With its permanent sculptures, exclusive guest list, anarchic spirit and apocalyptic setting, Salton Sea’s Bombay Beach Biennale is an experience unto itself

Words by STEPHANIE RAFANELLI

“What would you pack in a suitcase today if you had to leave forever from a world that might never exist again?” performance artist Rachel Libeskind, a young blonde woman in a straw hat, croaks into a megaphone while crouching over a jumble of suitcases in the Sonoran desert dust. On a local resident’s property, a yellow corrugated iron structure is sprayed with the neon pink words: “Toxic Waste,” “Is the Threat Real?” and “Will We Survive?” In the circle of 25 occupied seats that surround Libeskind, a hipster Jesus in a long fur coat sits next to an old woman, her face like cracked sand, blinking into the glare of the Saturday morning sun, absentmindedly holding a limp stick of broccoli.

At Bombay Beach Biennale, all rational thoughts are left behind. This self-described “radical immersive art and culture” takeover has run yearly since 2016 on the eastern shore of Salton Sea—a man-made saline lake in the desert caused by an engineering disaster on the Colorado River in 1905. The abandoned and surreal fringe town of Bombay Beach serves as both inspiration and permanent three-dimensional canvas.

Three hours’ drive southeast of Los Angeles and an hour outside of Palm Springs, this former 1950s resort that once drew Frank Sinatra and The Beach Boys never fulfilled its promise of becoming the California Riviera. Algae bloom caused by agricultural runoff and overpopulation led the introduced tilapia fish to suffocate; at one time, millions washed up on the shores. The sulfurous whiff of decaying flesh on the wind is both the smell of the past and a looming environmental disaster on the horizon.

“This place is apocalyptic. It’s going to be uninhabitable in about 50 years because of the toxic fumes from the dust and the sand. And they will also blow across the coastal cities of California,” says Libeskind, the daughter of architect Daniel Libeskind, master planner of the reconstruction of the World Trade Center in New York.

Each one of Bombay Beach’s 100-odd residents has a different account of the town’s time of death. But some believe that art can be its salvation, in the same way Donald Judd’s minimalist works were to Marfa, Texas. In recent years, artists escaping Los Angeles rents have been buying up shacks here for as little as $20,000. Past the artificial ridge of the berm that shelters the town from the sea is the vast gray moonscape of the beach itself. “Save Me,” implores a red neon sign hovering above the water, erected a few days ago by Berlin-based American artist Olivia Steele.

The beach is an austere and (quite literally) moving gallery space, with the noise of waves and the wind battering your hair. Next to a giant Tesseract light cube by Steve Shigley and an installation of a hand of tarot cards emerging from the sand, stands a silver being—part alien, part android—in a full facial and body stocking, like a futuristic nuclear suit. (This place was once a testing ground for ballistics and a long-term storage place for atomic weapons.) “You think about what this might be like in 200 years,” says Libeskind. “It might be a Chernobyl. People might have to come in hazard masks to see the ruins of art left on the beach.”

And by the circular laws of nature, the town’s death might also be the beginning of something. Still, no one can answer when I ask: the beginning of what? “I think we are bored of seeing art in white spaces,” says Libeskind. “The white box thing was radical in 1955. It’s not been radical for a very long time. It’s over. It’s the last breath of the Larry Gagosians of this world, whose institutions will effectively be museums.” As if by some insider joke, we walk past a food truck selling barbecued bones called Larry G’s.

On its website, the Bombay Beach Biennale announces that its “only agenda is saving the sea.” Counterintuitively, it hopes to raise awareness by running a self-funded festival-that-isn’t-a-festival. “If it’s about keeping the spirit of creation pure, then I can’t imagine a better format than not trying to sell anything to anyone,” says co-founder Stefan Ashkenazy, co-owner of West Hollywood’s art-driven Petit Ermitage hotel.

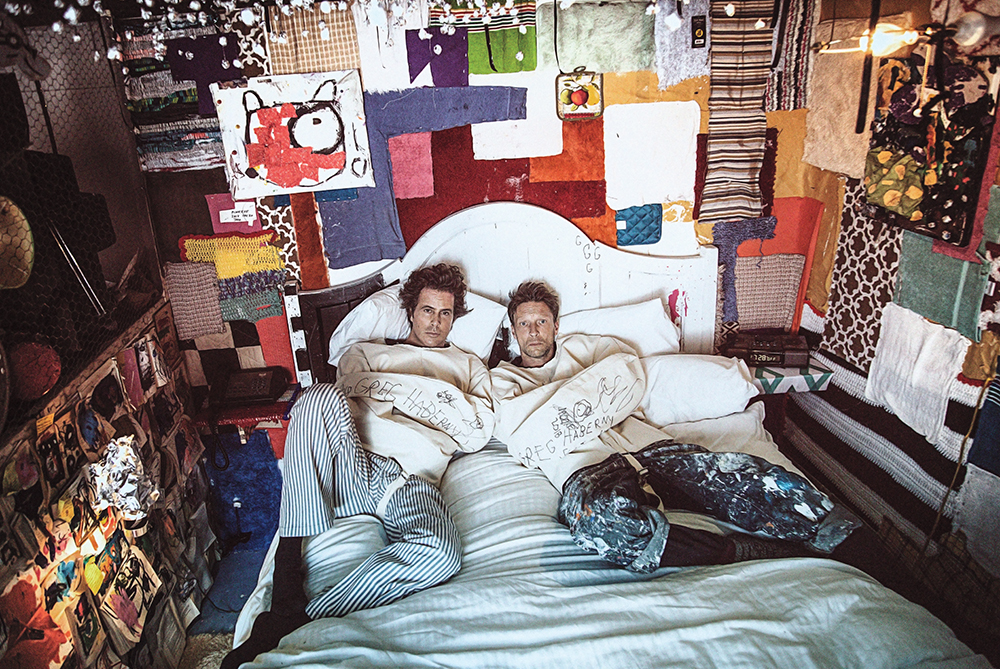

Life and art merge on the avenues of Bombay Beach; the square mile of derelict shacks owned by locals are indistinguishable from the houses bought by the Biennale and gifted to artists to be turned into year-round installations, which include The Hermitage Museum designed by artist Greg Haberny, The Bombay Beach Opera House by artist James Ostrer, and The Bombay Beach Drive-In Theater, an outdoor film venue furnished with dilapidated cars and boats.

Life and art merge on the avenues of Bombay Beach; the square mile of derelict shacks owned by locals are indistinguishable from the houses bought by the Biennale and gifted to artists to be turned into year-round installations

Invitees aren’t allowed to camp in town, so many check into a nearby RV park called the Fountain of Youth Spa, or commute from hotels in Palm Springs. Upon arrival, tickets are checked at The Ski Inn, where guests are given wristbands—signifiers that feel unnecessary in a realm where barricades are nonexistent. The evening ballet and opera performances (annual weekend highlights) are included on the official, if skeletal, schedule, but most happenings are fluid: The best way to experience the event is to wander and let it happen to you.

If anything, Bombay Beach is the anti-biennale of the Venice kind. Co-founder Tao Ruspoli, a Joshua Tree-based filmmaker and the son of Italian bon vivant Prince Alessandro Ruspoli, admits that the “Dadaist, surreal, absurdist” group art-town installation hopes to “take the art world down a notch or two and Bombay Beach up a notch.” (His friend Bella Freud, daughter of Lucien, designed the logo.)

If anything, Bombay Beach is the anti-biennale of the Venice kind.

“It’s hard to feel that you are part of something anarchic with regulation and rules,” says Ashkenazy, dressed in a black velvet floral kimono and rose-colored sunglasses. “It’s also part of the spirit of this town. The people here are real renegades…The art world is a pretentious thing, and there is a joy in poking fun at it—and ourselves. The artists that come out here have the ability to not take themselves seriously.”

Tickets are limited to 500 and given away free to “those who are curious enough to find their way in,” says Ashkenazy. Food and drink is free and provided by the organizers through donations, though they encourage guests to bring their own provisions and invite locals to partake in vending, too. “The festival is the best thing that’s happened to this town for years. Some of the people round here don’t want it. But it’s brought life back to us,” says Geordie, a weather-beaten former snowbird who settled here a few years ago and sells earrings made of guitar picks.

This meeting of cultures—diehard residents, weekenders from Silver Lake, L.A. artist transplants, members of the European beau monde—shouldn’t work, but somehow does. “There is a strange symbiosis between the locals and the new artist community; one cannot exist without the other,” agrees Ashkenazy.

Each year, the Bombay Beach Biennale works with the local community to earn their support for the festival and to collaborate on the planning of events. Yet Ashkenazy, Ruspoli and a third co-founder, Johnson & Johnson heiress Lily Johnson White, now own more and more of the town. Ashkenazy won’t specify exactly how much. Each founder loosely curates their own properties. The resulting art is left for the town to use. The Bombay Beach Drive-In stays open all year long with a permanent projector and soon-to-launch website where locals can vote for the movies shown. There is currently a vacant position for town projectionist.

Ashkenazy, who “grew up surrounded by art and artists,” has good qualifications to be an art patron. His great-grandfather brought Henri Matisse to Russia, his Polish-Jewish grandfather Izador was a friend of Joan Miró and a collector of Monet, Gauguin and Picasso. His uncle Arnold was a friend of Jean-Michel Basquiat, and along with his father, Severyn, owned one of the largest art collections in California. “Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, my father went bankrupt [in the 1980s] and lost quite a bit. I got to learn from that experience and seeing it all go away. It allowed me to create my own relationship with art.”

Born in L.A., Ashkenazy moved to China when he was 17, where, he explains, he studied and created “experiential works” for Shanghai nightclubs. After a 12-year career in aerospace defense, living between Russia and China, he returned to L.A. and bought a rundown hotel in 2014 with his brother Adrian, which they transformed into Petite Ermitage. He hung the walls with his own collection of art, comprising Dalí, Miró, de Kooning, as well as several pieces that once belonged to his father, which he reacquired at auction. “But for me, hotels were this ultimate form of immersive art.” (Suite 406 of the hotel has been transformed by post-contemporary artist Greg Haberny into a habitable art installation.)

So is Bombay Beach Biennale one living, breathing art installation? Is it post-contemporary art?

Ashkenazy saw the same potential to claim what is lost at Bombay Beach in 2014. Ruspoli had already bought property here, and Ashkenazy’s then-girlfriend, Arwen Byrd, had written a zombie apocalypse movie set in Bombay Beach. Together with Johnson White, their idea evolved into an art event with the “collective, communal spirit” of Burning Man. So is Bombay Beach Biennale one living, breathing art installation? Is it post-contemporary art? Environmental art? A twisted take on traditional art fairs? Is it the culmination of a new site-specific Californian desert art movement begun by the likes of Noah Purifoy in Joshua Tree? Ashkenazy says he has no idea.

It’s Saturday night and the town is filling up now with more moustachioed men in fur coats, and women in ball gowns or top hats—there cannot be more than 300—ready for the Bombay Beach memorial parade: a mass town march to the beach holding pictures of late local legend Roger Herbert, who bears more than a passing resemblance to the spiritual leader of an Indian ashram. The main event of the evening is a performance of choreographer Benjamin Millepied’s “Closer” and Sebastian Kloborg’s “Credo:1877” by San Francisco Ballet principal dancer Maria Kochetkova and Kloborg at The Bombay Beach Opera House. The tiny, blue wooden Opera House, with doors that open out to a stage and flip-flops on the wall giving the optical illusion of bricks, was created by artist James Ostrer. The walls are hung with nightmarish photographic portraits of humans clad in raw animal flesh, mounted on floral mattresses. The only single theme of the work produced at Bombay Beach, it seems, is that it refuses to frame itself as high art without undercutting itself.

“The audience is so diverse and so accepting here. It’s classless, inclusive,” says L.A.-based ceramicist and sculptor Yassi Mazandi on Sunday morning when I meet her at The Bombay Beach Institute of Particle Physics, Metaphysics & International Relations—a gallery and performance space where last night’s revelers are playing boules. A few days ago, she erected her first giant sculpture, Nine, on a plinth in the empty patch of grass of the Bombay Beach Botanical Gardens imagined skeletal structure of a flower made from 250 pieces of foam glued together, painted and sanded down by hand. The 56-year-old says it isn’t only the challenge of working out here with only the bare essentials, battling against the environment that has brought her artistic process to a new place. It’s also the spirit of the town. “It’s special not because it’s fleeting but because it’s struggling to survive. People have chosen to live here. But some of the people don’t want to be found.” Not all the residents are happy about the festival. “I’m leaving my piece here. I have no idea if someone will graffiti it or set fire to it.”

But, like the other artists, Mazandi says the biennale is “the beginning of something that has extraordinary potential.” She continues: “California has a habit of starting something, whether it’s herbal life or some crazy diet or surfing or Botox. There is something going on with how art is re-evolving, of how it is experienced. It’s about going into an environment that fully encompasses you. There is a movement.”

“There is something going on with how art is re-evolving, of how it is experienced. It’s about going into an environment that fully encompasses you. There is a movement”

Thomas Linder, an understated 32-year-old fiberglass artist from Downtown Los Angeles with a Jack Kerouac aura is less convinced about the value of the biennale. “It’s just kind of this Burning Man vibe in a way, people that normally sign up for music festivals coming just because they want to be entertained. It needs a proper curator; you need to curate the culture and then the right people come, rather than the other way around.”

And are the organizers of Bombay Beach Biennale going to harness that? “There really is no master plan for what we are doing here. We are going to keep it amorphous,” Ashkenazy muses. His main goal for next year is opening what he dubs “a very strange hotel called The Last Resort—the Hôtel de Ville of Bombay Beach. It’s going to be a playground for the different artists to build wild and weird rooms with extraordinary amounts of freedom,” he explains. “So many people in the hotel business are having a race over who is the coolest and the most chic. I’m excited to run a race that no one else is competing in: the one to the bottom. Having the first hotel with zero stars.”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2018 Men’s Edition of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.