A surreal new show presents the Oakland photographer’s magic-tinged Californian landscapes

Words by MELISSA GOLDSTEIN

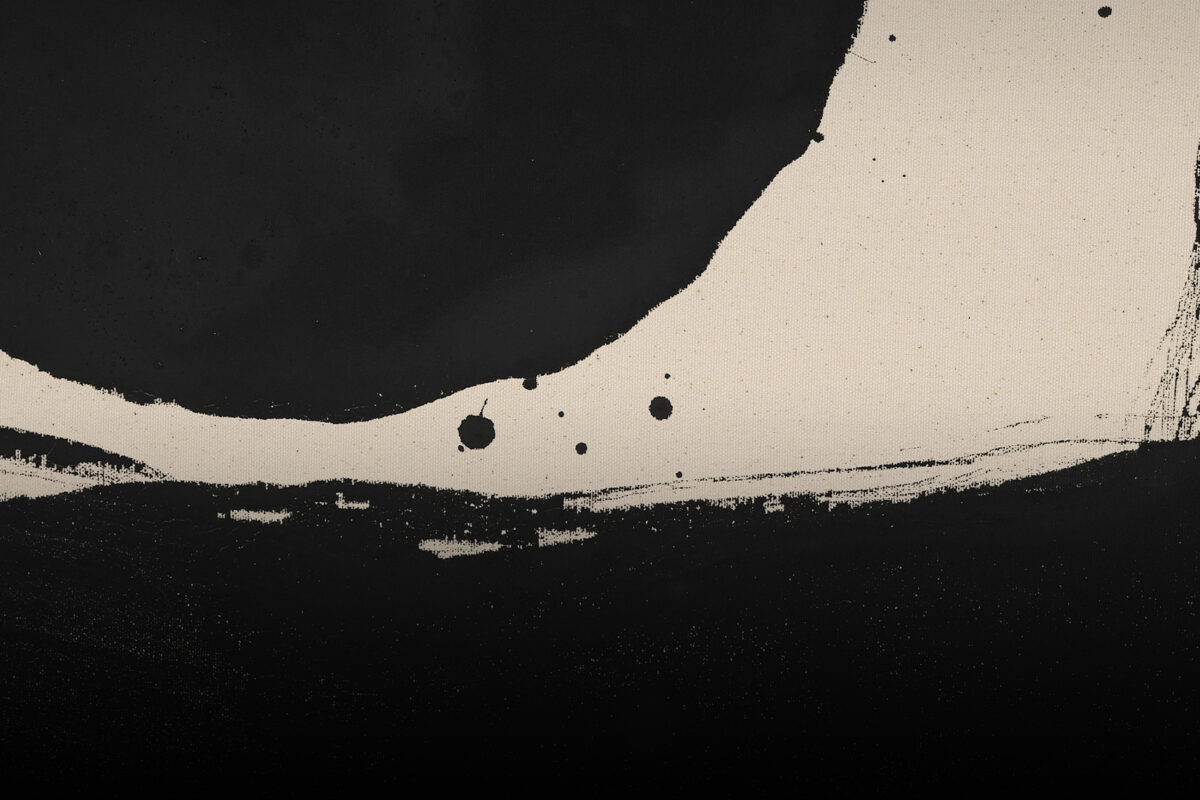

“I’ve always been envious of painters’ abilities to shift reality in whichever direction they choose,” says Oakland-based photographer Terri Loewenthal. That fascination underpins Loewenthal’s “Psychscapes,” a series of magic-tinged, hallucinogenic images the artist first began experimenting with in 2013, eventually honing her concept four years later while shooting in California’s Eastern Sierra. The area’s otherworldly topography lent itself to her signature technique, in which she painstakingly tweaks a single exposure by overlapping multiple vantage points of the 360-degree surrounding environs and applies filters to shift colors.

“It’s very much about using the landscape as raw material instead of subject,” explains Loewenthal, who has exhibited close to home at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco and internationally at Paris Photo at the Grand Palais. In June, selections from “Psychscapes” in addition to an editioned mural she shot during a hike around the Twenty Lakes Basin near Yosemite National Park will be included in San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art’s 12-person group show “Surreal Sublime,” a multimedia exploration of abstracted takes on nature. “Surreal Sublime,” June 22-Sept. 15. 560 S. First St., San Jose, 408-283-8155.

How did you come up with the concept/inspiration for “Psychscapes”?

When I had the idea for these images, the only thing I knew is that I wanted to shift the natural world just enough to make it surreal, but still inviting. Nature has always been my refuge. When studying landscape, even before I discovered my current process, I was rarely drawn to make a literal document of nature. I’ve always been more interested in depicting the palette of a place than the place itself. The relationship between colors is endlessly fascinating to me and initially, I mostly daydreamed about toying with that dynamic.

My desire to push the boundaries of photography is also partly a reaction to the ubiquity of photographs today. I’ve been taking pictures for a long time. A few years back, I had a bout of feeling bored with making imagery and it caused a mild identity crisis. The only cure I could find was to make images that I was genuinely excited to look at, which meant they had to look completely different than anything else. I needed to deliberately engage in a process of discovery in order to deepen my relationship with what I was seeing.

Was there a lot of trial and error with honing the technical process you use for creating these images?

Absolutely. I experimented for years, attempting to find a process that works with the natural beauty that already exists. My work involves composing reflections of the 360-degree landscape surrounding me and using filters to shift colors. Each image is a single exposure; all of the layering and color-shifting happens optically. I’m not sure I’d refer to my earlier attempts as “errors,” but it’s fair to say that my initial idea of shifting color alone wasn’t enough. When the image was just a variation of the natural world, it didn’t transport me. It wasn’t until I stumbled upon the layering technique that I felt like I was making another landscape altogether — a place I really wanted to be. I just kept pushing until I felt the rush. Anyone who’s ever made anything knows about the rush. It doesn’t always happen, but when it does, I no longer question what I’m doing, or why I’m doing it — it’s just absolutely meant to be. That’s when I knew I’d finally found it.

How would you describe your work prior to this series?

Appreciation for the free spirit has always been a catalyst in my work. I’ve long been interested in making an image from a feeling, but before this project, I might have been more likely to shoot people in the process. A lot of my previous work represented a sort of serendipity, a feeling of being in the right place at the right time, often conveying my own community in intimate spaces or in the landscape.

What appealed to you about shooting in the Eastern Sierra?

It’s not the California most people have in mind. You see the neon blue Mono Lake from above as you drive towards it, and there are no rivers or streams flowing to or from it. Against a neutral desert palette, it doesn’t even make sense. The Eastern Sierra expanse is ripe with mystery and geometry, all of these granite building blocks, which I use in my work. Truth is, though, I’ve shot all over California.

How do you think your work’s meaning may change or be impacted when it’s showcased alongside the other landscape works in “Surreal Sublime”?

The participating artists explore the historical genre of landscape art with abstracted and dreamlike interpretations of nature. A few others in the show use photographic techniques, but I’m the only one who is physically immersed in the actual landscape during the process of making the work. For this reason, I’m curious to see whether or not my work feels “real” compared to the others — ironic? I intend to present a vision of the natural world that extends beyond its economic and recreational value, illuminating possibilities of spiritual connection and transcendence. Our current political reality includes a government unwilling to confront ecological collapse and a president who is actively deaccessioning public land. My hope is that these images help preserve the wildness of our open spaces by heightening and newly envisioning that wildness.

What are you working on now?

I had the idea for these images years ago, but I’ve only recently begun to pull them off. There is still so much experimentation to be done with my optics, and so many new places to visit. I just started exploring other states in the West: Oregon, Arizona and Utah.

Do you think you will continue to use the “color collage” process you used for “Psychscapes” in your future work?

Color plays a huge role in my drive to create these images, so maybe? I’ll never stop experimenting, and I’ll know the next thing when I see it.

Feature image: Psychscape 90 (Whale Peak, CA), 2018, by TERRI LOEWENTHAL.

This story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of C magazine and has been updated as of June 14, 2019.