How the daughter of the late, great California craftsman J.B. Blunk keeps her father’s legacy alive among the redwoods

Photography by ALANNA HALE

Words by CHRISTINE LENNON

J.B. Blunk’s youngest child and only daughter, Mariah Nielson, at home at Blunk House in Inverness.

Mariah Nielson spends her days in a coastal haven dotted with dense redwood groves, an oyster-rich bay, and wind-swept Pacific bluffs that blur her past and present. As the director of her late father J.B. Blunk’s estate in Inverness, she is the shepherd of his legacy as a multidisciplinary modern California artist known for a rustic, organic aesthetic working in wood and clay.

Nielson and her husband wake up every morning in her childhood home, the iconic Blunk House he built from salvaged wood and local river rocks, where even the bathroom sink is hand-carved from a single piece of redwood. Her 5-year-old son sleeps in the same loft she did as a child. At the office and gallery space in nearby Point Reyes, she plays “art detective,” fielding messages from eager collectors who believe they have one of Blunk’s famous phallic stools or chainsaw-carved sculptures. And she curates exhibits featuring the work of artists who feel connected to his playful aesthetic. Blunk and her mother, Christine, were known for hosting dinner parties with the tight-knit artist community in town, and Nielson is keeping that tradition alive, too.

“Forgive me for the noise in the kitchen,” she says by phone, with a clamor of pots in the background. “I’m making chicken tacos for the team that’s here installing our new exhibition with Adam Pogue and Martino Gamper. We’ve been having dinner together every night.”

Nielson understands that part of the job is reminiscing about her unique family history and chatting about her father’s vast body of work, which covers disciplines from wood sculpture to furniture to painting to ceramics to architecture. She began working as the estate director in 2007, then opened the Blunk Space gallery, attached to her office, in 2021. As a trained architect who studied at the California College of the Arts, a design historian with a master’s degree from London’s Royal College of the Arts, and an experienced curator, Nielson has a unique understanding of her father’s contribution to the mid-twentieth-century arts. But the story begins long before then, during afternoons she spent watching her father work.

“His work transcends art, craft, and design”

Mariah nielson

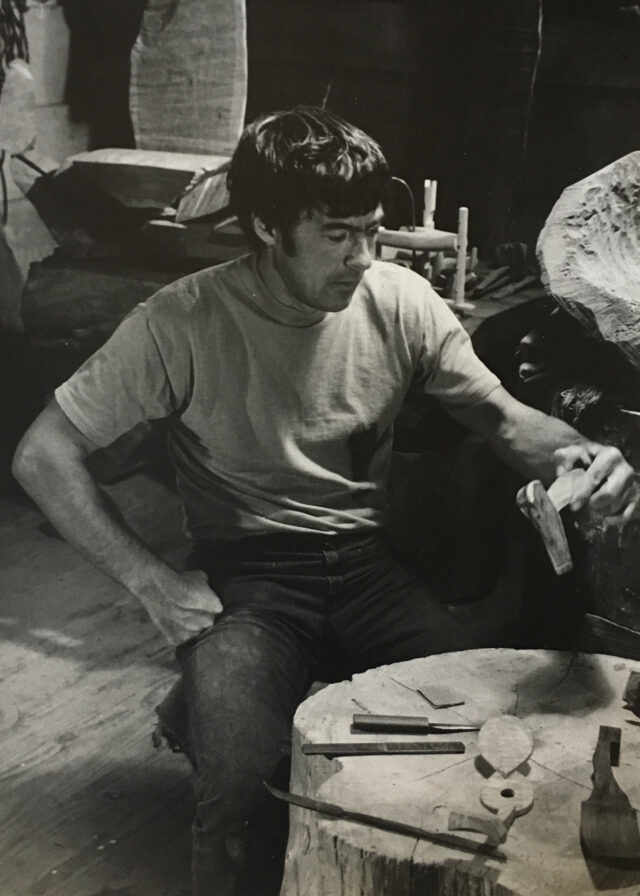

J.B. Blunk working in his Inverness studio, 1968.

“I would make the 30-minute walk up the steep hill to our house on the ridge after school every day,” she says. “My mom was running Coyuchi, the organic bedding company in town. So I’d walk home, and if I wanted to spend time with my father I’d have to come up with my own projects in the studio. He didn’t mind me being there with him, but I had to stay busy. He’d work until about 6, and we’d all have dinner as a family. He was always working, seven days a week. He was also a very social person and he loved having dinner parties. It just had to be on his time.”

Blunk and his contemporaries helped establish the sleepy, misty small town in far west Marin County as a contemporary art destination. But his path to rural California was as twisty and unconventional as his sculpture: He grew up in a conservative Kansas family and came west to study physics at UCLA. “After a year in the program they asked him to take an aptitude test, which I assume meant he was not doing very well,” she says. “That’s when they transferred my father to the ceramics department, which was a major shift in his life.”

The influential artist Laura Andreson, who founded the ceramics department at UCLA in the 1930s, was his teacher, and she took his class to a Mingei pottery exhibit at Scripps College. “He saw Shōji Hamada’s work and just knew in that moment that he wanted to be an artist,” Nielson says. “He made it his intention to meet Hamada and apprentice with him.”

When he was drafted into the army during the Korean war, Blunk saw it as an opportunity to get closer to his idols in Asia. After he was discharged, he went straight to Tokyo, where a chance meeting with modernist Isamu Noguchi while they were both admiring the same piece of ceramics in a Mingei store cemented Blunk’s future. The two became friends, and Noguchi arranged for two apprenticeships for Blunk in Japan. Back in the States, he taught ceramics, married his first wife, Nancy, and moved to San Francisco, where he worked odd jobs, sometimes doing carpentry work. Surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford hired Blunk to construct the curved roof of his home in Inverness, and then gifted Blunk a one-acre plot on his land to build his own home and studio.

Nielson lounging on a Martino Gamper & Adam Pogue collaborative piece in the gallery.

For decades until his death at 76 in 2002, Blunk was a prolific artist. He made rugged, organic sculptures from found old-growth redwood stumps and discarded wood pieces from the local logging companies and sawmills, carving them into cubist shapes with a chainsaw or sanding them into smooth, undulating curves. Blunk’s most recognizable work may be his phallic three-legged stools, although people more familiar with the estate may argue that the house itself, which was initially just a 600-square-foot structure, has become his most iconic work.

It took some years, however, for his only daughter to understand the singularity of her father’s masterpiece, that it was not simply an odd house with a little loft nook for her to sleep in. “To be born into a place like this meant it was all I knew. It was normal,” she says. “It was and still is the most specific place. Then in middle school I started to understand the work my father was doing. By the time I left home at 16 to work as a model in Japan, I spent time learning about the time he spent there and the influence it had on his life.”

“My older half-brothers always joke that I got the better version of our father,” she says, referring to the children Blunk had with his first wife. “He was 52 when I was born, so he was older and had some perspective. He was more established. He had collectors and connections, when before he had struggled to make ends meet financially.”

“I get emails saying ‘ I have a Blunk.’ And I know it’s not”

Mariah nielson

The home and office, including this brutalist desk, remain largely untouched since the artist’s death.

Today, as an art historian and curator, Nielson explains that her father’s work defies categorization. She describes his style as very honest, playful, and intuitive. He had a profound connection with nature, and there are layers of meaning, spirit, and intention in every piece. “It transcends the traditional categories of art, craft, and design,” she says. “Everything he made slipped between those categories.”

Mariah Nielson has become so attuned to her father’s work that she can tell almost instantly if work is his, even if his signature chiseled initials are missing. “He didn’t keep records about what he made and who he sold it to, and he rarely signed his work,” she says. “When he did, there were well-known signatures that developed over the years. He would spell his entire name out using a nailhead, or he would carve his signature J and B connected with a chisel. I get a lot of emails from people with shellacked wood sculptures saying ‘I think I have a Blunk.’ And I know immediately that it’s not.”

When she isn’t playing art investigator (note to hopeful collectors: Blunk wasn’t a fan of shellac), Nielson coordinates exhibits for Blunk Space, which brings us back to that taco dinner-in-progress. Nielson is days away from opening a new exhibit with original work by Los Angeles–based textile artist Adam Pogue, who makes piece-work quilts, pillows, and tapestries on commission and in collaboration with Commune Design, and London-based Martino Gamper, who is best known for his “100 Chairs in 100 Days” project, for which he re-imagined scavenged and salvaged chairs into one-of-a-kind works of art. Both artists are deeply familiar with Blunk’s work, and Nielson invited them to spend time at the Inverness studio.

“Adam spent about ten days here over the summer, and Martino has been here at least ten times over the years,” she says. “We don’t call it a residency. We consider it a part of the gallery programming. The place has an impact on the work. I think there are so many lessons to extract from this place in terms of sustainability, and the cross-discipline nature of JB’s work.”

Mariah Nielson is enjoying the resurgence of interest in her father’s work, which is driven primarily by the interior design community that has embraced his rough-hewn, organic aesthetic — although she is very aware of fleeting tastes. “I wonder how long it will last,” she says. “His style of work fell out of favor in the ‘80s, and I expect that this kind of work will not be of so much interest in ten years. Then it may come back again.” For the moment, she is enjoying watching her son explore the nooks of the house she loved as a child, and the wonder of the surrounding woods. Blunk died in the house, and his presence is very much alive within it.

An Adam Pogue cushion in the center of a room that embodies the Blunk spirit: organic shapes, warm colors, rustic simplicity, and sculptural wood pieces that blur the line between art and craft.

Rough plank walls and a hand-hewn bed, Blunk’s take on Japanese minimalism, are at home in west Marin County.

Nielson at home in the small but functional kitchen.

Nielson’s parents decorated the cozy living room, part of the original 600-sq.-ft. cabin, with finds from their travels.

TAYLOR HILLS wears GIVENCHY jacket, shirt, and jeans; BUCCELLATI bracelet, TIFFANY & CO. ring; and BULGARI cuff single earring. Studs, Taylor’s own.

Feature image: Nielson at rest in Blunk House.

Portions of this story originally appeared in the Fashionable Living and Winter 2023/2024 issues of C Magazine.

Discover more DESIGN news.