In her new memoir, Ambassador Nicole Avant recalls life lessons instilled by her music mogul father and beloved mother

Photography courtesy of NICOLE AVANT

Ambassador Nicole Avant.

“I still remember my thirteenth birthday party. I’d wanted to go roller-skating at Flipper’s with a group of friends, as any thirteen-year-old Angeleno might. I didn’t think it was that much to ask . . . until my dad had other ideas. “Duke Ellington’s Sophisticated Ladies is playing at the Shubert Theatre,” he said, “so that’s what you’re doing for your birthday party. Gregory Hines is in it, and Duke’s grandkid Mercedes, too. So you and your pals are going, end of conversation.”

This wasn’t bloody-mindedness on his part, though it might have felt that way to a thirteen-year-old. Instead, it was a reminder that when it came to honoring my culture, and culture generally, it was important to realize that I wasn’t growing up in a vacuum. Roller-skating to “I’m Coming Out” by Diana Ross might have seemed like more fun, but the chance to hear the music of Sir Duke and witness the genius dancing of Gregory Hines?

I knew how lucky I was. When my father was a thirteen-year-old, he was kicked out of his house for defending his mother from his emotionally and physically abusive stepfather and found himself alone riding a train to New Jersey to escape his tough family background — no Shubert Theatre for him back then. When Duke Ellington was in the eighth grade, he was told that if he found himself next to a white woman in a theater, he was to behave his best because he was representing his race. My father didn’t need to tell me that story to underline what Duke Ellington went through; he just made us listen to the music and skip roller-skating so that we, too, could be “sophisticated ladies.” There was a whole world of struggle and a lack of opportunity that I needed to know about and to use to fire my own future, because if you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.

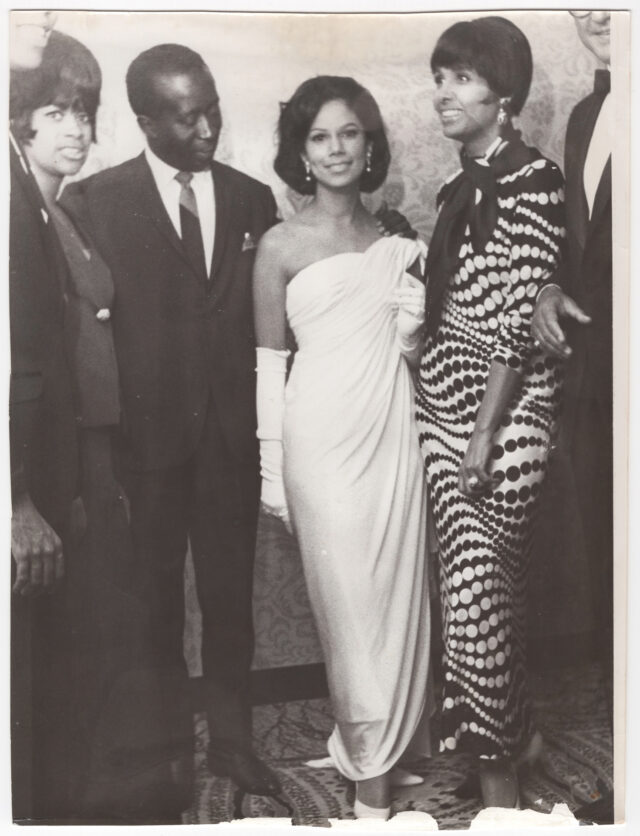

The author’s parents, Jacqueline and Clarence Avant, with Lena Horne in 1966.

It wasn’t just my father who made sure I knew my history, cultural or otherwise. My mother was steeped in history, too — though the lessons she learned from history, and that she imparted to me, weren’t always the ones you might imagine. I remember one year we brought permission slips home because our school wanted to show us a movie about the death of John F. Kennedy, and some of the scenes would be potentially harrowing for kids. I was probably around ten years old, so this was the late seventies, and back then, parents were a bit different from how they are now — tougher perhaps, less helicopter-y, and certainly more willing to let their children be exposed to the realities of an often-cruel world. There were maybe two kids in my class who weren’t allowed to watch the movie (I dread to think how many would be kept away now), but I remember how fervently my parents wanted me to see it, especially my mom. The movie itself made a huge impression on me. I remember going home and running in to see my mother in our living room.

“I can’t believe how Jackie O tried to grab the remains of JFK’s brain!” I exclaimed, before I’d even said hello. That moment, to me, was the most incredible one of the whole film — to love someone so much that you’d do something so unfathomable. “I can’t believe this happened,” I added, which is something I always seemed to say about the history I was learning. My mother saw it differently. “Nicole,” she said, “you have it all wrong.” I was confused. “But Mom, she actually tried to save parts of his brain.” “Instead of being in disbelief, Nicole, or focusing on the gruesome details of the tragedy, you need to say, ‘I can’t believe all these great things these people did. I can’t believe the way they lived for other people. I can’t believe that they got up every day to serve.’”

That was why my mother had signed the permission slip in the first place — not so her daughter could be horrified by an assassination, but rather so that she could learn the lessons of the life lived by whatever person was involved, be it President Lincoln, JFK, RFK, or Martin Luther King Jr. The incidentals of their death were just that — incidental. What mattered was the life they’d lived. I would think about this lesson — that life is what matters, not the manner of a death — many times in the months after my mother’s passing. It gave me great comfort, and still does. My mother understood that no one knows how life will end, no one knows what or how long a future is, so the only thing to do is to live fully, to expand one’s horizons as long as one has breath to do so.

And when someone is gone, to focus on the good, not the loss. Excerpted from Think You’ll Be Happy (HarperCollins, $28.99).

Feature image collage, clockwise from top left: Nicole Avant with Barack Obama, 2007. Muhammad Ali with Avant, her mother, and her brother Alex, 1992. Bill Withers with Avant at his wedding reception at her house, 1973. Avant with her mother and Grandma Zella, 1972. Young Avant.

TAYLOR HILL wears GIVENCHY jacket, shirt, and jeans; BUCCELLATI bracelet, TIFFANY & CO. ring; and BULGARI cuff single earring. Studs, Taylor’s own.

This story originally appeared in the Winter 2023/2024 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.

See the story in our digital edition