With its remote location and modernist rule book, we look back at what keeps design pilgrims coming back

Introduction by MELISSA GOLDSTEIN

Like Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú home in Santa Fe, or Donald Judd’s compound The Block in Marfa, the planned community north of San Francisco known as The Sea Ranch is more than a design destination: it’s a mecca for modernist pilgrims.

The story of how the 5,000 acres of rugged coastal Sonoma County land on which The Sea Ranch sits came to be a cult architectural attraction begins in 1964—when Oceanic Properties, a subsidiary of a Hawaiian real estate developer, purchased the unspoiled property from a sheep-ranching family.

Architect Al Boeke was at the helm of what would become a pioneering study in ecological planning, and he recruited an A-list cast to create an idealistic community where people would happily sacrifice such suburban staples as streetlights, lawns and anything-but-neutral drapes to inhabit a 10-mile stretch of land where nature would be front and center.

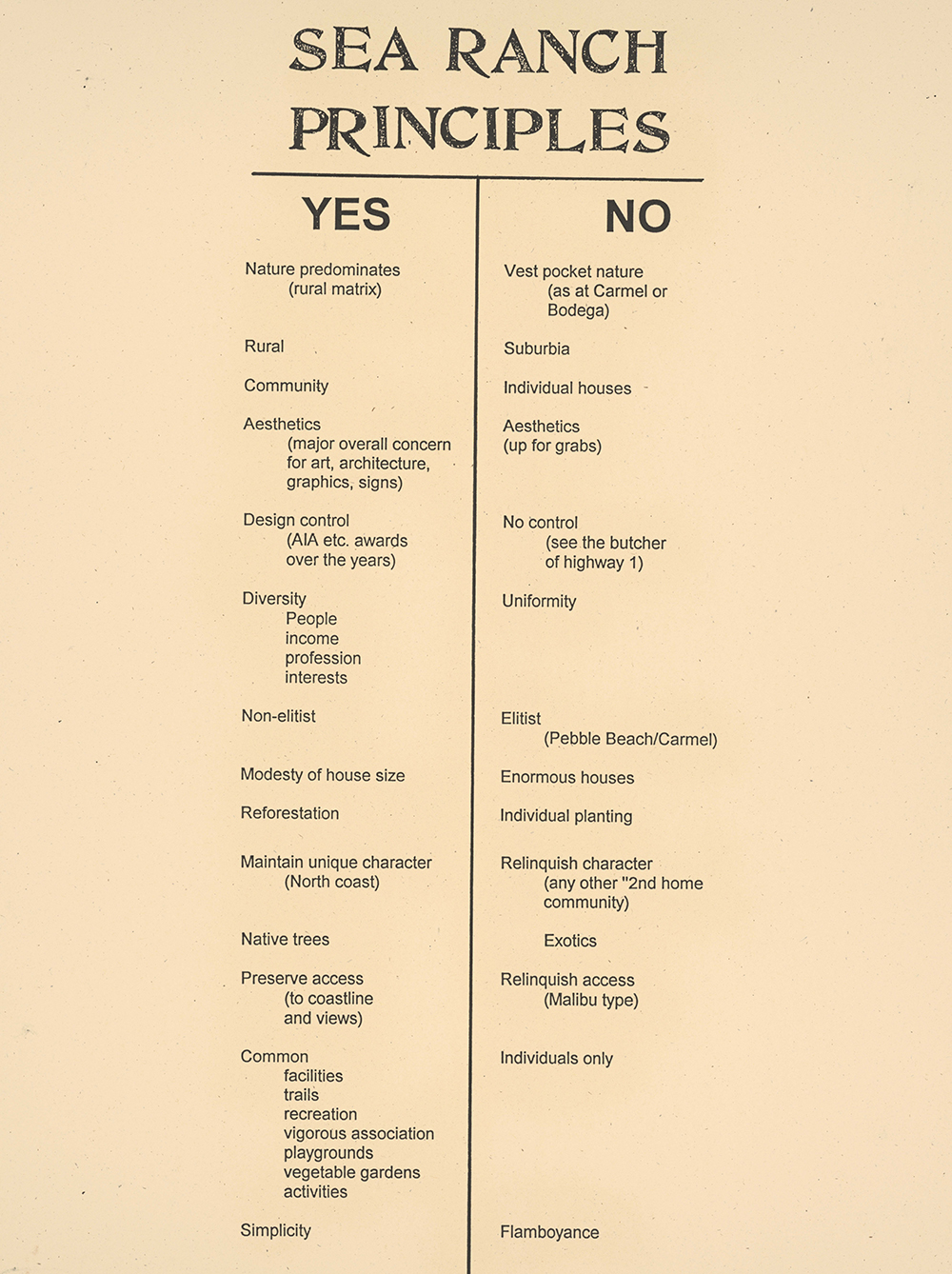

Landscape designer Lawrence Halprin worked with architectural firm Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull and Whitaker and architect Joseph Esherick to conceptualize the development, governed by a sacred set of design principles providing for, among other things, uninterrupted views of the sea and abundant communal space. Every detail of the timber-clad redwood residences, from the angled plank roofs to the slanted towers, was chosen to coexist in harmony with the elements.

From its inception, The Sea Ranch appealed to conservation-minded people who relished a challenge, prized a thoughtful life over a convenient one, and enthusiastically signed The Sea Ranch “covenant,” promising to preserve the place’s character for the present and future in all of their actions. Having influenced legions of progressive architects, The Sea Ranch is now the subject of a new exhibition at SFMOMA (“The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism,” Dec. 22, 2018-Apr. 28, 2019) co-curated by Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher and Joseph Becker, who also co-edited a companion title by the same name, featuring archival and modern-day images as well as the development’s iconic graphics (designed by Barbara Stauffacher Solomon) while exploring its lasting legacy. Here, we excerpt an essay by Becker, in which he examines the enclave’s beginnings and its enduring appeal.

*******

“The California architectural monument of the 1960s”— so the architectural historian David Gebhard described The Sea Ranch’s Condominium One some twenty years after its construction. From its founding, The Sea Ranch captured the attention of the local and international architecture world, through featured articles in Progressive Architecture and Global Architecture—and beyond, in newspapers and publications like Newsweek—not only for the irrefutable allure of its dramatic coastal location or its pioneering use of graphics. More importantly, it was heralded for its unique approach to its site and careful attention to materials, informed by progressive ideals uniquely rooted in Bay Area history and a sensitivity toward both social and environmental concerns. In 1965, with only a handful of structures completed on a development site intended to hold thousands, the architecture of The Sea Ranch signaled a new era in building that attempted to hold emerging countercultural impulses and developer-driven financial imperatives in a sympathetic balance. So transformative was this initial phase of The Sea Ranch development that it set off a wave of inspiration in form and typology, radiating well beyond Northern California, and set in place a system for the sensitive occupation of a precious landscape that acknowledged the past while operating from a distinctly modern perspective…

…Flying over the Pacific line in 1962, Al Boeke was struck by the beauty of the land. He had been looking for a site with “identity,” and found it in a unique combination of location and terrain, from the ocean cliffs and flat bluffs to the redwood ridges and Gualala River. Operating as a developer, his intentions of building on the site were clear, but given his background as a practicing architect, he was also attentive to the impact that the development would have on the landscape. Boeke saw an opportunity to combine the Bay Area’s history of responsiveness and respect for landscape conditions with a modern agenda, including the development of a new condominium typology that would increase housing density while preserving open space. Crucially, Boeke’s foresight was in assembling an ideal team to contribute to the overall project.

Boeke had worked for Neutra on Mililani Town in Hawaii and was profoundly aware that architecture’s success depended upon synergy between building and site. Key among the collaborators he brought together to realize this vision was the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, who had worked with Boeke in Los Angeles. Halprin had studied under Gropius at Harvard University, and yet the core tenets of International Style modernism he had absorbed there gave way to an approach inspired by a visit to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin studio in Wisconsin. Halprin directed his practice toward analyzing regional tactics and material contexts and developing an ecologically driven, holistic vision. In negotiating these concerns, he established a master plan with Boeke, which included hiring a group of consultants from an “unprecedented wide range of disciplines: foresters, grassland advisors, engineers, attorneys, hydrologists, climatologists, geologists, geographers, demographers, graphic artists, public relations and marketing people,” to gain a full understanding of the site and to determine how it would be represented to the public.

The Sea Ranch embodied a vision of progress that was in dialogue with the long history of its site. The early phases were marked by graphic representations of both, from Larry Halprin’s Ecoscore, which charted the land along a timeline of human, geological, and biological history, to Barbara “Bobbie” Stauffacher Solomon’s Swiss rational graphic design for the logo and related graphic materials set in the cleanly modern Helvetica typeface that Solomon had brought back to California from her time in Basel with Armin Hofmann.

The wide-ranging influence of The Sea Ranch launched a new era of Bay Area architecture, with increased recognition of its contributions to a particular aesthetic and to a richer philosophy of “place making.” As Moore and Lyndon observed: “A house is in delicate balance with its surroundings, and they with it.” The Sea Ranch represented not only this distinctive aesthetic, it also blended social interest and ecological sensitivity. From its origins in the architectural history of Bay Area regionalism and extant vernacular structures came a synthesis with emerging issues of modernism and progressive ideals for how to occupy a landscape. The early phase of The Sea Ranch aimed to lay the groundwork for a new community in partnership with a physically and visually dominant setting. The new frontierism and lonely taming of a majestic coast as represented in the marketing photographs called to a free-spirited generation to sublimely settle in uncharted land. And crucially, it was the manifestation of that vision, the placement of these structures in reverence to the much larger scheme of Halprin’s Sea Ranch Ecoscore, that earned it so many early accolades and made good on Mumford’s pledge of “that native and humane form of modernism which one might call the Bay Region style, a free yet unobtrusive expression of the terrain, the climate, and the way of life on the Coast.”

A version of this essay was published as “Building in Place” in The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and DelMonico Books-Prestel, 2019), edited by Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher and Joseph Becker.

This story originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of C magazine.