A closer look at the form-follows-function aesthetic of Scott Mitchell’s SoCal houses

Words by PAUL GOLDBERGER

It would be futile to ask whether Scott Mitchell is a modernist or a traditionalist; indeed, you could say that one of the essential points of his work is to blur that distinction, which is generally beloved by critics and theorists and matters little to anyone else. Mitchell brings elements of traditional architecture into modernism, and he brings elements of modernism into traditional architecture. He knows that space and light and proportion and texture mean much more than style, and he knows that architecture is an art of composition in three dimensions, and that the aesthetics of composition are only a part of what makes a work of architecture succeed. There is always texture in a Mitchell house. Nothing is flat, and nothing feels too sleek or shiny.

Mitchell, it is clear, is no theorist. He is not interested in designing buildings that exist first to promote an intellectual position, and second to respond to a functional need. He is more inclined to start with the functional need and then see how broad and rich an experience he can manage to create in the course of fulfilling it. You see that, surely, in the Holmby Hills house in Los Angeles, one of the grandest villas that Mitchell has yet produced, where he gracefully melds together elements of sources as diverse as the beaux-arts, Frank Lloyd Wright and 20th-century industrial modernism, and makes of it all something whole, elegant and comfortable.

No one could call any of these projects modest, and none of them is small. But the more you look at them, the more you realize how well they have been edited, so to speak, how little excess there is in them, despite how large and ambitious they are. Mitchell’s two houses in Malibu make the point well: one is a long structure of concrete and glass, low slung before the sea, a pavilion expanded to monumental scale. The other, Paradise Cove, is higher and more varied in its form, with some peaked-roof interiors, a slightly more domestic air, and a more oblique relationship to the ocean. They are different in multiple ways, and neither, of course, is a simple house, or a plain one by any measure. But they share the quality of having nothing unnecessary about them, no useless lines, no extra spaces, no materials or colors that have been put there just for their own sake. Everything is part of the whole, and the whole design is an object of richness and restraint, in equal measure.

In the affluent Holmby Hills district of Los Angeles, a newly commissioned house feels like a modernist reinterpretation of a Palladian villa in the articulation of its facades and hierarchy of interior spaces. A great room 31 feet high has pivoting glass doors and a bridge that separates the master suite from the guest bedrooms. Six panels of dark oak were hand-adzed by esteemed furniture maker and friend Joel Brown to form the balustrade. Wide floorboards are center-cut old-growth oak from southern Germany, with matched grains. Bronze door handles and faucet levers were inspired by a golf putter that Mitchell found at a flea market and are now produced by Sun Valley Bronze. Mitchell also designed the drought-resistant landscaping and an infinity pool lined in dark granite that mirrors the trees.

An ambitious remodel of a former horse farm is located near Paradise Cove, a few miles up the coast from the Malibu House. Here, Mitchell returns to his first love of country barns, but the reconstruction of the old buildings has a new rigor. The main house sits on a bluff and is hinged in plan to offer two perspectives of ocean and shoreline. The great room projects out at one end and pocketing glass sliders on three sides transform it into an airy portico. The interior of the house has white oak tongue-and-groove paneling and a layered ceiling of joists and purlins. Mitchell master-planned the estate, creating outdoor rooms to complement the two guest houses, screening room and nine other subsidiary structures.

Excerpted from Paul Goldberger’s foreword from Scott Mitchell Houses (Rizzoli New York, $65) by Scott Mitchell.

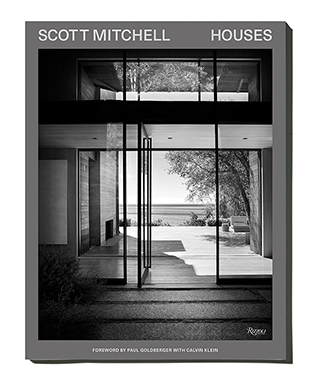

Feature image: Architectural designer SCOTT MITCHELL. Photo by Steve Shaw.

May 14, 2020

Discover more DESIGN news.