…as 35 years of his activist art come together for a new exhibition in an election year

Words by STEPHANIE RAFANELLI

All images courtesy of the artist / ObeyGiant.com.

Fairey’s work takes inspiration from Soviet-era agitprop.

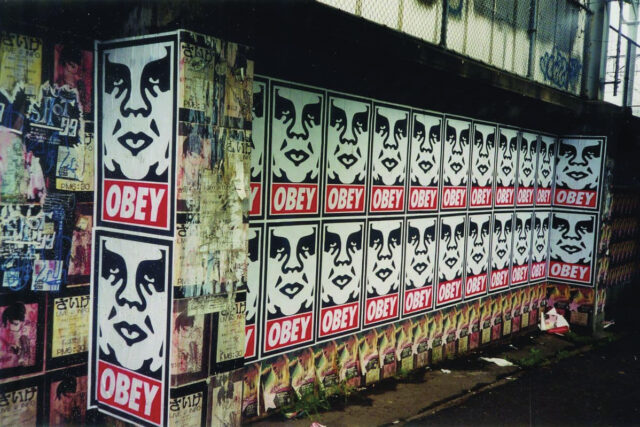

Fifty-something New York street artist Kaves once daubed: “Graffiti writers never die. They just fade away.” Like Kaves, L.A.-based contemporary Shepard Fairey, 54, has done no such thing. After 35 years of activism, in which he has played David to the sociopolitical Goliath through graffiti, screen prints, artworks, and street murals — all evolved from his notorious viral sticker campaign “André the Giant Has a Posse,” which questioned governmental control of public space in the late 1980s — Fairey has shown no sign of letting up or diluting his art’s progressive messages. He declares he has been “manufacturing quality dissent since 1989” on his website Obey Giant, which bares both his manifesto and his prolific output of art (often available as posters for free download or with profits donated to charities) on pertinent themes of societal, racial, political, and environmental justice.

Stylistically borrowing from Soviet-era agitprop, Fairey attempts to appeal — in stark contrast to conventional politics — to some highest common denominator in all Americans by playing the idealizing iconographer of symbolic heroes. His “We the People” series of Latino, Muslim, Native, and Black Americans as emblematic U.S. citizens were famously held aloft as antidotes to discrimination at U.S. Women’s Marches in 2017. Fairey is unequivocal about the democratic power of public art and activism. “People call the internet the digital town square. It’s more like the public toilet,” he says via Zoom from one of his two L.A. studios (he has one space for fine art in Frogtown and another for design in Echo Park).

His most renowned work is the “Obama Hope” poster, of which 300,000 copies and 500,000 stickers were distributed in 2008 in a feat of grassroots electioneering. The New Yorker called the poster “the most efficacious American political illustration since ‘Uncle Sam Wants You,’” and it now hangs at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Fairey has been described as an heir to Keith Haring, whose work also went from the streets to galleries to museums, as well as a successor to the legacies of Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp’s conceptual art. His activist clothing label was once dubbed “the anti-corporate, anti-Man street unbrand.”

But his brand of populism has its haters, and some people think he has sold out with his giant publicly sanctioned murals, which are partly painted by assistants. Fairey has completed more than 135 murals around the world, including a nine-story-high Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg (2014) and Marianne of France in Paris’ 13th arrondissement after the 2015 attacks. Around 10 murals have become part of the fabric of L.A., from Hollywood Library’s “Peace Elephant” (2011) to “Maya Angelou Rise Above” (2019) on East 53rd Street.

“I feel disappointed and disillusioned, but not paralyzed or demotivated”

shepard fairey

Guns and Roses, 2006.

“I still do street art without permission,” Fairey says. He has been charged at least 18 times for vandalism-related crimes. “Street art has that transgressive quality when it’s done as a hit-and-run thing,” he notes. “It’s visceral. But a mural has a visceral quality, too, because it’s literally changing the urban landscape and it’s not done by the government or a massive corporation. What people don’t understand is that my approach was never ‘I’m only going to do things illegally because I’m anti-establishment and that’s the single way I define myself.’ I think that’s really selfish and obnoxious. But I’ve evolved away from just saying, ‘The status quo structures need a little wrench in their spokes’ to looking to make a difference by working with organizations and recognizing the value that the fabric of society provides everyone. Because society is a [Gaia-like] organism where all the parts are intertwined. [People] not respecting that and [acting only in their own self-interest] creates a lot of our problems. It makes even the lives of the middle class worse. Because only the top one percent can get away with being selfish jerks and souring it for everyone else.”

He’s now a big promoter of civic participation. “Everyone is a selective libertarian these days. They take for granted that their trash is taken out, they have a paved road and electricity; all the things that are generated by society and government for the collective need that make their vision of themselves as a ‘supremely brilliant independent being’ possible.”

Alongside his turbo-charged “Obama Hope” campaign, Fairey has been involved with 15 voting drives over his career. “I’m very involved with the Get Out the Vote drive working both directly with people in government [like U.S. Representative for California Adam Schiff] and a bunch of organizations,” he says. He has his work cut out for him this year. It doesn’t help that there’s an Obama-shaped hole in an uninspiring political lineup for the 2024 presidential election. “Obama was a once-in-a-lifetime candidate for me. I’ve never known anybody as compelling. I think that sets expectations really high for people,” he says. “I do think Joe Biden is a very decent human being who has evolved to become more progressive. He doesn’t have the skills as an orator or the same charm. That’s unfortunate.” Fairey’s number-one priority, he says, is “making people consider that if things are imperfect, they are more imperfect when there isn’t robust civic participation, which doesn’t mean just voting. It means being aware of issues that shape [our] culture and using your voice.”

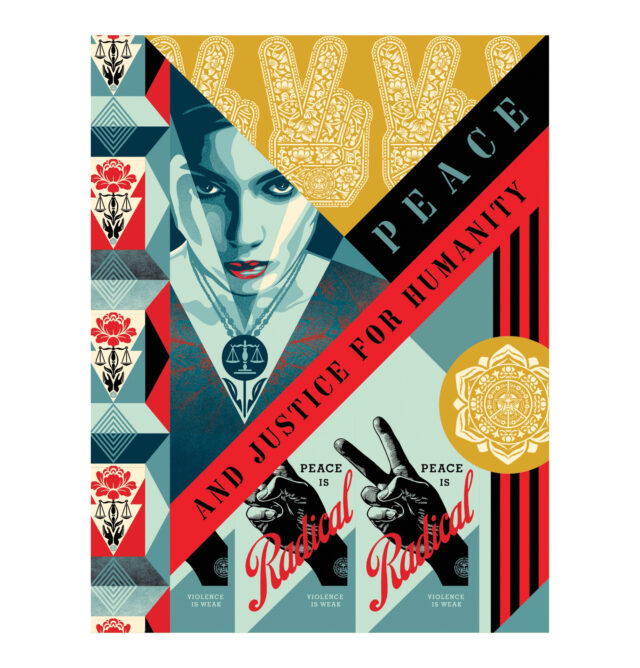

Fairey’s show Peace Is Radical opened in January at the ReflectSpace Gallery at Glendale Central Library.

But how does he combat feeling weary about the Groundhog Day–like cycle of American politics? Fairey says that there’s a lot to be disenchanted with on both sides of the political fence. On the left, he says, it’s philosophical hairsplitting “and the apathy and malaise. It’s so counterproductive and a waste of time, and it ends up demotivating people who are on the same side. And [on the right] the fearful and hateful side of people has been stoked so effectively. I feel very disappointed and disillusioned. But I don’t feel paralyzed or demotivated.” Frustration seems to be his fuel. “My parents learned quickly that the more they tried to dissuade me from something, the more motivated I became,” he says. “I do like a challenge. But I don’t like the weight of the challenges we are dealing with [in this election]. It’s really heavy.”

It’s easy to imagine the election as the dominant topic of conversation in the Fairey household this year. Based in Los Feliz, Shepard and his wife of 22 years, Amanda, have two teenage daughters, Vivienne, 18, and Madeleine, 16. So how does his family feel about his indefatigable idealism and social commitment? “My kids sometimes say that I’m too obsessed, that I don’t give people in the family as much attention. Or when they are being really mean, they will say that I’m doing these things because I’m a narcissist and I want to be given credit for being a do-gooder. And that’s not true.” He hesitates. “Of course, for all the mudslinging that goes on, it’s very nice to be recognized for at least trying.”

“The status quo structures need a little wrench in their spokes”

shepard fairey

Born to Strait Fairey, a doctor, and Charlotte, a real estate agent, the pertinacious young Shepard developed his fierce sense of social justice in the 1970s while growing up in Charleston, South Carolina. “Charleston was almost exactly half Black and half white, and with a few exceptions the top 50 percent economically were white and the bottom 50 percent were Black. It seemed really uncool to me. I asked a lot of questions about social structure. My school was also a microcosm of what was wrong with society: If you wore expensive preppy clothes, you came from money, and you were a good athlete, you were OK. Everyone else was to be bullied.” He soon honed a defiant streak. “I was very insecure as a kid, but I started listening to the Clash and the Dead Kennedys, who had some really thoughtful lyrics about conforming, U.S. foreign policy, and fascist tendencies. Later I got into Public Enemy. I started seeing people making art that I thought was visceral and a very powerful articulation of ideas, and I thought, I want to do stuff like that.”

Teenage Fairey showed a talent for disruptive, conceptual ideas. While studying at Rhode Island School of Design, he prefigured the internet meme with his ambiguous sticker of French wrestler André René Roussimoff (André the Giant), a victim of gigantism at 7 feet 4 inches tall and 520 lbs. The East Coast skater community distributed the sticker by hand in 1989, with tens of thousands mysteriously popping up around the world by the ‘90s. The Village Voice called Helen Stickler’s 1995 documentary about André the Giant “a canonical study of Gen-X media manipulation” and “one of the keenest examinations of ‘90s underground culture.” Fairey says, “I could never replicate the campaign now. Part of the power of the André sticker was the mystery around it. Now someone would just look online and whoever thinks they are clever on Reddit would explain it away.”

After graduating, Fairey moved to California — first to San Diego and then Los Angeles in the early 2000s, where he cofounded commercial design agencies, masterminded guerrilla marketing campaigns, and created album artwork for Led Zeppelin’s Mothership and Smashing Pumpkins’ Zeitgeist. Things didn’t “coalesce” for him as a contemporary artist, he says, until after he saw the photo-and-text collages of Barbara Kruger and the work of L.A.-based guerrilla street artist and political satirist Robbie Conal, with whom he would collaborate in 2004 as art collective Post Gen (along with fellow L.A. street artist Mear One) for “Be the Revolution,” an anti-Bush, anti-Iraq war street art campaign. Conal’s work also inspired Fairey’s “Obama Hope” poster, which was originally emblazoned with the word progress — Team Obama asked him to change it to hope. The artist was named as one of GQ’s Men of the Year in 2008 for this work, but he was also charged with criminal contempt in 2012 for “destroying documents and manufacturing evidence” that covered up his breach of copyright by using an uncredited image by photographer Mannie Garcia. He did get a thank-you letter from President Obama, however, and the Fairey family was invited to the White House the day after Donald Trump was elected in 2016. “I thought he’d cancel because that election result was so unexpected, but he spent about 40 minutes with us,” Fairey says. His poster of Nelson Mandela hangs in Obama’s Chicago office.

“Obama was a once-in-a-lifetime candidate”

shepard fairey

Fairey’s art hangs in places as lofty as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A., and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He had six global exhibitions last year, including one at Singapore’s Opera Gallery — he also painted the “Mosaic of Peace & Harmony” mural in the city’s Chinatown — and Shepard Fairey: Icons at L.A.’s Subliminal Projects. Peace Is Radical subsequently opened in January at the ReflectSpace at Glendale Library, Arts and Culture. The timing couldn’t be more tragically on point for a thematic curation of his works against oppression and violence. “I made the “Peace Is Radical” poster 18 months ago, so it was after the war in Ukraine had started but before what’s happening in the Middle East.” He says he’d like to do a street mural in Gaza: “I’ve even reached out to see if it could happen. I’d be interested in doing a mural in Ukraine as well. But it’s very tricky. Some people see art as an essential tool for promoting and reinforcing humanity [even in inhumane circumstances]. But other people consider art to be a frivolity while human beings are being killed.”

On show are Fairey’s screen-printed portraits of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Ai Weiwei, as well as a lithograph of “Obama Hope” and graphic collages of symbolic figures with peace signs, doves, scales of justice, and lotus flowers. “I used to say to myself, I’m never going to use a flower in anything I do. I’m never going to use a seascape. Because those things are clichés. But then I realized they are cliché because they connect emotionally for people. [That’s why] they are on greeting cards — they are universal symbols.” There also seem to be references to multicultural religious iconography in his more recent work. “Religion was the most pervasive language and culture for centuries,” he says. “[And my work] isn’t meant to be opaque at all; it’s meant to be very clear. The idea of how you were supposed to live your life morally was connected to religious allegories and their symbols. My work is secular, but it also may be spiritual in appealing to a higher purpose than ‘I define myself by how many likes I got on Instagram and by what clothes I wear.’”

Fortunately, his teenage daughters are too evolved to do that. “The girls were on Instagram for a while. Now they don’t really post or participate. They learned, both around age 14 or 15, that it was a source of perpetual anxiety and perpetual maintenance. It’s a time suck. They decided that they could just step off that treadmill.” They can even out-woke their dad. “Yesterday I used the word exotic and they told me off and said it’s like saying ‘Oriental,’” he says.

But Fairey is no stranger to jibes. “I wish I were thicker skinned because it always hurts, but I would feel worse if I became apathetic out of fear of a negative response. But we live in a world now where everybody’s got a megaphone. So I just do what I believe in and hope that when the dust settles on things, time will back my approach.”

AMANDLA STENBERG wearing BOTTEGA VENETA.

Feature image: Artist Shepard Fairey working on portraiture for Shepard Fairey: Icons at L.A.’s Subliminal Projects.

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more DESIGN news.

See the story in our digital edition