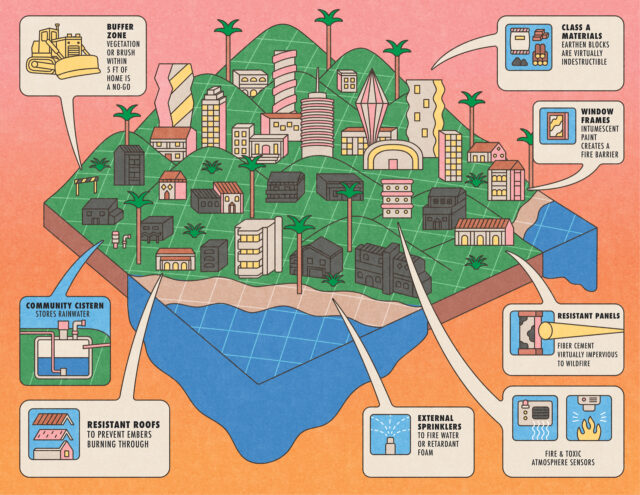

C Magazine quizzed the experts on the methods and materials to optimize for protection

Words by DEGEN PENER

Illustrations by SOÑA LEE

When fires rampaged through parts of Los Angeles in January, a few houses survived the lethal combination of 100 mph winds, flying embers, and brush that hadn’t seen rain in eight months. One in particular that stood strong went viral on social media. Designed by architect Greg Chasen for a client in Pacific Palisades, the house was a symbol of resilience amid the ash and rubble. It also became a template for fire-safe building practices: Chasen had incorporated walls made of fire-rated materials, tempered glass windows, a metal roof, and no vents into the home’s design. As L.A. residents, architects, and planners look to rebuild, many have taken note.

As L.A. reels from the devastation of the Eaton and Palisades fires, many residents who have lost their homes are eager to rebuild. With some 12,000 residences destroyed by the flames, the process will be difficult and costly (the L.A. Times says it could be up to $250 million), not to mention time-consuming — Blackrock CEO Larry Fink has said it could take a decade. Even after toxic substances are cleared the from scarred lots, rebuilding could be hindered by the high cost of building materials, the torment of dealing with insurance company hurdles, and building regulations. Some of those regulations — including requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act and the California Coastal Act — have been suspended by Governor Gavin Newsom. But the process is still daunting.

Those who lost their homes will also face several hard choices over how to rebuild. They are already trying to balance their desire to re-create their homes while making them more firesafe, especially from the ember-driven conflagrations that engulfed L.A. beginning on January 7.

“A big wave of homeowners want to rebuild what they had. They want their house back just like it was,” says Ben Kahle, a real estate agent with Historic Real Estate LA and a commissioner on the Historic Landmark and Records Commission for unincorporated L.A. County. “Rebuilding is such a feat. People are staring at this mountain, and they don’t know how to climb it quite yet.”

To help with that arduous undertaking, a number of L.A. architects and building experts shared with C Magazine their advice on constructing a firesafe home (known as home hardening) or simply improving an existing house. But there’s one big caveat: There are no guarantees. “Having worked on a few different rebuild efforts after [other] fires, the thing that you realize is that even best practices — such as using stucco, which is noncombustible — sometimes can’t help,” says Brian Wickersham of Aux Architecture. “Especially with fires like Eaton and Palisades that burned so hot and so intensely with the winds that we had.”

These architects also hope that Los Angeles will find a way forward that preserves the distinctive character of these communities. “I hope that there is not this knee-jerk reaction to say, ‘We’ve got to build these concrete homes,’ ” says Ben Stapleton, the executive director of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) California. “There’s a whole palette of materials you can select from that can be more fire resistant, feed into a beautiful design, and also have a lower carbon footprint.”

On the night that fire broke out in Pacific Palisades, embers were flying at architect Michael Kovac’s modernist home in the neighborhood. “It looked like a blizzard at Mammoth, except in embers,” says Kovac, who recorded footage using his home’s security cameras after he and his wife evacuated.

Their home survived, but “the houses just on either end of our house, 15 feet away, burned to the ground,” he says. Kovac credits the home’s array of fire-resistant materials (used when it was built in 2010), starting with covering the mostly wood-and-steel-framed house in fiber cement panel siding. “It’s virtually impervious to wildfire. It’s an incredibly dense cement material. You could take a blowtorch to it, and it just wouldn’t really care, which is basically what did happen.”

“One of the most effective things is if each house has its own water source and external sprinkler system.”

Other fire-resistant finishing materials recommended by design pros include traditional stucco, U-Stucco (made from cement and granular minerals specifically formulated to withstand heat and fire), Hardie board (made of cellulose fibers, sand, and cement), and even wood siding that’s permeated with fire-retardant chemicals. Some of these, like stucco and Hardie board, are relatively “inexpensive building materials, so you can minimize flame spread in a cost-effective way,” Wickersham says. He also recommends investigating whether a home’s concrete foundation can be retained. “There’s a process to clean the concrete, and then there’s a process to X-ray the rebar in the concrete to make sure it wasn’t damaged by the heat of fire. If we can preserve and build off the existing foundation, you’re a lot closer to your ability to rebuild. [A foundation] is 30 or 40 percent of the cost of a building these days.”

Homeowners looking to rebuild may also want to explore constructing a home out of virtually indestructible earthen blocks, an ancient building practice, or prefab options from companies like Kern County–based Plant Prefab and Turkel Design in Massachusetts.

One of the most vulnerable parts of a home is the roof. It should always be made of a Class A fire-rated material, which can include clay tile, metal, fiberglass asphalt shingles, and concrete tile. At the Getty Villa, which survived the Palisades fire, the roofs are covered in crushed rock. Kovac chose a synthetic thermoplastic polyolefin roofing material for his house in the Palisades. “It’s designed expressly for embers to land on it and not burn through,” he says. He also recommends installing a second fire-resistant layer beneath any roof covering. “We used DensDeck, which is a gypsum-based product that adds further fire rating.” A slanted roof can also be more fire-resistant than a flat one.

“Having more of a slope means that when embers come, they fall off the roof rather than sit on the roof. They fall down,” says architect Lara Hoad, who notes that flat roofs are an important element of midcentury design’s vernacular. “A sloped roof is a little bit of an antithesis to how we do things in California.” Overall, a fire-resistant roof should be designed to remove places where embers can gather and smolder, which is why some architects avoid using skylights in fire-prone regions. Similarly, overhangs such as eaves can be covered in soffit panels. “Ideally, you are creating smooth surfaces so that embers blow over the homes,” Stapleton says. (USGBC California has published a Wildfire Defense Kit for California Homeowners at usgbc-ca.org.)

“Vinyl windows just melt,” says David Hertz, an architect known for his sustainably built residences. And wood windows are easily combustible. Instead, the best bets are aluminum windows, preferably with tempered triple-pane glass. If a client has existing wood windows or prefers installing a wood window for aesthetic reasons, Kovac recommends coating the exposed surfaces in intumescent paint, which swells when exposed to high heat, ideally creating a fire barrier. In a worst-case scenario, where fire is approaching, a homeowner can also spray down wooden window and door frames with a gel-based, fire-retardant product called Barricade before evacuating.

Any fire-resistant home should also have vent covers that are designed to prevent embers from entering the home. “If you can keep the flames from getting inside, that’s the biggest thing that will help protect the building. Once the flames get in through the vents, that’s where we’ve actually seen buildings that burned from the inside out in a number of cases,” Wickersham says. Covering vents with 1/8-inch or 1/16-inch wire mesh or spraying vents with intumescent paint (“It’s super, super cheap,” Kovac says) can also help block embers. In the Palisades, Kovac gathered plumbing and exhaust vents in one location and then screened over them.

Adding protected vents, installing triple-pane windows, and covering eaves help protect against wildfire, but they’re also good green-building practices, Stapleton says: “When you’re leaking air, you’re losing energy.” Combined measures like these hew to passive home design, principles Chasen employed when building his home.

In fire-prone areas, it’s best to avoid planting vegetation within five feet of a home. This creates what’s known as a defensible space, defined by fire agencies as a buffer zone. If a homeowner wants to avoid a bare-looking perimeter, however, it’s best to choose plants that have high water content, like succulents or agapanthus. Native oak trees at the far edge of a property can also serve as fire breaks. “Oaks are well adapted to fire. When planted as a kind of grove, they end up creating an ember catch and a windbreak with their small leaves,” Hertz says, adding that “decks around a house are a huge problem. You’re bringing fire from the landscape right up to the building. The same with wooden fences. They are like wicks that just bring the fire right to the house. And Astroturf is flammable and horribly toxic.”

Homeowners should also be conscientious about clearing out dead brush regularly and should avoid garden designs that create a ladder for fires to move from a shrub to a tree and onto a house, according to guidelines from the state Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Sprinklers are required inside newly built homes in California, but many owners are considering installing private fire hydrants (connected to a pool or a water tank instead of the municipal water system; they start at $3,000 for equipment and installation but can run much higher) as well as sprinklers on top of a building. “One of the most effective things that could be done is if each house has its own water source and then to have an external sprinkler system that’s activated only the moment it’s needed,” says Hertz, who has a client whose home, equipped with a rooftop sprinkler system, survived the Palisades fire. “I’d much rather have sprinklers outside than inside.”

Extremely vigilant homeowners can also install systems that spray properties with fire-retardant foam. “We always knew that the biggest source of danger for us was a fire coming up the hill because it likes to climb up,” Kovac says. “So on our chimney, we had two commercial sprinklers that sprayed Phos-Chek, which is the fire retardant you see come out of the tankers, that orange stuff.” (Because power will often be out during a fire, any electricity-reliant fire-proofing measures would need to be powered by a generator.)

It’s important to remember, however, that the majority of the toxins in the ash and debris on charred sites came from inside people’s homes. The rebuilding process offers an opportunity to choose furnishings and interior materials that are better for the environment and its occupants. “We cannot build with these toxic materials anymore … because we’ve seen the end life of these buildings,” says Hoad, a professor at Otis College of Art and Design. A great resource for exploring options — like low VOC paints, insulation made from natural materials, and bio-based flooring — is the Parsons School of Design’s Healthy Materials Lab (healthymaterialslab.org). Interiors also burn faster today because of the presence of plastics and other synthetics. A recent study by Underwriters Laboratories found that the interiors of homes dominated by furnishings made with synthetic foams and fabrics can be engulfed by flames in less than four minutes.

Although some families, especially in the wealthier Palisades, will be able to afford many fire-proof innovations, other homeowners won’t be so lucky. “We’re talking to families in both areas [the Palisades and Altadena], and almost all of them have the same issue: Their payout is going to be less than the cost for construction to rebuild,” Wickersham says. “Most of the payouts won’t make the people whole for the loss. And that’s a painful thing to hear.”

Amid rebuilding efforts, there’s also the persistent question of whether the fabric of neighborhoods can be preserved, whether in Altadena’s Black community or the Alphabet Streets in the Palisades. There are worries that developers will buy up lots and tract homes will replace midcentury and Craftsman homes with nondescript, high-density townhomes. It’s also likely that certain areas will become even more affluent, dominated by bigger and more luxurious multilot estates. Other fire-devastated communities in the West have seen this happen.

Community-centered planning offers another way forward. Hertz says one of his dreams is for cities to create more green space for residents that can also serve as firebreaks. “Planted with oak trees, these parklets would provide ecosystem services to residents,” he says. Hoad would like to see residents on a street come together to invest in underground community cisterns, which can store rainwater for emergency uses and for irrigation amid California’s droughts. In Altadena, the architecture firm Lovers Unite has already spoken with a client who wants to work with her neighbors “on a shared vision where they plan around each other’s needs and maybe they can get one contractor to work across the neighborhood,” cofounder Alan Koch says. After the Woolsey Fire, which burned 96,000 acres in L.A. and Ventura counties in 2018, Wickersham worked with a client on a cul-de-sac where neighbors pursued just such a strategy. “They hired a single general contractor and design team in order to try to get the economy of scale,” Wickersham says. “The idea being that if you hire one contractor, it’s one job site trailer, it’s only one dumpster.”

Interior designer Jaime Rummerfield, also the cofounder of the nonprofit Save Iconic Architecture, is working to jump-start a new Case Study program that would develop blueprints for distinctive California homes designed for the fire-prone era. “It would be an amazing opportunity to create 20 houses for the future of Los Angeles,” Hoad says. It may not be feasible to perfectly re-create an early 20th-century Craftsman cottage that was lost in the fires, but architects can work to retain elements of that aesthetic that will gratify homeowners still hurting from the loss of their beloved homes. Karen Spector of Lovers Unite says it sometimes comes down to simply retaining the scale of a lost home or creating an interior with built-in cupboards. “Some people come to the table thinking there’s a replica rebuild or a glass box and they can’t see anything in between,” she says. “But you don’t have to have a super-muscular architectonic home. You can build a new home that is lovely. And Altadena is unique because there are a lot of really small modest houses on big lots. I think if people now rush to kind of max out, it’s going to really change the feeling of the neighborhood.”

Ultimately, Kahle says, rebuilding is about more than materials. “If you don’t have the community within those structures, you also lose the neighborhood, you know? In Altadena, it’s so multigenerational. There’s a big African American community there. There are people who are passionate about the neighborhood. And that’s what you’ve got to keep. If you lose the people, you lose the soul.”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more DESIGN news.

See the story in our digital edition