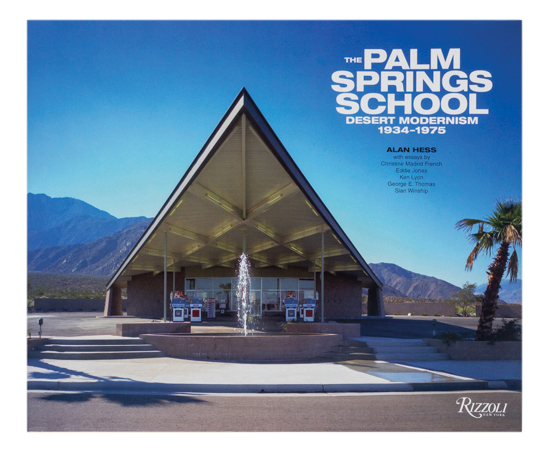

A new volume explores the influential group’s free-ranging impact on modernism

Words by ALAN HESS

Nature is an immediate presence, a genius loci in the Coachella Valley with its geological hot springs close to a major earthquake fault, strong winds blowing through the pass between Mount San Jacinto (10,834 feet) and Mount San Gorgonio (11,503 feet), canyon streams lined with native palm trees, the mountains’ brown and gray summer colors turning to carpets of green and yellow in winter, and a gentle wintertime climate occasionally accompanied by gully-washing monsoon rains. Over it all rises the dramatic rock wall of Mount San Jacinto, three blocks from the center of town. The sun disappears behind the western mountain early, while light reflecting off the low eastern hills lingers. The light from long sunsets changes every day and every season. Nature renders Palm Springs extraordinary.

Nature is both a blessing and a challenge. It might be said that technology dominates because it masters nature’s extremes. It could just as easily be said that nature itself is the dominant presence, and technology in all its avatars is only playing catch-up.

The desert imprinted itself in the work of each Palm Springs architect.

In the beginning, it was scalding primordial water heated deep within the earth’s crust that produced the soothing hot mineral spring that the Cahuilla people enclosed with simple wood huts, later replaced by the elegant concrete arcades and tiled pools of the Spa Bathhouse by William F. Cody, Wexler & Harrison, and Philip Koenig. The spring attracted vacationers and tourists to Palm Springs, thereby creating an enduring recreational economy. Nature, technology, and the local economy intertwined to form a distinctive philosophy in these notable buildings.

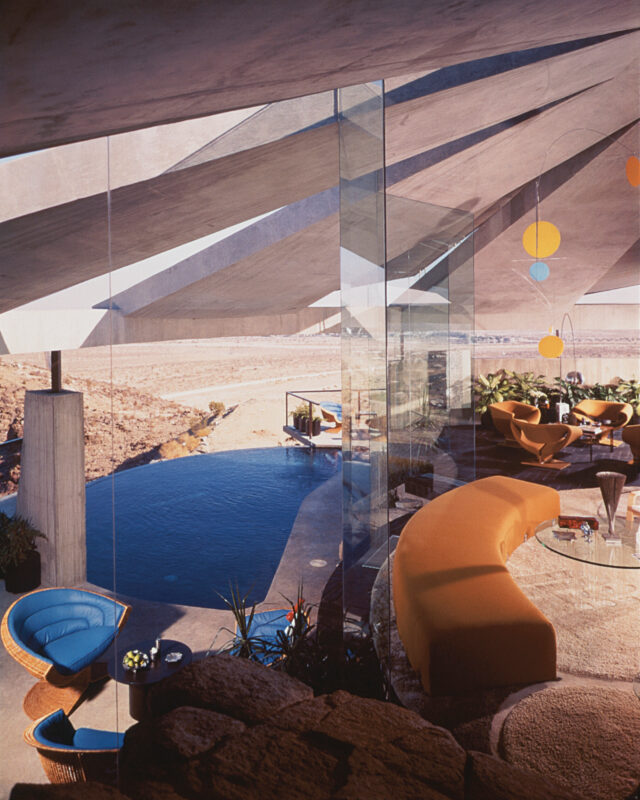

The desert imprinted itself in the work of each Palm Springs School architect. They did not so much bring Modern architecture to the desert as they brought the desert to Modern architecture. The abstract silhouettes of the mountain found their way into the oblique front wall of the Del Marcos Hotel (1947), Cody’s first building in Palm Springs. Rock added rugged texture to the cantilevered concrete wings of E. Stewart Williams’ Palm Springs Art Museum; to the battered walls of Lloyd Wright’s Institute of Mentalphysics topped with broad concrete trellises; to Armet & Davis’ Denny’s restaurant supporting a cantilevered boomerang roof; to the living room of John Lautner’s Elrod House designed around boulders exposed when the architect excavated the ridge line, then capped it with a spectacular concrete compression ring. At the tribe’s Spa Bathhouse, Wexler, Harrison, and Cody used random-sized natural cobble stones from the streams running off the mountain, held together with mortar, to cover walls in the hot springs treatment areas.

Visually, natural desert colors found their way into homes, patios, and walls. The dusty rose, sage green, and palo verde yellow colors that artist Millard Sheets used to paint Webster & Wilson’s Ship of the Desert (1937) and Albert Frey applied to the corrugated fiberglass panels at the Premier apartments (1957) were borrowed from springtime desert blooms.

The desert environment changed its architects over the course of their careers. After celebrating the Aluminaire House’s gray and silver metal in New York, Frey discovered the rainbow of soft natural colors in Palm Springs. He maintained his fascination with U.S. industrial mass production but would tint the manufactured composite panels at the Cree (1955) and Carey-Pirozzi (1956) houses a desert green. He embedded rose pigments integrally in the concrete blocks he used for houses, gas stations, and churches. He and partner Robson Chambers coated corrugated metal — a favorite material — with sky blue for the ceilings of homes. Frey translated yellows into vinyl fabric lining the pleated walls of Frey I’s bedroom.

The balance between nature, technology, and recreation’s presence varies from architect to architect. At the Kaufmann House, the silver and gray metal structure is almost purely technological — a steel- and-glass tent purposely set against the irregular backdrop of the mountain. On the other end of the scale, the organic shapes of surrounding rock formations almost entirely define the structure of the Doolittle House. Between these ends of the spectrum the dramatic cantilever roof of E. Stewart Williams’s Edris House is carefully balanced by the prominent rock-clad chimney that anchors it in the ground.

Feature image: Albert Frey House l a.k.a. Frey I with Albert Frey Seated, Albert Frey, 1940. PHOTO: Unknown.

This story originally appeared in the Men’s Spring 2025 edition of C Magazine.

Discover more DESIGN news.

See the story in our digital edition