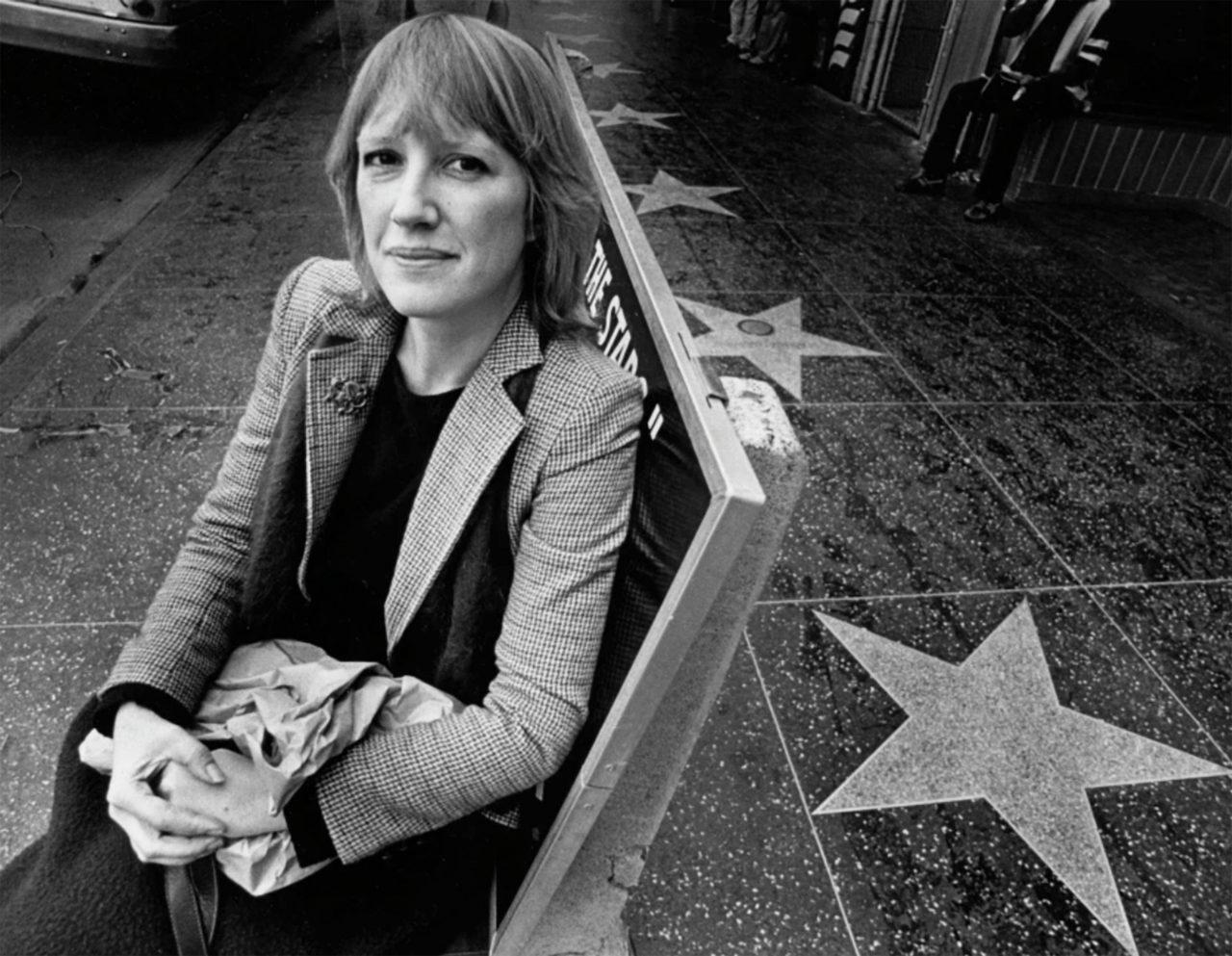

The chronicler of Los Angeles cool and the city’s curious creatures was a voice of her generation

Words by ALESSANDRA CODINHA

Eve Babitz was not famous in the way that people in Los Angeles are usually thought to be famous — which is to say, globally, and with a box-office score attached. But she was a pivotal person in the mythology of the city (the fun parts, anyway), and she would have told you that was even better. Babitz, who died in December at age 78, was a rare breed: a born observer who was also a scene-stealer; a genius writer who moonlighted as an It girl; the sunbaked bard of the city’s hedonistic creative class and its cavalcade of curious creatures; an inveterate Angeleno in love with her sexy, smoggy city.

“In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz. It’s usually Eve Babitz”

Earl McGrath

Babitz wrote in her 1974 essay collection Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, The Flesh, and L.A. that she got near enough to fame to “smell the stench of success,” and she wasn’t convinced: “It smelt like burnt cloth and rancid gardenias, and I realized that the truly awful thing about success is that it’s held up all those years as the thing that would make everything all right.” Her father was a baroque musicologist and a violinist with the Twentieth Century Fox studio orchestra, and her mother was an artist; family friends were illustrious and generous and included the likes of Edward James, Eugene Berman, Jelly Roll Morton and Marilyn Horne. Igor Stravinsky was her godfather, and future starlets and the children of L.A.’s success stories peopled her classes at school. “I think I’m going to be an adventuress,” she wrote that she said as a child to her mother. “Is that all right?” It was. Babitz developed early, and she didn’t miss much. At 20, she wrote to the novelist Joseph Heller: “Dear Joseph Heller, I am a stacked eighteen-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer. Eve Babitz.” That was it. That was the entire message. Heller introduced her to his editor. It didn’t result in anything much, but it sure set the tone.

All this might sound glamorous — and it was. But Babitz was an L.A. girl who grew up idolizing Marilyn Monroe and Colette: She saw the structures that glamour buffeted, the people who used it and the people who benefited from it, and she knew that glamour wasn’t the end of the story. She took beauty seriously as a topic. “In most high schools, you learn social things along with the rest of it,” she wrote in her first book, 1974’s Eve’s Hollywood. “In mine, I learned irrevocably that beauty is power and the usual bastions of power are powerless when confronted by beauty.” This was partly because her former classmates included bombshells Linda Evans, Tuesday Weld and Yvette Mimieux, and partly because, as she’d be the first to tell you, she wasn’t an idiot.

Los Angeles Times

Babitz understood the importance of surfaces, of scenes, of the right scripted line or styled shag, and her effect on the Los Angeles scene of the 1960s and ’70s went deep. She introduced Frank Zappa and Salvador Dalí, she styled Steve Martin in his first white suit, she designed rock album covers for Buffalo Springfield, the Byrds and Linda Ronstadt. And when she became a writer, in her late 20s, she also became a full-throated defender of L.A., laying waste to East Coast character assassinations of the city as a cultural wasteland.

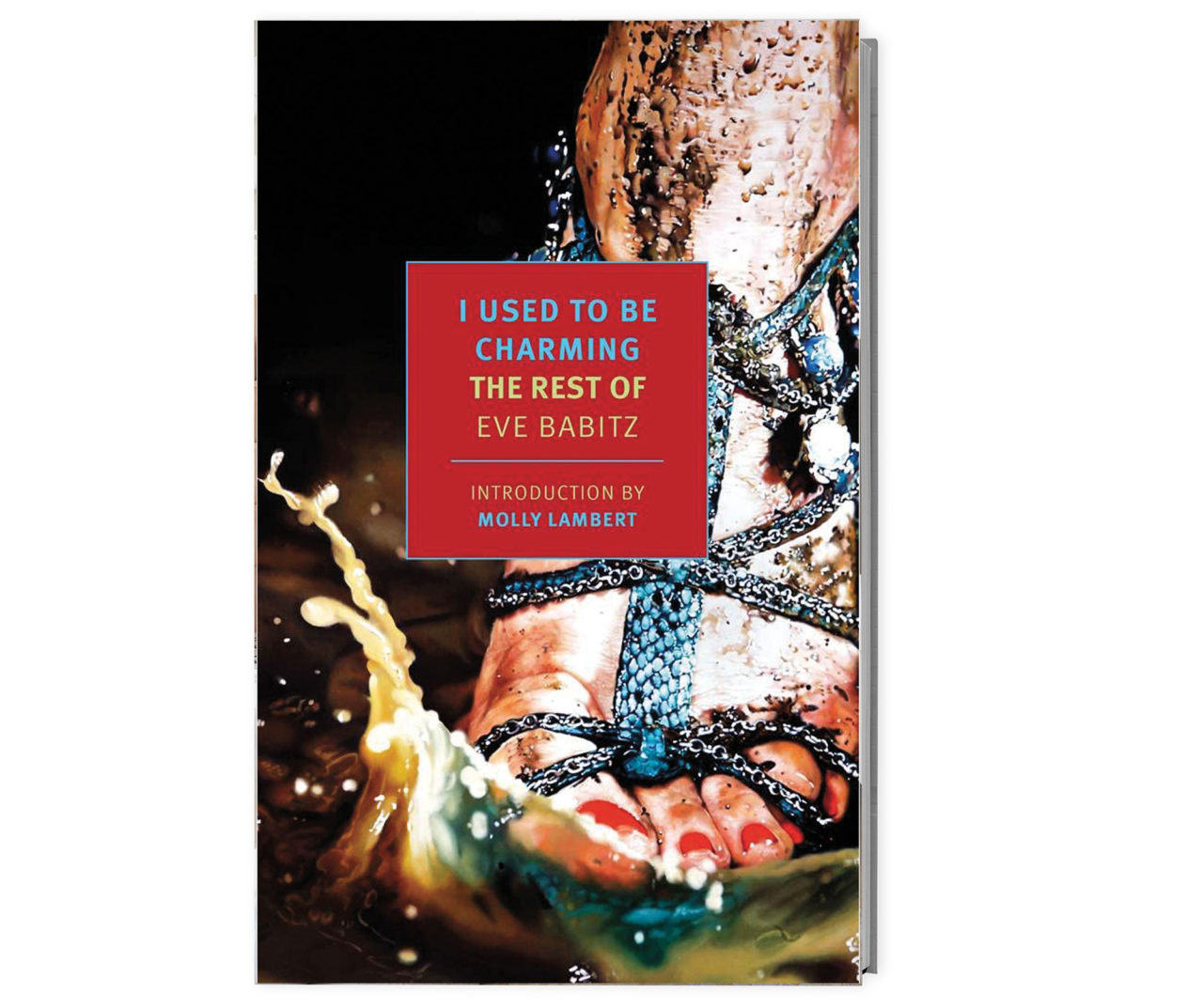

Babitz was published in titles like Vogue, Esquire and Rolling Stone, the latter with the help of Joan Didion, another Californian genius whose legacy is inexorably tied up with where she was from. (Though if Didion, in her extreme thinness, cardigans and perfect sentences, was aiming at surreptitiously blending into the background of the scenes she covered, the Rubenesque Babitz, in her short skirts and shag haircut, was the life of the party who also somehow managed to remember the most minute details the next day.) Babitz turned out a series of thinly veiled novels and essay collections — Eve’s Hollywood; Slow Days, Fast Company; Sex and Rage; I Used To Be Charming: The Rest of Eve Babitz — chronicling the beautiful and the powerful and the strange and the self-possessed with unfailing wit and shameless vigor, and nearly always with her beloved Los Angeles as the setting. “As Duchamp himself said,” she later wrote, “it is the spectators who make the picture.”

“It takes a certain kind of innocence to like L.A., anyway”

Eve Babitz

In her New York Times obituary, the paper of record notes that in her extensive dedication to Eve’s Hollywood, Babitz thanked “her orthodontist, her gynecologist, the Chateau Marmont, freeways, sour cream, Rainier ale (an aid to losing her virginity) and ‘the Didion-Dunnes, for having to be what I’m not.’” That last part was typical Babitz, a little catty, a lot heartfelt. It was also true: The Didion-Dunnes were respected East Coast-aligned journalists and intellectuals known for their laser-like precision. Babitz’s style was looser, broader, a party to which everyone was invited, if they could make it through the jungly murk and woozy miasma of the 1970s Los Angeles scene to where the action really was. And why not? “Because we were in Southern California — in Hollywood, even — there was no history for us,” she wrote in I Used To Be Charming. “There were no books or traditions telling us how we could turn out or what anything meant.”

For a while that meant erotic entanglements that proved Babitz to be as seductive as the slow pace of the city she championed. She had taste: Some of these partners included Harrison Ford, Jim Morrison, Ed Ruscha, Paul Ruscha, Stephen Stills, Warren Zevon, Annie Leibovitz and Steve Martin. As Earl McGrath, former president of Rolling Stone Records, famously put it: “In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz. It’s usually Eve Babitz.” And so it is not altogether surprising that despite her myriad talents as a writer and a visual artist, for a long while her most indelible cultural output was a Julian Wasser portrait of her nude, playing chess with Marcel Duchamp. (She later said she posed for the photo to piss off her married lover, Ferus Gallery founder Walter Hopps, who hadn’t invited her to a scene-y Duchamp opening.) She got an agent, she moved to New York, she worked a little, she came back. Nowhere made as much sense for her as L.A. “It takes a certain kind of innocence to like L.A., anyway,” she wrote in Eve’s Hollywood. “It requires a certain plain happiness inside to be happy in L.A., to choose it and be happy here.” And later, in Slow Days, Fast Company: “I long for vast sprawls, smog, and luke nights: L.A. It is where I work best, where I can live, oblivious to physical reality.”

Obliviousness wasn’t always a positive. After a fallow period in the late ’80s and early ’90s, she nearly burned to death in 1997 when she accidentally dropped a lit cherry-flavored Tiparillo on her lap while driving. The effects of the third-degree burns, which covered her body from the waist down, cemented her desire to avoid the limelight. But all the while, she was being rediscovered by a new generation, championed largely by young women who recognized something fierce in the funny girl with the great rack and the beautiful prose, the sex symbol who refused to be a sex object rather than the subject of her own story. “It used to be men who liked me,” she later joked to Vanity Fair; “now it’s only girls.”

Babitz remained mostly in retreat for the remainder of her life, though she released a few more essays, most notably the titular piece from I Used To Be Charming in 2019, in which she detailed the cigarillo accident and her recovery in her own trademark fashion, a tale both wryly recounted and brutally gruesome, unfurling before the glowing backdrop of Los Angeles. It wasn’t quite the Hollywood ending that anyone would have hoped for, but it fit some versions of the script: A writer uniquely steeped in the champagne fizz of Hollywood knew what things were like when the bubbles went flat. (She had often said — and at least once written — that she was surprised to live past age 25, let alone 50.) “That strange mixture that’s always been a major part of Hollywood — self-enchantment mingled with the ever-present fear of total disaster (earthquakes, fires, random murders) — lies beneath the physical reality of Hollywood,” she wrote in 1993’s Black Swans, “which sometimes looks too good to be true, as though we must have sold our souls to the devil for all those swimming pools and orange trees and young hopefuls basking in the sun.” She wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Feature image: Courtesy Mirandi Babitz.

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.