A new generation falls for the literary icon’s Golden State-inspired prose in a forthcoming essay collection

Words by STEFFIE NELSON

In The White Album, Joan Didion famously wrote that “a place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively … loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image” — criteria that made California hers for all time. Slouching Towards Los Angeles: Living and Writing by Joan Didion’s Light is a celebration and an investigation of Didion’s ongoing claim on California and its writers — because she, in turn, belongs to us.

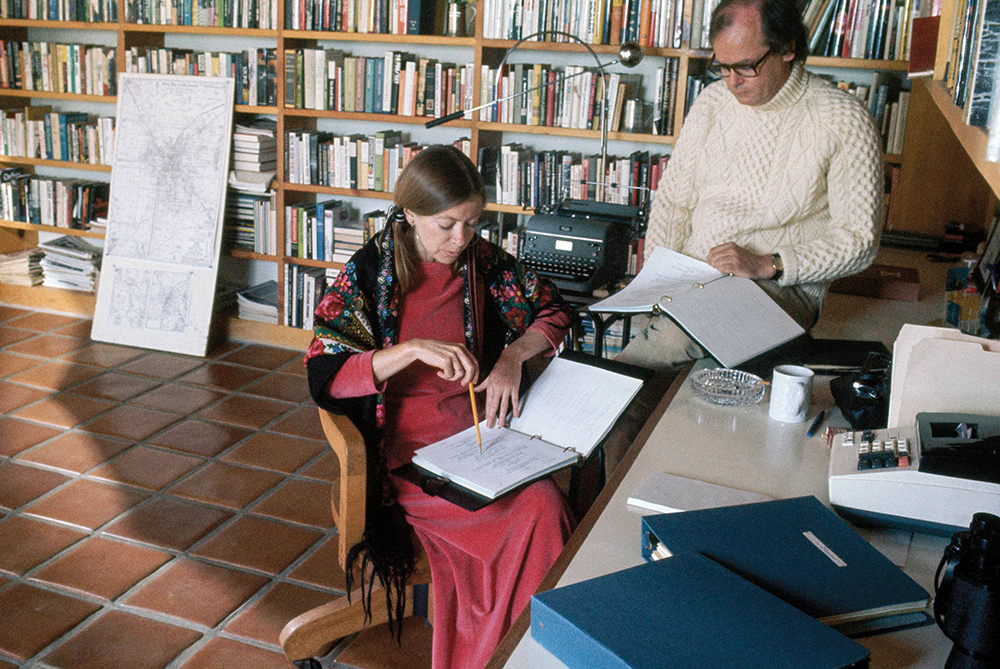

Joan Didion grew up in Sacramento, went to college in Berkeley, and then, after a stint in New York City during which she worked at Vogue and met her husband, John Gregory Dunne, she returned to California in 1964 to live for 24 years in Los Angeles. These years were ones of radical change — from the rise of the counterculture through the Reagan era — and in that time Didion became the city’s most important public intellectual, elevating L.A. beyond Hollywood and Hollywood beyond itself. She held California up like a diamond, revealing each facet (and flaw) through meticulous and surprising detail, startling psychological insights and prose so clean it’s incandescent.

Slouching Towards Los Angeles is a love letter and thank-you note, personal memoir and social commentary, cultural history and literary critique. It offers a portrait of a writer and her readers that is as multifaceted as the work that inspired it. Each author finds a unique entry point. Some meet Didion on the L.A. freeways or Franklin Avenue. Others are more connected through inner landscapes. Some gaze at a photograph — a fleeting instant captured in Hollywood or Malibu — until it speaks its truth. A few enter through side doors like Didion’s recipe collection and the Sacramento state archives. Still others share personal histories that take us to Brentwood’s Mandeville Canyon and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, after the hippies.

For my own essay “Dark Mirror: Reflections on the Golden Dream” (and the title of this tribute), I turned to the pages of Didion’s seminal 1968 book, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The collection grapples with the cultural values of California, and the connection between identity and place — subjects that remain every bit as compelling today.

• • • • •

“This is a story about love and death in the golden land, and begins with the country.” Those words, the first sentence of the first essay in Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, struck me as vividly as the sunshine-yellow and Day-Glo-orange cover I found tucked into my mother’s bookshelf one summer after college. I was an aspiring magazine journalist with a creative writing degree, but Didion had eluded me until that moment, like so many things that don’t appear until we’re ready for them. I’d studied Yeats, though, and I recognized the nod to his poem “The Second Coming,” in which a sphinxlike beast turns its “blank and pitiless” gaze, and slowly moves its thighs. …

It was as if I’d been handed a psychic map pointing west

Steffie Nelson

So it was actually the Irish poet — and the acid hues of that 1979 edition, which currently sits on my bookshelf — that led me to this woman whose writing lit up some nerve center in me, speaking to me in a language I’d never heard before, about a California where the sun’s gaze was as pitiless as a beast’s. Somehow I didn’t read futility in her words; I felt desire, and a willingness to risk everything for the prize. Teetering on the edge of adulthood, it was as if I’d been handed a psychic map pointing west.

Love. Death. The golden land. The country.

That opening line of “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream” is so simple yet so loaded with meaning, it’s almost a mantra. It reveals nothing but promises everything, and puts us in the driver’s seat — because in a flash, epic crimes and passions and landscapes unfurl like teaser reels across our minds. You might even call it lazy, leaning as it does on the reader’s imagination, but that’s the territory of the essay, anyway: the chasm between the glittering projection and what pans out. We’d like to believe that the dream will send us directly over the rainbow, reinvented and renewed, with pockets full of shiny nuggets and a suntan, too. But of course, the odds are against us. In this land, despair is bred at the same rate as hope, and Didion places her bets on the former. In fact, when this essay was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1966, it was titled “How Can I Tell Them There’s Nothing Left?”

On the surface the tale of a marriage gone sour, an illicit affair and a murder, Didion frames this exurban tragedy as the Golden Dream running its inevitable course and, in so doing, flips the narrative so that the dream is more defined by its end than its beginning. Without the flameout (in this case Lucille Miller’s literal incineration of her husband, Gordon, in the passenger’s seat of their Volkswagen in Bakersfield), we only know half the story.

“Of course she came from somewhere else,” we are told about the 35-year-old mother of a teenage daughter, “for this is a Southern California story.” From the start, it’s obvious that nothing good can happen in this place just an hour east of Los Angeles, where the winds blow hot and women cobble their aspirations from movies, newspapers and the radio. According to her father, Lucille Miller “wanted to see the world.” In this setup that was her fatal flaw.

What she did get to see was the 1-acre lot through her picture window, and it wasn’t enough. Didion visited the California Institution for Women at Frontera, where Miller was incarcerated after being convicted of murder in the first degree, and found it to be populated by “murderesses … girls who somehow misunderstood the promise.” This was already clear about Miller, she implies, from the high lacquered hairdo she’d worn in the courtroom: as ready for her close-up as Norma Desmond ever was.

“The dream was teaching the dreamers how to live”

Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Didion shows no compassion for Lucille Miller, but I find it hard not to pity this woman who was self-aware enough to realize that she’d settled for a life that would never fulfill her, and foolish and corrupt enough to think she could change her fate by burning her husband alive — an idea that came to her after watching Double Indemnity. The question is, when and where did the schism happen? Recounting the boilerplate B-movie dialogue exchanged by Miller and her lover, who’d promptly abandoned her once she was accused of murder, Didion asserts, “the dream was teaching the dreamers how to live.” But was it fiction dictating the script, or was this the glass Didion herself was looking through?

She’s such a master at manipulating the tension between utopia and dystopia that many L.A. writers — most of us from somewhere else, too — have internalized this queasy balance as our geographic destiny. But I’ve lived in Los Angeles for more than a decade, and I still don’t know if I’ve been to that pitiless place. I believe I’ve shielded my eyes against the same slanting sun and heard the Santa Anas rustling through the eucalyptus like snakes, but are those actual memories or just impressions left by language? They are like phantom experiences, in which sensations exist without physical cause.

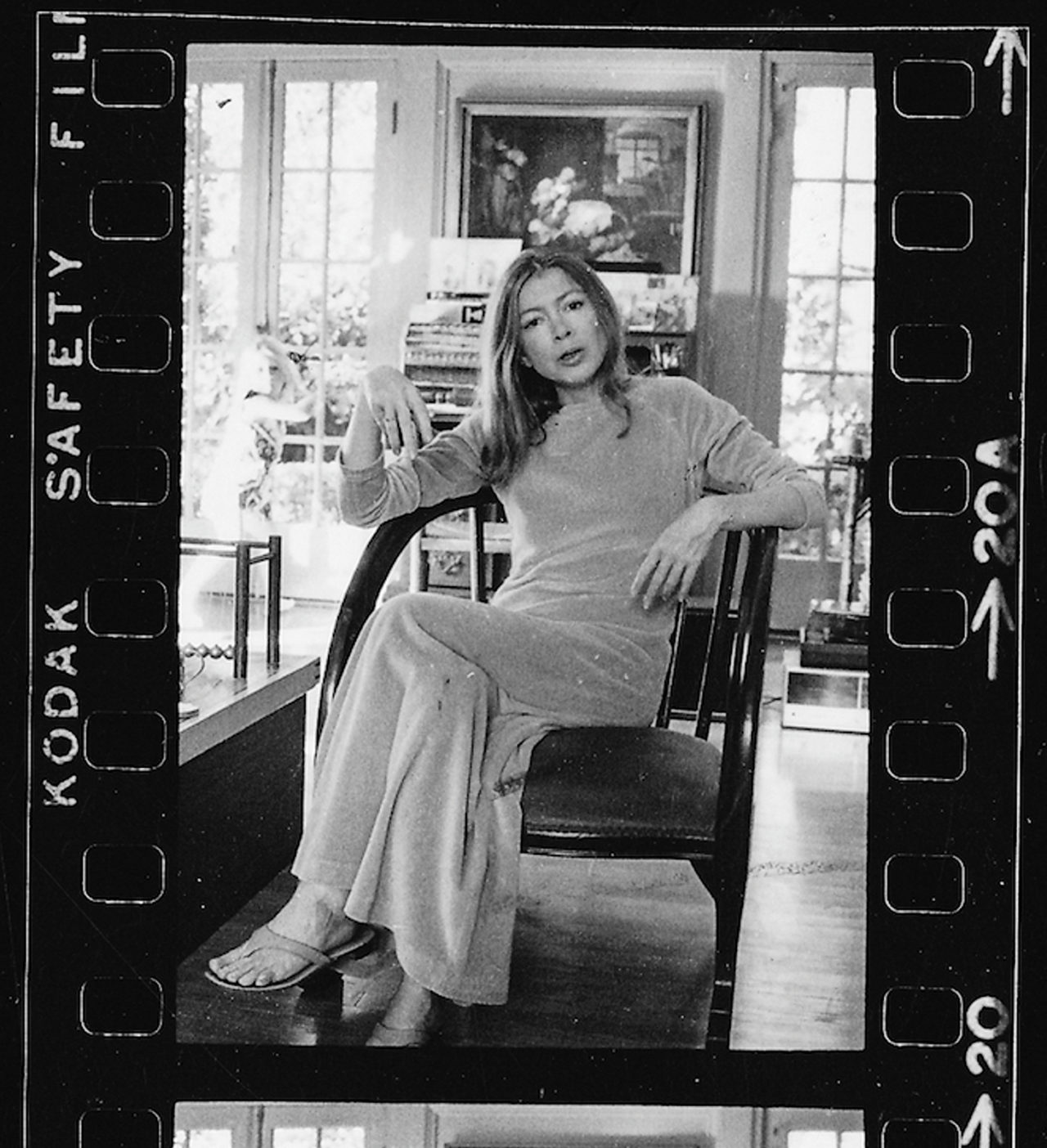

“The future always looks good in the golden land, because no one remembers the past,” Didion famously claimed in this essay. However, looking at the now iconic portraits of the young writer, I see a woman who is reluctant to smile for the camera, as if happiness or hope were somehow naive, given all that she knows. By any account she actually was living the dream during this time, but the passionate gratitude her fans have for Joan the person can be explained, I think, by our certainty that she never bought into the myth. She had seen the world and accurately gauged its promise. And then she made her place in the sun anyway — defying her own odds. There she will remain, plain and uncompromising, arms crossed — nobody’s fool, nobody’s victim. The fact that her darkest human dread was borne out, decades later, makes her youthful vigilance seem that much more exacting.

I’ve often wondered whether Didion, an avowed atheist who has stated her belief in “geology” over a personal God, knew about Yeats’ dedication to mysticism and the occult when she borrowed the title of her collection from him. His language brilliantly lends itself to the explosive creativity and chaos of the late 1960s — like the “sages standing in God’s holy fire” from his second most famous poem, “Sailing to Byzantium” — but “The Second Coming” also alludes to a pagan awakening that definitely suits the era but may not have suited Joan. Still, I’d like to think that somewhere within her solemn heart — maybe in the part of her that walked onto airplanes barefoot and gave her daughter the impossible, romantic name of Quintana Roo — she found space for a golden dream to drift in, and a center that would hold.

Excerpted from Slouching Towards Los Angeles: Living and Writing by Joan Didion’s Light, edited by Steffie Nelson (Rare Bird Books, $27), available February 2020.

REQUIRED READING

- In 1963, Didion published her first novel, Run River — a haunting portrait of a California family with underlying commentary on the history of The Golden State.

- Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion’s collection of essays largely about California in the 1960s, was published in 1968 to critical acclaim.

- Didion published her second novel, Play It as It Lays. The story of a Hollywood starlet who descends into madness, it exposes the dark side of the California dream.

- In 1979, Didion released a second book of essays, The White Album, featuring works that previously appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, Life and The New York Times, among other publications.

- The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion’s memoir about her marriage and the year of grief that followed the death of her husband, was published in 2005 and named a Pulitzer Prize finalist. The same year, her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, tragically died from acute pancreatitis at the age of 39.

- In 2011, Didion published Blue Nights, a memoir about her daughter’s adoption, parenthood, aging and her daughter’s untimely death.

Feature image: The couple and their daughter, QUINTANA ROO DUNNE, in Malibu in 1976. Photo by John Bryson/Netflix.

This story originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.