From her Topanga Canyon studio, Nancy Rubins conjures magic out of the mundane, her wondrous sculptures wowing crowds across the globe. Just don’t ask her why she does it

Words by ELIZABETH KHURI CHANDLER

Photography by CARMEN CHAN

Halfway to Nancy Rubins’ studio in Topanga Canyon, the Uber driver starts to freak out. We are deep into westside wilderness, navigating hairpin curves on a steep, single-lane road that teeters on the edge of a shrub-scattered abyss.

After several forks, we pass through an electronic gate up a lane flanked by oaks and fruit trees to a large studio with garage doors on each side. Inside, a small-scale model from her Monochrome for Austin canoe piece sits in one corner, the bows pointed in different directions, like a star bursting. One of Rubins’ signature drawings is pinned to another wall in billowing waves. Outside, a mob of aluminum children’s play structures forms a huge 17-foot-tall arc that you can walk under. You get the feeling a typical studio with a roof and four walls would impede her fantastical ideas. She needs this perch atop a hill with its wide-open sky to allow her mind to travel, unencumbered.

“Hello!” says Rubins, bounding over, her sparkling blue eyes framed by trademark fringe bangs. She’s dressed all in black with a jean jacket. Her hands are large and useful; you can tell she uses them for a living. “I’m a simple speaker,” the artist warns. And she isn’t wrong. Over the hour we spend together, Rubins avoids talking about the meaning behind individual pieces or her place in the wider firmament that is the art world. “How I contribute to the community?” she asks. “I do it by making art. You know what I mean?” It’s that simple for her. So I don’t take Rubins’ evasiveness as an affront. This is just her M.O.

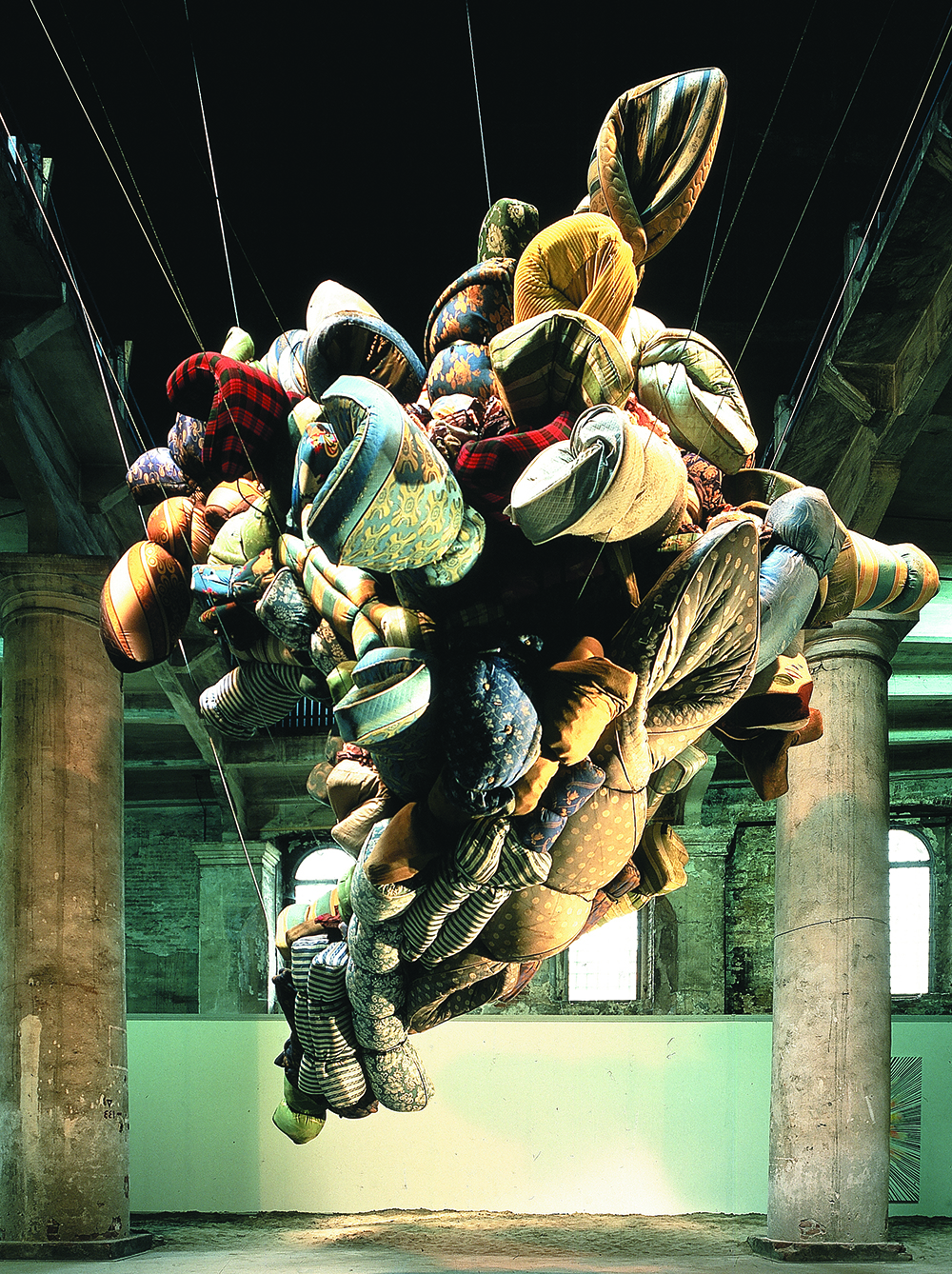

Even though she’s 65, Rubins hustles like a teenager. She’s recently been obsessed with playground figures and garden animals. She finished a major sculpture show in London at Gagosian entitled “Diversifolia,” which featured upside-down clusters of said animal statues, held together by wires; she installed Crocodylius Philodendrus, another pile of larger-than-life versions of the animals in brass, bronze, iron and aluminum, next to Norman Foster’s Gherkin building as part of London’s 2018 Sculpture in the City. She’s just installed a permanent sculpture, Monochrome II, one of her exploding starlike structures made of canoes, at the new Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas. And in November she will be honored at Manhattan’s MAD (Museum of Arts and Design) Ball.

Closer to home, in the courtyard above Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art, her sculpture made of 1,000 pounds of stainless steel and pieces of retired aircraft is on display. (She also has public works installed at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the FRAC Bourgogne in Dijon, France.) Her art is in the permanent collections at the world’s major art museums, from New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery to Université Paris Diderot. To say she’s prolific is an understatement.

From the beginning, Rubins has been playing with objects with a past, amassing vast quantities, piecing them together and turning them into something lively and Lazarus-like. She started out in an industrial building south of Market Street in San Francisco in the late ’70s. In addition to sculpting, she was teaching painting at the San Francisco Art Institute and waitressing. She even started a house painting company to make ends meet. It was a hardscrabble, hectic time. “I would get thousands of dollars of parking tickets,” she says, laughing.

Trawling the Goodwill with friends who were looking for vintage clothing, she eyed some old televisions that cost between 25 and 50 cents a pop. Some 300 TVs later, Rubins started building walls of them in the warehouse she called home. “I wasn’t very happy with them,” she admits. “They never transcended their TV-ness. There was a rigidity and formalism, and that wasn’t really the direction I was interested in going.” When an earthquake hit around the same time in San Francisco, and the walls of her studio were left rippled and undulating, she became fascinated. “In the right circumstances, something so strong and hard and rigid could behave like this fluid, graceful thing,” she says. She turned to cement mixed with expanded metal and then started adding in appliances.

It was in the early ’80s that the art world took notice. Her first public commission, Big Bil-Bored, a giant gunlike structure made from cement and studded with ancient appliances, was voted “Ugliest Sculpture in Chicago” in a radio poll. Rubins was tickled by the reaction. “The client was delighted because it showed his shopping center on the national news,” she recalls. “People went out of their minds.” She pulls up another controversial early work on the computer. Worlds Apart (1982) was a giant, 40-foot-tall, thought-bubble-shaped mass of cement and appliances that was positioned in front of the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C.

Since then, most of her works are tasked by museums or installed in public places after they are created. I suspect that the traditional process of working with multiple committees, getting buy-in, and explaining the meaning behind a work of art does not seem like the way she prefers to do things.

“She’s the ultimate formalist,” says Stephanie Barron, senior curator and department head of modern art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Nancy is interested in formal qualities—the engineering, the balance of the objects. Looking at the sculptures, you have to wonder, ‘Is it going to fall down?’ That tension between the viewer and the sculpture mirrors the tension in the wires that hold up the elements of the sculpture.”

When Rubins moved to Los Angeles in 1982, living on Sixth and San Pedro streets, she started rethinking her work. While some artists might have toned down their oeuvre, Rubins focused on larger shapes, looking for new, exotic forms to play with. She flips through images of works hewn out of trailers, water heaters and airplane parts. “They look like big…swollen…appliances,” she says with intensity. Half of the job, she admits, is tracking down these unusual materials. It’s not a problem. She describes herself as a “tenacious person.”

“There’s always a guy,” she says. “They are happy to see me.” But the rigor of scavenging for retired appliances and the ardor behind their assembly fades into the background when you see the finished works firsthand. The quotidian objects and industrial materials coalescing into large-scale abstract shapes are what can only be described as beautiful cacophonies.

Critics cite the California assemblage tradition and collage as an influence, along with sculptors such as Robert Rauschenberg and John Chamberlain. There’s also a hint of the absurd in her found-object creations, a nod to Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers. These spacelike forms push the limits of what you expect from materials.

Of course, she won’t comment on any influences. Instead she wants to show me the nuts and bolts of how these pieces come to life and queues up a time-lapse video of Big Pleasure Point being built in New York’s Lincoln Center in 2006. After working with airplane parts, Rubins had gotten turned onto boats, thanks to admiring a canoe belonging to her late husband, artist Chris Burden. “I remember saying, ‘Oh, it looks like my airplane parts,’ and he said, ‘You know, it’s made by Northrop Grumman (the aerospace and defense company).’” (Beehive Bunker, a 2006 work of art by Burden, is atop one of the neighboring hills in Topanga.)

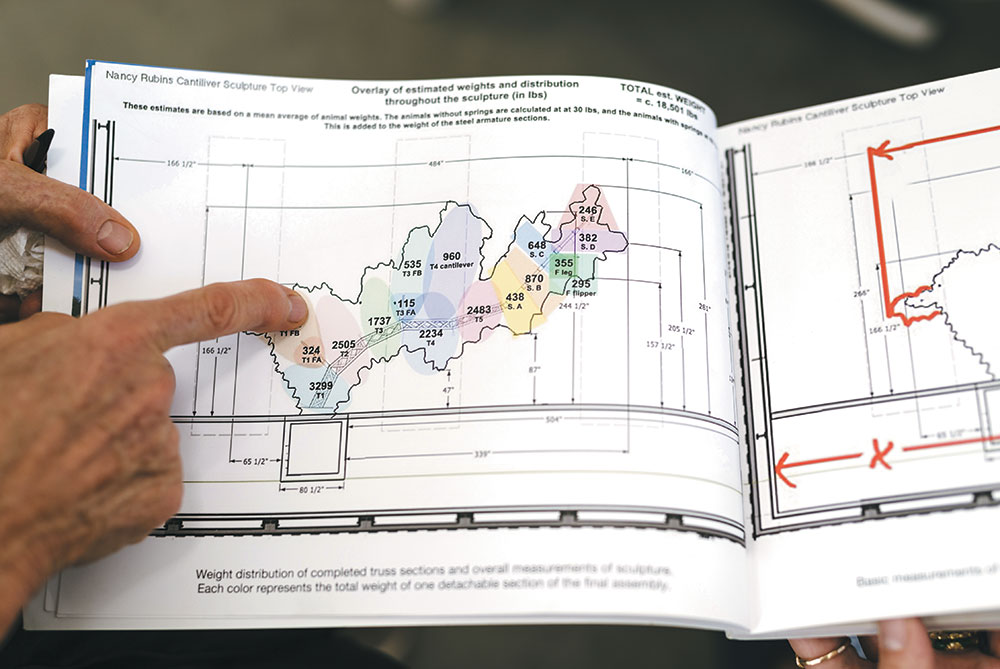

Something clicked and she started playing with the pointy, parabolic shapes. The name Big Pleasure Point came from the rental place where she had picked up the obsolete materials. In the video, which is largely filmed at night, you watch as 60 kayaks, canoes, rowboats, surfboards, windsurfing boards, motorboats, sailboats and even paddleboats are hoisted up and cabled to a 28-foot-high steel armature over a period of one week.

For Rubins, it’s the dimensions of the raw materials that propel her to work at such a scale. “It’s not going to work if you use 10 or 15 of them; you need a lot of them,” she explains. “Abundance has always been in my playbook. And that’s part of what makes California so attractive to me.”

“I have a great engineer,” she adds as we walk outside. Rubins has worked with the same team of five technicians (who wear gear and climb over the sculpture like it’s a big tree) for decades. And she needs them. The pieces are made almost like suspension bridges, with multiple layers of redundancy.

In front of us is Our Friend Fluid Metal, the aforementioned 17-foot-tall arc from her eponymous New York series that glistens in the afternoon light. The cantilevered sculpture seems to hover over the concrete courtyard, casting a long shadow. “You are getting a visual physics lesson in a funny way, you know?” she explains. “You are seeing the exact amount of structure necessary to keep that in space and in place.”

The finished work is so dense and painterly, you get lost inside it. In particular, the works from the Our Friend Fluid Metal series and “Diversifolia” evoke a certain pathos, a childhood gone awry, calling to mind the works of Mike Kelley or Paul McCarthy. With the playground animals, she’s transformed figurative elements into abstraction. “I was kind of concerned about them,” she says, thoughtfully. “They were kind of cartoony, and they are super thick. I’m used to working with airplanes, boats, mobile homes.”

Rubins squints, focusing on the form. “You know what I love most?” she asks. “The tendrils that you see when you stand under it…delicate tendrils that fly out in space above your head.” And whatever else you make of it is totally up to you—Rubins’ orders.