The feminist artist with a taste for pyrotechnics opens up about her biggest year yet

Words by MATT STROMBERG

Despite her name, Judy Chicago is inextricably linked to the West Coast. “I’ve always maintained that my artistic roots are in Southern California, as I developed as an artist there in the 1960s and ’70s when the spirit of self-invention was strong,” she says from her home in New Mexico, where she’s lived for the past 34 years.

And the pioneering feminist artist, now 80 years old, is coming back to California. This May, San Francisco’s de Young museum will unveil an exhibition that reflects her five-decade career. And although Chicago has long been a vital force in contemporary art, this marks her first comprehensive retrospective. That it should open in California is significant, as it was here where Chicago spent her formative artistic years.

“Art has no responsibilities. Only artists have responsibilities”

Judy Chicago

She received her Master of Fine Arts at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1964; founded feminist art programs at California State University, Fresno, and the California Institute of the Arts in the early ’70s; and debuted her most famous artwork, The Dinner Party, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979. A massive, five-year undertaking produced with scores of collaborators, The Dinner Party is composed of 39 place settings for historically significant women — including Sacagawea, Sojourner Truth, Virginia Woolf and Artemisia Gentileschi — at a triangular table. Chicago enlisted artisans who specialized in crafts that were often dismissed as decorative or “domestic art,” such as ceramics and embroidery, to create the labor-intensive place settings, many of which feature plates decorated with stylized, sculptural vulvas.

“San Francisco plays an important role in the history of the reception of the work,” explains exhibition curator Claudia Schmuckli. “It was displayed to enormous popularity and was a highly attended exhibition that drew thousands of visitors, but it was critically annihilated by the art establishment. An institutional tour was never realized. Judy went ahead with volunteers to make a world tour of The Dinner Party. It was an entirely grassroots effort.”

Despite its initially harsh critical reception, The Dinner Party is now regarded as one of the most influential works of feminist art. Since 2007, it has been permanently housed at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

With the retrospective, Schmuckli aims to introduce audiences to Chicago’s rich oeuvre beyond her most well-known work. “Many people primarily associate her with The Dinner Party because it was so important and notorious,” Schmuckli says. “They don’t know the full scope of her practice. The goal is to paint a broader and more nuanced picture of who she is as an artist.”

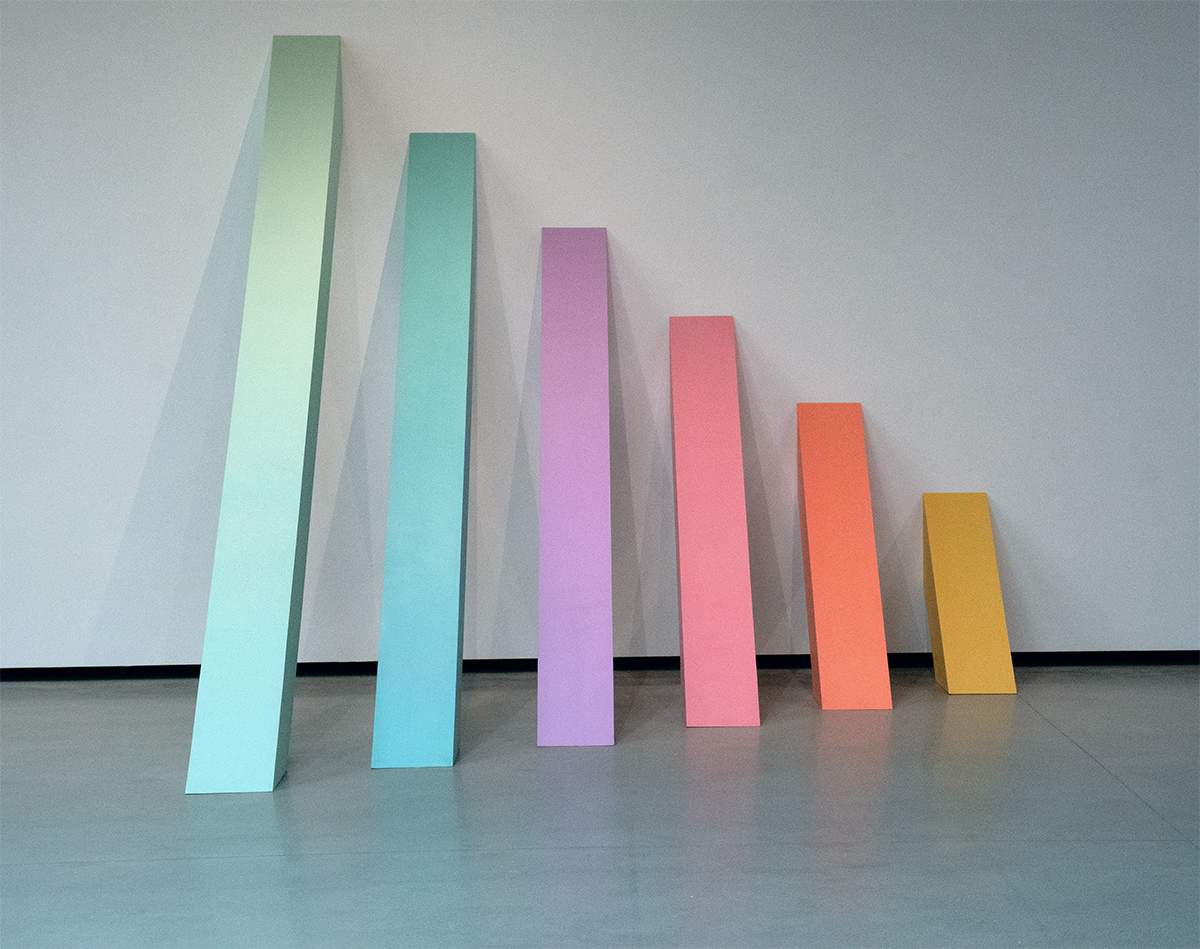

To this end, the retrospective will feature 150 pieces, ranging from her early forays into minimalism and the California Light and Space movement to iconic milestones in the history of feminist art, such as “Birth Project” (1980-1985), a response to the lack of birth imagery in art; “PowerPlay” (1982-1987), a series of paintings, weavings and bronzes exploring the construct of masculinity; “Holocaust Project” (1985-1993), a collaboration with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, which includes two stained-glass windows and a tapestry; and “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction” (2015-2019), a body of work that explores mortality and environmental crisis through the painstaking medium of glass painting. The Dinner Party will not travel from Brooklyn but will be well represented by drawings, films, sculptures and test plates.

The museum has even commissioned one of Chicago’s signature smoke sculptures — pyrotechnic displays that emerged out of the artist’s interest in the emotional resonance of color and the desire to feminize her male surrounds — which will be performed Aug. 15 at dusk on the music concourse between the de Young and the Academy of Science. Rainbow plumes of smoke will cascade down one of two staircases, swirl around a central fountain and appear to crawl up the other set of stairs.

Chicago will be honored by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco on March 27, at the inaugural On The Edge benefit. Taking place on the eve of the de Young’s 125th anniversary, the event will also pay tribute to landscape designer Walter Hood and technologist John Maeda. This is just the latest among Chicago’s several recent accolades, including in 2018 being named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People and one of Artsy’s Most Influential Artists. And this past winter she was recognized by the fashion world: Maria Grazia Chiuri, the creative director of Dior, invited the artist to create a 225-foot-long inflatable anthropomorphic “goddess” structure on the grounds of Paris’s Musée Rodin to show the house’s Spring/Summer 2020 couture show. Chicago, with her signature purple-dyed locks, attended the show in a custom gold Dior suit.

Throughout her career, change has perhaps been the only constant for Chicago, who utilizes whatever medium fits her needs — from painting to sculpture, textiles to film, ceramics to performance. Born Judy Cohen in Chicago in 1939, she changed her name twice: to Gerowitz after her first marriage and then to Chicago in the mid-’60s as a declaration of independence and rebirth. After she graduated from UCLA, her early works, such as minimalist constructions and automotive lacquer paintings on car hoods, showed a connection to other Angeleno artists associated with the Light and Space movement, before she switched to more feminist modes of art-making. Schmuckli explains, “She established herself within the L.A. art scene, first by trying to fit into the boys club, and finally recognizing she wanted to come into her own and have her own voice.”

“I have pursued an artistic quest that involves making the female experience a pathway to the universal”

Judy Chicago

Much of Chicago’s work has a politically progressive stance, but she points out that her creativity is not in service of any particular political or aesthetic agenda. (Though the retrospective purposely coincides with the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women suffrage.)

“Art has no responsibilities. Only artists have responsibilities, and the beauty of art is that each artist gets to define what responsibilities they wish to tackle,” Chicago says. “Some artists want to be concerned only about the formal properties of art-making. That is their right, though for me, it accounts for a lot of boring art. Other artists see the potential power of art as a way to make political statements.”

Certainly no one can accuse Chicago of making boring art. “I have eschewed both these paths as I have pursued an artistic quest that involves making the female experience a pathway to the universal, in the same way the male experience has been,” she says. “This has led me to tackle subjects of human significance, like whose history is important; birth and death; the construct of gender, both feminine and masculine; our capacity for evil, as in ‘Holocaust Project’; our potential for a better future, as in ‘Resolutions’; and our relationship with other species — playfully, as in ‘Kitty City’; and more seriously, [as] in my recent project ‘The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction.’”

When her retrospective opens this spring, audiences will get a chance to see the full breadth of her artistic quest, an unveiling that has been a long time coming. “For so many decades, my body of art was obscured by the shadow of The Dinner Party and the intense resistance of the art world,” Chicago explains. “Many people remarked that the 2018 show at [the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami] surveying three decades of my career was a ‘revelation.’ My hope is that as people can see more of my work, they will continue to feel that way, as my lifelong goal has always been to make a contribution to art history.”

Feature image: As the title of “On Fire at 80” (2019) asserts, artist JUDY CHICAGO isn’t cooling down. Photo by Donald Woodman/ARS, New York.

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of C Magazine.

Discover more CULTURE news.