A group of cash-rich former employees of the $50 billion ride-share company are convinced they can replicate that same success on their own

Words by BRADLEY SPEWAK

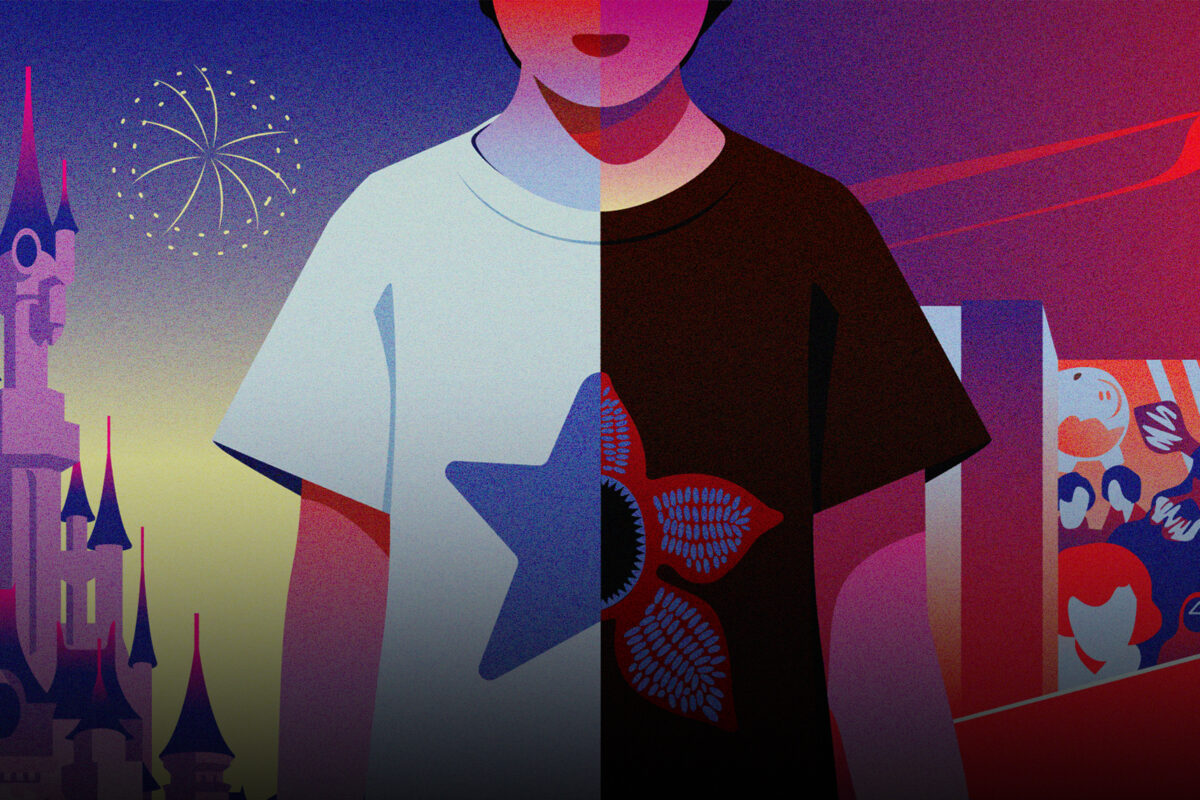

Illustration by NEIL WEBB

When William Barnes left Uber in 2017, he was exhausted. “[Almost] six years is a long time at such a fast-growing company,” he says. “It felt like the right time to make a move.” A longtime British transplant living in Los Angeles, Barnes, 40, joined the San Francisco-based ride-hailing upstart as one of the first 50 employees back in 2012. He launched the service in L.A. and ended up managing operations across several states as the West Coast regional manager.

It was a harrowing ride. Around the time he left, Travis VanderZanden, another Uberite, had recently exited and hatched a new plan: Bird, now arguably California’s most omnipresent scooter startup.

Barnes, flush with cash from his Uber stock, was one of Bird’s first investors. VanderZanden would soon go on to raise a huge sum of money from former colleagues and blue-chip investors even though the company, which is valued at $2.5 billion, has been hamstrung by many of the same labor and regulatory problems that have plagued Uber.

Barnes and his former Uber counterpart in New York, Josh Mohrer, began informally organizing Uber alumni via texts, Slack, Facebook, LinkedIn and occasional meetups. The group has now grown to more than 1,500 people. Last year, Barnes and Mohrer formalized the investing side of that community with the creation of Moving Capital, a syndicate of about 200 former Uber employees with enough cash to dive into startup financing. So far, they have backed 29 new ventures, including Bird’s rival, Lime; luxury email provider Superhuman; and San Francisco’s Standard Cognition, which is developing systems to supercharge the cashier-less checkout revolution started by Amazon Go.

Many of Moving Capital’s investees have also been introduced by former colleagues. According to Barnes, the explosion of activity from the Uber diaspora, both as founders and investors, is thanks largely to how controversial founder Travis Kalanick ran the company. He would send employees to new cities and demand they work miracles. “He expected the city team leaders to act as CEOs,” Barnes says. “Where else would you be given the responsibility to build a team of thousands or hundreds of people, manage a balance sheet, put out fires every day, deal with the mayor, the local taxi authority, the press and solve a unique set of regulatory issues?” The result: hundreds of refugees from Uber — a once-in-a-generation success that in a decade went from nothing to a $50 billion global tech behemoth — who are convinced that they can replicate that success on their own.

There is also a lot of money riding on the belief that this group has the best chance of producing its version of the Paypal Mafia, the moniker given to Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Reid Hoffmann and other former executives from the online payment giant who went on to start even bigger companies. Several of Silicon Valley’s top venture capital firms, from Andreessen Horowitz to Redpoint Ventures, have snapped up former Uber executives on the belief they will be able to spot the next big thing.

Fraser Robinson, the London-based former head of business development for Uber in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, agreed the company experience attracted — and forged — a certain type of person. He says, “If I had to pick one word that defines what they were looking for and optimized for in people at Uber, it’s hustle.”

Jeremy Lermitte spent six years working at Uber: first in New York, where he distributed iPhones to cab drivers to convince them to use this new app no one had ever heard of, and then in San Francisco, where he joined the growth team. The 31-year-old left in late 2018, and in the spring launched RedCircle, a podcast hosting company, which received backing from several former Uber employees. In fact, his five-person team is all ex-Uber. Why? “When you’re forged in the same fire, you understand one another and the same ideologies and processes to build a great product,” he says.

“If I have like a $20 million exit, it’s probably not that interesting. I might have made more than that just investing”

Former Uber employee

What is not appreciated by the masses of former Uber employees now populating the startup landscape is that Uber was an unprecedented, and probably unrepeatable, ride. And Robinson, 46, warned that many of his ex-colleagues may be in for a rude awakening.

“A lot of those younger people have had no other experience, other than Uber. They have no idea how hard the world really is,” he says. “They ignore the fact that they had almost a perfect product, they ignore that they had unlimited budget.”

Indeed, for those who got in early enough, simply hanging on for four years (the period of time after which they could take possession of all of their stock options) imbued them with a skewed sense of confidence, and of what success looks like.

A 34-year-old former employee who spoke on condition of anonymity repeatedly referred to the “little bit of money” he made from his time at Uber. When pressed, he acknowledged that the sum was several million dollars — enough to not have to work, but not enough to impress his former colleagues. Instead, he is aiming to build a multibillion-dollar empire with his new company. He says: “If I have like a $20 million exit, it’s probably not that interesting. I might have made more money than that just investing. [I] want to try to do something really, really big, [and] having money does allow you to swing kind of bigger.”

Dmitry Shevelenko, a former business development executive, left Uber last summer. He cast around for his quintessential “big idea” until he found it: training wheels. His Mountain View startup, Tortoise, wants to fit a tiny set of training wheels to scooters, along with an inexpensive radar chip, front-facing cameras and a microprocessor that will combine to turn today’s rental scooters into autonomous vehicles capable of being summoned to their next job. The cost for each conversion? About $100.

His ambitions stretch far beyond turning Bird’s fleet into ghost scooters, however. Tortoise, he argues, could “change the world” because the technology could be applied to other vehicles: electric bicycles, even delivery robots. “We’re doing for the world of physical things what the Internet did for the world of digital things, which is to make the transfer costs of an item [close to zero].”

Not everyone will be celebrating the blooming of so many Uber seedlings. The company, after all, was blasted for its Cro-Magnon culture, led by Kalanick, which was allegedly hostile to women and a desert of diversity. Could all of these spinoffs just revive the toxic bro-topia that ultimately forced Kalanick to step down?

Blaine Light thinks not. In 2017, the former senior operations manager launched Qwick, a platform for service industry professionals (bartenders, cooks, dishwashers) to find shifts in real time. Staff at his new company is nearly 50 percent female, and diversity, he asserts, is a primary focus. Of his time at Uber, he says: “Sometimes in hypergrowth, those issues can get away from you.”

Perhaps the best-case scenario is that the Uberites seeking to rekindle the magic in new industries have learned from the mistakes of the past. Shevelenko explains, “Former Uber employees believe that Uber is more impactful than any other group of people in the world, so they can’t imagine just being part of something. It has to be something where they’re playing a really big role that could have a massive impact on the world. Landing a senior director role is not going to get you cred.”

This story originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2019 Men’s Edition of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.