Art and Design’s most recent Creativity Economy report. “Until very recently, L.A. was reasonably affordable for a big city — less expensive than New York and London. So the scene has swelled,” says artist Meg Cranston, the chair of the fine arts program at Otis.

With all that influx of young talent, museums took note. The Hammer’s “Made in L.A.” biennial became a launchpad for emerging painters and sculptors. The de Young created the de Young Open, inviting Bay Area artists into a salon-style triennial. And in 2022, OCMA brought back the museum’s California Biennial.

Of course, California’s cultural boom didn’t happen in a vacuum. Collectors, too, shifted their gaze. Where once they might have looked east for validation, many began rooting their collections locally. “There are so many collectors who have really focused on L.A. artists,” Bell says. “The artists were here, and you could see their work in their studios. For collectors, that creates a real connection.” Money was flowing into the art world at unprecedented levels, and as California’s economy surged the global art market noticed — and wanted in.

Over the past dozen years, some of the most powerful galleries in contemporary art have planted flags in L.A., including Pace, Sprüth Magers, David Zwirner, Jeffrey Deitch, Matthew Marks, Lisson, Perrotin, and Marian Goodman. Hauser & Wirth opened two locations, including its museum-like compound, replete with restaurant, in a former flour mill downtown. Part of the expansion was pragmatic; many of these galleries represented L.A. artists.

Then came the rocket booster. In 2019, international art fair Frieze landed in L.A. Celebs like DiCaprio and Gwyneth Paltrow became regular attendees, and dealers, collectors, and curators from around the globe built L.A. into their calendars. “The whole sector of the art world that travels from Asia, Europe, and over America, they come to Los Angeles in February for Frieze Week,” gallerist and former MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch said in 2024. “It’s a remarkable community celebration.”

Homegrown fairs joined the mix too. Palm Springs’s Modernism Week — next year will be its 20th anniversary — turned midcentury architecture into a cultural pilgrimage. The Bay Area welcomed the annual FOG Design+Art fair, which brings together top galleries and high design. And since 2017, Desert X has turned the Coachella Valley into an open-air gallery every other year, featuring often monumental site-specific works like Doug Aiken’s Mirage — a house of mirrors that shimmered on the horizon.

Dance also attracted the world’s biggest players.

What’s made California’s rise so exhilarating is that it rarely follows the traditional scripts of the art world. That’s made for exciting cross-pollination among disciplines, as well as an embrace of creative endeavors that haven’t always been considered high art. Exhibit A was MOCA’s Art in the Streets show of street art in 2011, setting an attendance record at the time with more than 200,000 visitors. “We’ve seen museums, theaters, and even outdoor venues become more accessible by breaking down traditional barriers between art forms and audiences,” Homma says.

Underrepresented artists have also won greater representation over the past two decades. Two prominent examples are the 2022 opening of the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture in Riverside and the Hammer’s 2011 exhibition Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980. And in 2018, likely for the first time in L.A., female artists were the subjects of more solo shows than male artists at major museums in the city.

Expect many of these trends to continue. According to Otis College’s Creative Economy report, employment in California’s fine arts sector is the only one of nine tracked industries to add jobs statewide for two consecutive years. And next year, in addition to LACMA’s new building, L.A. will welcome the spaceship-like Lucas Museum of Narrative Art (a long-time dream of George Lucas and Mellody Hobson). Additionally, in late 2025, digital artist Refik Anadol’s AI-themed museum Dataland is expected to bow in DTLA across from The Broad.

One thing is clear: California is no longer an underdog. As Umber sees it, that presents a special kind of challenge — the pressure to “continue always succeeding. That’s one of the hardest things to do — to lead from success. I think that’s kind of where we are now.”

Feature image: The LACMA Art + Film Gala 2024. PHOTO: Zach Hilty/bfa.com.

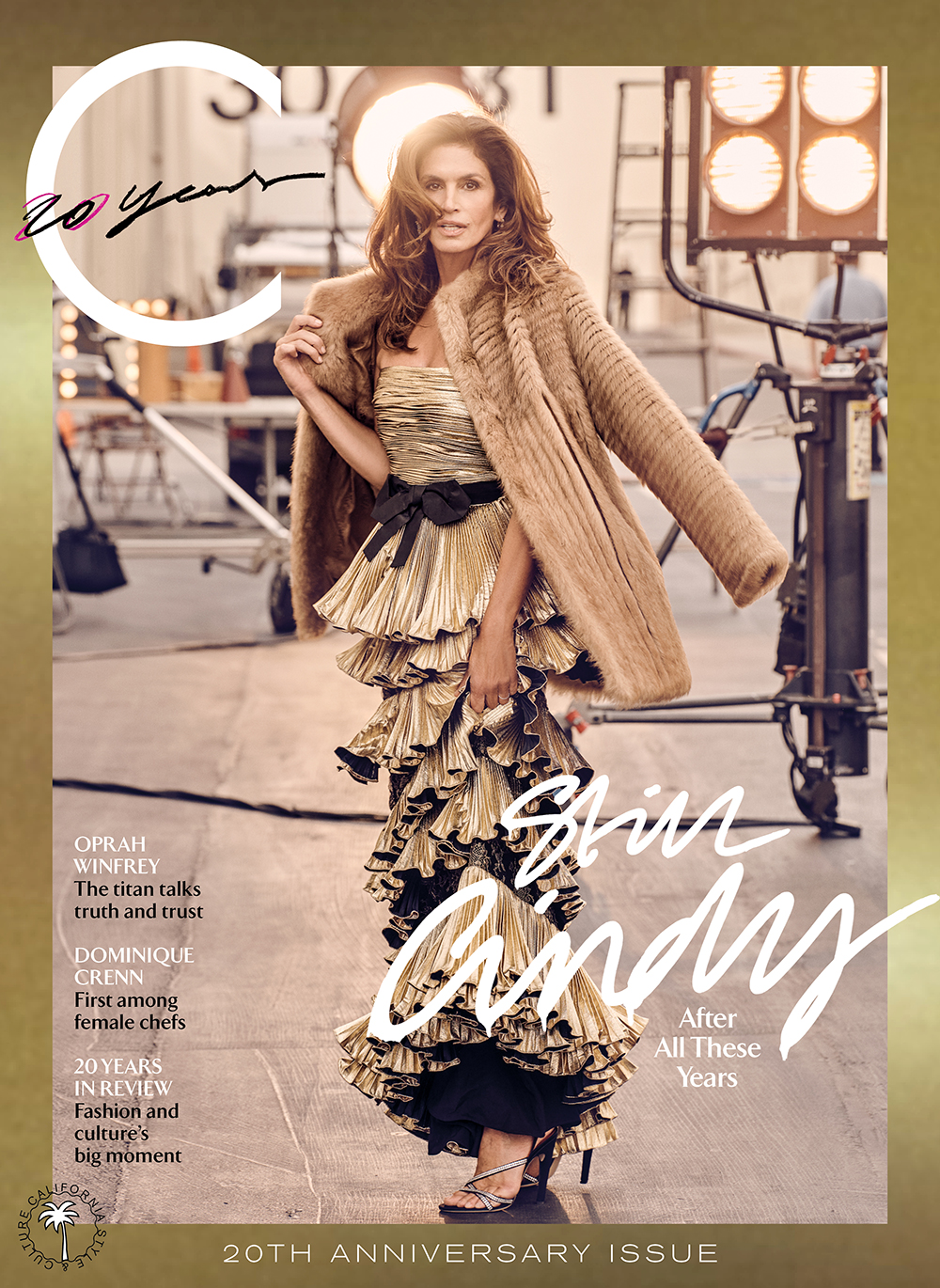

This story originally appeared in the 20th Anniversary 2025 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.

See the story in our digital edition